Developers pursuing higher-dollar rehabs of historic buildings will be limited this year in the amount of state tax credits they can receive for their projects, according to legislation making its way through the General Assembly.

The House and Senate have passed bills that would cap the amount of credit a taxpayer can claim through the state’s historic rehabilitation tax credit program at $5 million per year, though an amendment approved Friday to one of the bills limits that change to the 2017 calendar year.

House Bill 2460, which includes the amendment, passed the Senate Friday by a vote of 29-9 with one abstention. The bill without the amendment passed the House the previous week.

An identical bill in the Senate, SB1034, appears to be following a similar course, referred last Wednesday to the House finance committee after the Senate passed it unanimously the previous week.

The two bills must be signed by the governor to become law.

The one-year provision added to HB2460 was fought for by a coalition led by the Home Building Association of Richmond (HBAR). Other groups involved include Preservation Virginia, the Virginia Bankers Association, Virginia Association of Realtors, Virginia Association for Commercial Real Estate and the Southern Environmental Law Center.

Andrew Clark, government affairs director for HBAR, said the coalition has been working with House legislators to have a similar one-year restriction added to SB1034. He said that bill is scheduled to be heard this morning (Monday).

Clark said the coalition has been working since last summer to educate legislators on the program and its impact on the state, not only in urban centers but also counties. He said if legislators went forward with the $5 million per-taxpayer cap, the coalition sought to limit the change to one year to allow for further studies and discussion on the program.

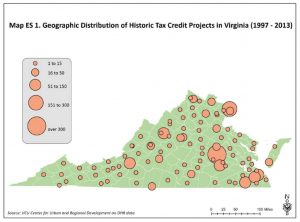

A 2014 study commissioned by Preservation Virginia and conducted by the VCU Center for Urban and Regional Analysis found that over the program’s first 17 years, from 1997 to 2013, there were 2,375 historic rehab tax credit projects across Virginia totaling just under $4 billion. Of that amount, nearly $1 billion was invested by property owners and developers in historic rehabs in lieu of taxes, which in turn stimulated nearly $3 billion in additional private investment.

The study also showed those projects created more than 31,000 full- and part-time jobs, and that the credits were used for projects in 80 counties as well as the state’s 11 metropolitan statistical areas.

“The financing provided through the state’s historic tax credit program is vital to making these projects possible,” Clark said. “Uncertainty around the future of the program will have a chilling effect on economic development projects across the commonwealth.

“These are extremely complex and costly projects that would otherwise stay dormant,” he said. “The state historic tax credit program has been the driving force behind the revitalization of key corridors and neighborhoods across Richmond.”

Currently, the state credits are awarded through the Department of Historic Resources as dollar-for-dollar reductions in income tax liability for taxpayers rehabbing historic buildings. Federal credits are also available and would not be changed by the state legislation.

Both credits are based on total rehab project costs. The state credit is 25 percent of eligible project expenses, while the federal credit is 20 percent.

Elizabeth Kostelny, CEO of Preservation Virginia, a Richmond-based nonprofit, said groups they’ve worked with in the coalition are not so much opposed to a cap on the credit as taking such an action this legislative session. She said the additional time would allow for studies on the impact such a cap would have on the state.

“We think it would be more prudent to study the impact of any kind of amendments to the program and understand that before starting to amend the program,” Kostelny said. Without the ability to revisit the issue in a year, she said the changes to the program add uncertainty in the long-term.

“The uncertainty comes from the investor standpoint: Is this going to be the same program that they’re investing in today? Will it be the same program when they need to use the tax credits, because there are all these questions about it,” she said.

Such questions recently prompted Richmond-based developer The Monument Cos. to pull out of a $30 million mixed-use project in Suffolk. The project, as reported last month by the Suffolk News-Herald, was planned to rehabilitate a 10-acre, 17-building industrial site that was previously home to the Golden Peanut company.

Monument principal Tom Dickey said the company pulled the project because it relied on the credits and would have taken at least five years to complete.

“There is already enough uncertainty in the world, and not knowing (if) the project (would) be eligible for credits as we entered the final phases made us very nervous,” Dickey said in an email. “Projects such as the Golden Peanut in Suffolk, and other smaller cities such as Petersburg, Danville and Staunton, are already pretty tight even with the tax credit incentives. I don’t think you could justify any of them without the program, even if you were given the building for free.”

The bills are but the latest proposals in recent years to limit or phase out the program and similar state tax credits. An identical bill, HB1635, was killed in committee in January, as was legislation proposed by Sen. Glen Sturtevant of Richmond that would have capped and phased out the program and two other state credits.

Sturtevant has said the historic rehab tax credit program cost the state $98 million in tax revenue in 2016 – a year that saw a state budget shortfall defer promised raises for public employees.

According to the Department of Historic Resources, Virginia saw 439 historic rehab tax credit projects from 2013-15, the most recent data available. Those projects totaled $1 billion in investment in the state.

In the city of Richmond, which leads the state in historic rehab tax credit projects, the same period saw 247 projects totaling $447.89 million in investment. In 2013, the city saw 157 projects totaling $251 million; in 2014, 158 projects totaling $492 million; and in 2015, 124 projects totaling $292 million.

Monument Cos. principal Chris Johnson said changes to the program could require the company to focus on other fields, and turn its attention to projects in other states.

“If state historic tax credits were to go away, we would obviously turn our focus more sharply to new construction, likely urban infill, locally,” Johnson said. “We have spent a good portion of our careers building up the necessary expertise and team to tackle historic tax credit projects, and would not want to abandon that market.

“More than likely we would shift that part of our business to other states, most likely Texas, which has just recently implemented a state historic tax credit program that has similar benefits as Virginia,” he said.

Developers pursuing higher-dollar rehabs of historic buildings will be limited this year in the amount of state tax credits they can receive for their projects, according to legislation making its way through the General Assembly.

The House and Senate have passed bills that would cap the amount of credit a taxpayer can claim through the state’s historic rehabilitation tax credit program at $5 million per year, though an amendment approved Friday to one of the bills limits that change to the 2017 calendar year.

House Bill 2460, which includes the amendment, passed the Senate Friday by a vote of 29-9 with one abstention. The bill without the amendment passed the House the previous week.

An identical bill in the Senate, SB1034, appears to be following a similar course, referred last Wednesday to the House finance committee after the Senate passed it unanimously the previous week.

The two bills must be signed by the governor to become law.

The one-year provision added to HB2460 was fought for by a coalition led by the Home Building Association of Richmond (HBAR). Other groups involved include Preservation Virginia, the Virginia Bankers Association, Virginia Association of Realtors, Virginia Association for Commercial Real Estate and the Southern Environmental Law Center.

Andrew Clark, government affairs director for HBAR, said the coalition has been working with House legislators to have a similar one-year restriction added to SB1034. He said that bill is scheduled to be heard this morning (Monday).

Clark said the coalition has been working since last summer to educate legislators on the program and its impact on the state, not only in urban centers but also counties. He said if legislators went forward with the $5 million per-taxpayer cap, the coalition sought to limit the change to one year to allow for further studies and discussion on the program.

A 2014 study commissioned by Preservation Virginia and conducted by the VCU Center for Urban and Regional Analysis found that over the program’s first 17 years, from 1997 to 2013, there were 2,375 historic rehab tax credit projects across Virginia totaling just under $4 billion. Of that amount, nearly $1 billion was invested by property owners and developers in historic rehabs in lieu of taxes, which in turn stimulated nearly $3 billion in additional private investment.

The study also showed those projects created more than 31,000 full- and part-time jobs, and that the credits were used for projects in 80 counties as well as the state’s 11 metropolitan statistical areas.

“The financing provided through the state’s historic tax credit program is vital to making these projects possible,” Clark said. “Uncertainty around the future of the program will have a chilling effect on economic development projects across the commonwealth.

“These are extremely complex and costly projects that would otherwise stay dormant,” he said. “The state historic tax credit program has been the driving force behind the revitalization of key corridors and neighborhoods across Richmond.”

Currently, the state credits are awarded through the Department of Historic Resources as dollar-for-dollar reductions in income tax liability for taxpayers rehabbing historic buildings. Federal credits are also available and would not be changed by the state legislation.

Both credits are based on total rehab project costs. The state credit is 25 percent of eligible project expenses, while the federal credit is 20 percent.

Elizabeth Kostelny, CEO of Preservation Virginia, a Richmond-based nonprofit, said groups they’ve worked with in the coalition are not so much opposed to a cap on the credit as taking such an action this legislative session. She said the additional time would allow for studies on the impact such a cap would have on the state.

“We think it would be more prudent to study the impact of any kind of amendments to the program and understand that before starting to amend the program,” Kostelny said. Without the ability to revisit the issue in a year, she said the changes to the program add uncertainty in the long-term.

“The uncertainty comes from the investor standpoint: Is this going to be the same program that they’re investing in today? Will it be the same program when they need to use the tax credits, because there are all these questions about it,” she said.

Such questions recently prompted Richmond-based developer The Monument Cos. to pull out of a $30 million mixed-use project in Suffolk. The project, as reported last month by the Suffolk News-Herald, was planned to rehabilitate a 10-acre, 17-building industrial site that was previously home to the Golden Peanut company.

Monument principal Tom Dickey said the company pulled the project because it relied on the credits and would have taken at least five years to complete.

“There is already enough uncertainty in the world, and not knowing (if) the project (would) be eligible for credits as we entered the final phases made us very nervous,” Dickey said in an email. “Projects such as the Golden Peanut in Suffolk, and other smaller cities such as Petersburg, Danville and Staunton, are already pretty tight even with the tax credit incentives. I don’t think you could justify any of them without the program, even if you were given the building for free.”

The bills are but the latest proposals in recent years to limit or phase out the program and similar state tax credits. An identical bill, HB1635, was killed in committee in January, as was legislation proposed by Sen. Glen Sturtevant of Richmond that would have capped and phased out the program and two other state credits.

Sturtevant has said the historic rehab tax credit program cost the state $98 million in tax revenue in 2016 – a year that saw a state budget shortfall defer promised raises for public employees.

According to the Department of Historic Resources, Virginia saw 439 historic rehab tax credit projects from 2013-15, the most recent data available. Those projects totaled $1 billion in investment in the state.

In the city of Richmond, which leads the state in historic rehab tax credit projects, the same period saw 247 projects totaling $447.89 million in investment. In 2013, the city saw 157 projects totaling $251 million; in 2014, 158 projects totaling $492 million; and in 2015, 124 projects totaling $292 million.

Monument Cos. principal Chris Johnson said changes to the program could require the company to focus on other fields, and turn its attention to projects in other states.

“If state historic tax credits were to go away, we would obviously turn our focus more sharply to new construction, likely urban infill, locally,” Johnson said. “We have spent a good portion of our careers building up the necessary expertise and team to tackle historic tax credit projects, and would not want to abandon that market.

“More than likely we would shift that part of our business to other states, most likely Texas, which has just recently implemented a state historic tax credit program that has similar benefits as Virginia,” he said.

When the politicians find that the private sector can make something work for the good of the public, they immediately begin the process of taxing and regulating it until that program fails. Sturdevants assertion that it costs tax payers money is born of ignorance. I thought he was smarter than that

I can’t believe they wouldn’t phase something in if this passes. They at least should make it effective starting in 2018 so that current construction in progress projects are not crushed.

Just to clarify- the House and Senate bills would place a $5M cap on the amount of historic tax credits that a taxpayer can claim at the end of the year. They do not cap the amount of tax credits that a developer can receive and they do not cap the amount of tax credits that can be allocated by DHR in a given year.

If that is the case, then only individuals or corporations with over $100,000,000 in AGI would hit the limit. Seems like there are still a few folks making less that will buy the credits….? Or is there more information missing from this article?

This article does not clarify what is being limited: Is it the amount of $$ in credits an entity may create by developing a historic project, or the amount of $$ in credits an individual/entity may use to pay down their tax?

These government incentives to foster private-industry investment clearly is producing state revenue. The numbers prove it. W/ out these incentives and stimulus there will be even less state revenue. Spend a dollar-Virginia. Don’t hurt deveopment in Virginia by destroying these programs!

These government incentives to foster private-industry investment clearly are producing state revenue. The numbers prove it. W/ out these incentives and stimulus there will be even less state revenue. Spend a dollar-Virginia. Don’t hurt deveopment in Virginia by destroying these programs!

These historic tax-incentive programs are generating millions of dollars of construction improvements in the Commonwealth. And the numbers prove the program is paying for itself and creating a great return on investment for the state. Why cap or even end these incentives?

The state will end up w/ even less revenue to pay teachers. Virginia spend a dime earn a dollar Use common fiscal sense.,

So the raw numbers show that a “cost” to the state of $1billion, they received $3billion in hard investment. Hmmmmm . . . That certainly seems like something worthwhile to phase out. How do we elect these people?!!

I cannot believe our elected representatives cannot perceive the tremendous stimulus Virginia’s current Historic rehabilitation tax credit program has provided to our economy—not to mention the long-term tax benefits generated via the increased real estate taxes that will be collected by Virginia Cities and Counties from the rehabilitated structures that might otherwise have been torn down or left derelict.

Perhaps they don’t realize that much of the construction they drive/walk past on their way to work in the General Assembly probably wouldn’t exist were it not for the financial incentives now offered in Virginia.

I don’t get it.

Hmmm, I’m sure it has nothing to do with the main business his opponent in the last election is involved with. In any case, he might want to visit the more urban parts of his district in Richmond that have benefitted from these types of projects. Perhaps some of the historic preservation activists might be able to supply him a list of all the structures rehabbed in his district over the years.