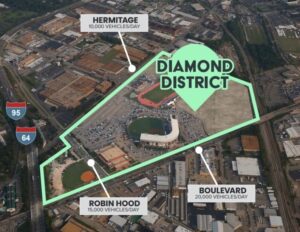

The future CarMax Park that will replace The Diamond and is to anchor the 67-acre Diamond District development. (Image courtesy Richmond Flying Squirrels)

Editor’s note: This is Part 1 of a two-part series.

“If I sound stressed about this, it is because I am. It’s Thursday, February 16. LFG.”

That was the urgency with which Todd “Parney” Parnell, then the VP and COO of the Richmond Flying Squirrels, ended an email to a group of developers and designers who were working on initial plans for the new baseball stadium to replace the ballclub’s aging home of over a decade, The Diamond.

Responding to an email titled “Napkin Numbers” – a reference to notes he’d jotted down during a call two days earlier – Parnell emphasized the timeframe that the group was facing to deliver a new ballpark by Opening Day 2025, the deadline that Major League Baseball had set for all pro baseball venues to meet required facilities standards.

In his reply, Parnell told the group: “We really need you guys to move forward with your development deal so we can really get down to business. We are running out of time on the baseball side and I am becoming…increasingly scared but I don’t control your deal only the developer and the city does.

“So please. Get it done. We need progress and we need it now,” Parnell wrote, ending his message with “LFG” – an acronym for “Let’s freaking go,” or a more colorful version.

That was early 2023.

Final terms for a deal between the City of Richmond and its selected development team at the time, RVA Diamond Partners, would be reached three months later. But the lead developer on that team, D.C.-based Republic Properties, refused to sign off on the deal and withdrew from the project, according to filings in a $40 million lawsuit from Republic that now hangs over the larger Diamond District project – the 67-acre development that the new ballpark is to anchor.

A year later, days before City Council this past May OK’d a reworked deal with Diamond District Partners – a new group led by Republic’s former teammates Loop Capital and Thalhimer Realty Partners – Republic principal Jordan Kramer emailed Lincoln Saunders, Richmond’s chief administrative officer, requesting a call with Republic’s legal counsel “to discuss a settlement.”

Saunders replied asking what there was for them to discuss. “The City terminated its negotiations with (RVA Diamond Partners) and Republic a year ago,” Saunders said.

“As you know,” Kramer responded, “there are differences that need to be bridged between Republic and Thalhimer/Loop to resolve our relationship and the relationship between our partnership and the City. We see the City as a part of any resolution.”

“That doesn’t provide any clarity,” Saunders replied. “There is no existing partnership between Republic and the City.”

The email exchanges bookend the final 15 months of a two-and-a-half-year, at-times tumultuous process to find consensus in the design and nail down a development deal for the new ballpark – now to be named CarMax Park – that had been promised to the Flying Squirrels since the team arrived in Richmond 15 years ago.

Emails obtained by Richmond BizSense through Freedom of Information Act requests to the city reveal how contentious that process became, how the project was reworked and salvaged over that time, and how it came to be that Republic – and later Loop – stepped away from the $2.4 billion public-private project they had won with Thalhimer over 14 other development teams that competed for it.

This report was compiled from those emails, court filings from the lawsuit, and BizSense’s reporting.

‘Little progress on plans’

The Flying Squirrels’ Todd ‘Parney’ Parnell addressing attendees at the development team announcement for the Diamond District project in September 2022. (BizSense file photos)

By the time Parnell sent his “Napkin Numbers” email, RVA Diamond Partners was months into the process that started in fall 2022 with a design charette involving Flying Squirrels staff and VCU Athletics, whose Division I baseball team shares the minor-league ballclub’s facilities.

Also involved in the charette were DLR Group and JMI Sports – RVA Diamond Partners’ stadium designer and development consultant, respectively. DLR’s minor-league credits had included Fluor Field stadium in Greenville, South Carolina, and JMI had worked on Chase Center in San Francisco and Petco Park, home to MLB’s San Diego Padres.

But as the process played out over months, with the ballpark being shaped based on the Squirrels’ feedback and within the confines of an originally $80 million projected budget, Squirrels leadership became frustrated with how the process was going in light of MLB’s spring 2025 deadline, which left just enough time for what developers said would need to be at least an 18-month build.

The ballclub’s dissatisfaction was aired publicly in April of last year, when president and managing general partner Lou DiBella put out a statement saying there had been “little progress on plans for a new stadium” and that the club “cannot be confident that the future of the Squirrels in Richmond is secure.”

At the same time, Squirrels leadership had warmed to and stayed connected with David Carlock, principal of Houston-based Machete Group, which had led the runner-up development team that lost out to RVA Diamond Partners. That team had included architecture firm Odell (now LaBella Associates), which designed the minor-league BB&T Ballpark in Charlotte.

DiBella’s statement frustrated city officials and Jason Guillot, the Thalhimer principal who was RVA Diamond Partners’ local lead on the Diamond District.

While setting up a group meeting two weeks after DiBella’s statement, Guillot asked Carlock in an email: “How do we keep all the parties focused to make some progress? I don’t believe that airing our dirty laundry in the press helps us close a deal.”

In another email the same day to Jonathan Fine, an attorney and sports industry advisor for the city, Guillot said he believed that, “after many months, I’ve finally earned some trust by Lou, Larry and Parney,” referring to DiBella, Squirrels co-owner Larry Botel, and Parnell.

However, Guillot added: “I do believe their public display is not fair to the City and to us given how much time we have invested with them to get to this point.”

In the following weeks, the parties held a group call with MLB-owned Minor League Baseball and met with stadium designer DLR during a ChamberRVA-led trip to Kansas City, Missouri, where Guillot, Carlock, Parnell and others toured the stadium for MLB’s Kansas City Royals.

But Guillot’s hopes of having earned DiBella’s trust were soon dashed – as Guillot relayed in an email to Fine, Richmond CAO Saunders and Leonard Sledge, the city’s then-economic development director.

Describing a call he had with DiBella the previous day – the same day that City Council approved the initial development deal with RVA Diamond Partners – Guillot wrote that DiBella had said “that he should have objected more to our team getting selected by the City and that I’m no friend of his.”

“I told him while I don’t expect to win his friendship, we do need to work together productively and that negative quotes in the media by him undermines our ability to convince bond investors that we have an exceptional project and that we’re all rowing in the same direction,” Guillot wrote, adding: “perception matters.”

“He of course took great offense at this and claims he’s not said anything untrue. As we wrapped up the call, he said he should just sell the team because the hassle isn’t worth it,” Guillot wrote. “I asked him what his price is because I might be able to pull together an investor group to take him out. Of course, he said he wants to wait for the new ballpark to be built…”

‘We still have a lot of trust to rebuild’

Site work started this fall on CarMax Park, which will replace the adjacent, nearly 40-year-old Diamond. (Skyshots Photography)

As tensions were growing between the developers and the Squirrels, they’d also grown between the city and Republic, the lead developer on RVA Diamond Partners that had brought locally based Thalhimer and Chicago-based Loop into the fold.

In early April 2023, a week before DiBella made his frustrations public, Republic sent the city a list of issues with the project that it wanted addressed before it would sign off on a formal development deal. One of those issues was whether the ballpark budget, which by that point had grown to over $90 million, was not sufficient to the city.

A gulf had formed between the parties over the desired capacity and cost of the ballpark, which RVA Diamond Partners had been planning as a 9,000-seat stadium. The Squirrels were insisting on a 10,000-capacity venue – a change that, among others, would ultimately push the ballpark’s cost to over $117 million.

In an email to Republic later that month, Saunders, the CAO, said the city had proposed a financing plan for the stadium, “sized in a manner that we believe is appropriate for the City, that further reduces the financial risk for RVADP while increasing the financial risk for the City.”

Later, while insisting on a meeting with the developers the next day, Saunders added in that email: “We still have a lot of trust to rebuild to get back to a position of feeling comfortable with moving forward with this partnership. Hearing your response tomorrow will be critical to knowing whether we should continue working to reach agreement.”

A deal with RVA Diamond Partners would ultimately be reached. But, soon after the development agreement was approved by City Council, Republic notified Thalhimer that it was exiting the project and “confirmed in writing that it would not continue to participate in the development,” Thalhimer has said.

Republic also notified the city that it had made an offer to Thalhimer and Loop “that would remove us from RVA Diamond Partners and enable them to move forward with the development of the Diamond District,” Republic’s Jordan Kramer said in a May 2023 email to Richmond’s Saunders and Sledge.

“If accepted, Republic would no longer be party to the teaming or operating agreements,” said Kramer, son of Republic board chairman Richard Kramer. “We are waiting to see if Loop and Thalhimer agree to our terms but until we get a firm answer, there’s nothing else we can do at this time.”

Republic had previously told the city that it would deliver by the day of Kramer’s email an operating agreement and governance documents for RVA Diamond Partners, which the three companies were restructuring. The LLC had been structured, according to Republic’s lawsuit, with Republic and Loop each owning 40% and Thalhimer owning 20%.

In a prior email to a lawyer for RVA Diamond Partners, John O’Neill – an attorney with Hunton Andrews Kurth, the city’s outside legal counsel – said the group had “reported that meaningful progress was being made in (the) LLC’s restructuring” and “conversations with additional equity participants were advancing…,” but that Thalhimer had since informed the city that “restructuring progress has stalled.”

With no documents delivered by the date they’d said they would be, Saunders, the city CAO, sent the three companies an email terminating their negotiations on the Diamond District.

“This notification of the consequences of (RVA Diamond Partners’) failure to make such delivery followed the prior failure of RVADP to (1) deliver such governance documents with the terms the City required and (2) execute and deliver the Development Agreement and Purchase and Sale Agreement in a timely manner…” Saunders’ email said.

“We are very disappointed that this action is occurring. But after months of negotiations with RVADP after its selection as the preferred proposer for the Diamond District project…the City can wait no longer for RVADP to resolve whatever internal issues it is facing and risk losing its ability to timely undertake this critical economic development priority.”

The timing of the ballpark had become more urgent in light of MLB’s deadline for all pro baseball venues to meet new facility standards by Opening Day 2025. Months before Saunders’ email, MLB had required $3 million in upgrades to The Diamond that the city had to spend to keep the Squirrels playing there in the meantime.

By the time final terms for the original development deal had been reached, however, officials acknowledged that the ballpark would not meet the 2025 deadline and started aiming instead for spring 2026 – an extension that MLB has appeared to allow.

Look for Part 2 of this story in tomorrow’s BizSense.

The future CarMax Park that will replace The Diamond and is to anchor the 67-acre Diamond District development. (Image courtesy Richmond Flying Squirrels)

Editor’s note: This is Part 1 of a two-part series.

“If I sound stressed about this, it is because I am. It’s Thursday, February 16. LFG.”

That was the urgency with which Todd “Parney” Parnell, then the VP and COO of the Richmond Flying Squirrels, ended an email to a group of developers and designers who were working on initial plans for the new baseball stadium to replace the ballclub’s aging home of over a decade, The Diamond.

Responding to an email titled “Napkin Numbers” – a reference to notes he’d jotted down during a call two days earlier – Parnell emphasized the timeframe that the group was facing to deliver a new ballpark by Opening Day 2025, the deadline that Major League Baseball had set for all pro baseball venues to meet required facilities standards.

In his reply, Parnell told the group: “We really need you guys to move forward with your development deal so we can really get down to business. We are running out of time on the baseball side and I am becoming…increasingly scared but I don’t control your deal only the developer and the city does.

“So please. Get it done. We need progress and we need it now,” Parnell wrote, ending his message with “LFG” – an acronym for “Let’s freaking go,” or a more colorful version.

That was early 2023.

Final terms for a deal between the City of Richmond and its selected development team at the time, RVA Diamond Partners, would be reached three months later. But the lead developer on that team, D.C.-based Republic Properties, refused to sign off on the deal and withdrew from the project, according to filings in a $40 million lawsuit from Republic that now hangs over the larger Diamond District project – the 67-acre development that the new ballpark is to anchor.

A year later, days before City Council this past May OK’d a reworked deal with Diamond District Partners – a new group led by Republic’s former teammates Loop Capital and Thalhimer Realty Partners – Republic principal Jordan Kramer emailed Lincoln Saunders, Richmond’s chief administrative officer, requesting a call with Republic’s legal counsel “to discuss a settlement.”

Saunders replied asking what there was for them to discuss. “The City terminated its negotiations with (RVA Diamond Partners) and Republic a year ago,” Saunders said.

“As you know,” Kramer responded, “there are differences that need to be bridged between Republic and Thalhimer/Loop to resolve our relationship and the relationship between our partnership and the City. We see the City as a part of any resolution.”

“That doesn’t provide any clarity,” Saunders replied. “There is no existing partnership between Republic and the City.”

The email exchanges bookend the final 15 months of a two-and-a-half-year, at-times tumultuous process to find consensus in the design and nail down a development deal for the new ballpark – now to be named CarMax Park – that had been promised to the Flying Squirrels since the team arrived in Richmond 15 years ago.

Emails obtained by Richmond BizSense through Freedom of Information Act requests to the city reveal how contentious that process became, how the project was reworked and salvaged over that time, and how it came to be that Republic – and later Loop – stepped away from the $2.4 billion public-private project they had won with Thalhimer over 14 other development teams that competed for it.

This report was compiled from those emails, court filings from the lawsuit, and BizSense’s reporting.

‘Little progress on plans’

The Flying Squirrels’ Todd ‘Parney’ Parnell addressing attendees at the development team announcement for the Diamond District project in September 2022. (BizSense file photos)

By the time Parnell sent his “Napkin Numbers” email, RVA Diamond Partners was months into the process that started in fall 2022 with a design charette involving Flying Squirrels staff and VCU Athletics, whose Division I baseball team shares the minor-league ballclub’s facilities.

Also involved in the charette were DLR Group and JMI Sports – RVA Diamond Partners’ stadium designer and development consultant, respectively. DLR’s minor-league credits had included Fluor Field stadium in Greenville, South Carolina, and JMI had worked on Chase Center in San Francisco and Petco Park, home to MLB’s San Diego Padres.

But as the process played out over months, with the ballpark being shaped based on the Squirrels’ feedback and within the confines of an originally $80 million projected budget, Squirrels leadership became frustrated with how the process was going in light of MLB’s spring 2025 deadline, which left just enough time for what developers said would need to be at least an 18-month build.

The ballclub’s dissatisfaction was aired publicly in April of last year, when president and managing general partner Lou DiBella put out a statement saying there had been “little progress on plans for a new stadium” and that the club “cannot be confident that the future of the Squirrels in Richmond is secure.”

At the same time, Squirrels leadership had warmed to and stayed connected with David Carlock, principal of Houston-based Machete Group, which had led the runner-up development team that lost out to RVA Diamond Partners. That team had included architecture firm Odell (now LaBella Associates), which designed the minor-league BB&T Ballpark in Charlotte.

DiBella’s statement frustrated city officials and Jason Guillot, the Thalhimer principal who was RVA Diamond Partners’ local lead on the Diamond District.

While setting up a group meeting two weeks after DiBella’s statement, Guillot asked Carlock in an email: “How do we keep all the parties focused to make some progress? I don’t believe that airing our dirty laundry in the press helps us close a deal.”

In another email the same day to Jonathan Fine, an attorney and sports industry advisor for the city, Guillot said he believed that, “after many months, I’ve finally earned some trust by Lou, Larry and Parney,” referring to DiBella, Squirrels co-owner Larry Botel, and Parnell.

However, Guillot added: “I do believe their public display is not fair to the City and to us given how much time we have invested with them to get to this point.”

In the following weeks, the parties held a group call with MLB-owned Minor League Baseball and met with stadium designer DLR during a ChamberRVA-led trip to Kansas City, Missouri, where Guillot, Carlock, Parnell and others toured the stadium for MLB’s Kansas City Royals.

But Guillot’s hopes of having earned DiBella’s trust were soon dashed – as Guillot relayed in an email to Fine, Richmond CAO Saunders and Leonard Sledge, the city’s then-economic development director.

Describing a call he had with DiBella the previous day – the same day that City Council approved the initial development deal with RVA Diamond Partners – Guillot wrote that DiBella had said “that he should have objected more to our team getting selected by the City and that I’m no friend of his.”

“I told him while I don’t expect to win his friendship, we do need to work together productively and that negative quotes in the media by him undermines our ability to convince bond investors that we have an exceptional project and that we’re all rowing in the same direction,” Guillot wrote, adding: “perception matters.”

“He of course took great offense at this and claims he’s not said anything untrue. As we wrapped up the call, he said he should just sell the team because the hassle isn’t worth it,” Guillot wrote. “I asked him what his price is because I might be able to pull together an investor group to take him out. Of course, he said he wants to wait for the new ballpark to be built…”

‘We still have a lot of trust to rebuild’

Site work started this fall on CarMax Park, which will replace the adjacent, nearly 40-year-old Diamond. (Skyshots Photography)

As tensions were growing between the developers and the Squirrels, they’d also grown between the city and Republic, the lead developer on RVA Diamond Partners that had brought locally based Thalhimer and Chicago-based Loop into the fold.

In early April 2023, a week before DiBella made his frustrations public, Republic sent the city a list of issues with the project that it wanted addressed before it would sign off on a formal development deal. One of those issues was whether the ballpark budget, which by that point had grown to over $90 million, was not sufficient to the city.

A gulf had formed between the parties over the desired capacity and cost of the ballpark, which RVA Diamond Partners had been planning as a 9,000-seat stadium. The Squirrels were insisting on a 10,000-capacity venue – a change that, among others, would ultimately push the ballpark’s cost to over $117 million.

In an email to Republic later that month, Saunders, the CAO, said the city had proposed a financing plan for the stadium, “sized in a manner that we believe is appropriate for the City, that further reduces the financial risk for RVADP while increasing the financial risk for the City.”

Later, while insisting on a meeting with the developers the next day, Saunders added in that email: “We still have a lot of trust to rebuild to get back to a position of feeling comfortable with moving forward with this partnership. Hearing your response tomorrow will be critical to knowing whether we should continue working to reach agreement.”

A deal with RVA Diamond Partners would ultimately be reached. But, soon after the development agreement was approved by City Council, Republic notified Thalhimer that it was exiting the project and “confirmed in writing that it would not continue to participate in the development,” Thalhimer has said.

Republic also notified the city that it had made an offer to Thalhimer and Loop “that would remove us from RVA Diamond Partners and enable them to move forward with the development of the Diamond District,” Republic’s Jordan Kramer said in a May 2023 email to Richmond’s Saunders and Sledge.

“If accepted, Republic would no longer be party to the teaming or operating agreements,” said Kramer, son of Republic board chairman Richard Kramer. “We are waiting to see if Loop and Thalhimer agree to our terms but until we get a firm answer, there’s nothing else we can do at this time.”

Republic had previously told the city that it would deliver by the day of Kramer’s email an operating agreement and governance documents for RVA Diamond Partners, which the three companies were restructuring. The LLC had been structured, according to Republic’s lawsuit, with Republic and Loop each owning 40% and Thalhimer owning 20%.

In a prior email to a lawyer for RVA Diamond Partners, John O’Neill – an attorney with Hunton Andrews Kurth, the city’s outside legal counsel – said the group had “reported that meaningful progress was being made in (the) LLC’s restructuring” and “conversations with additional equity participants were advancing…,” but that Thalhimer had since informed the city that “restructuring progress has stalled.”

With no documents delivered by the date they’d said they would be, Saunders, the city CAO, sent the three companies an email terminating their negotiations on the Diamond District.

“This notification of the consequences of (RVA Diamond Partners’) failure to make such delivery followed the prior failure of RVADP to (1) deliver such governance documents with the terms the City required and (2) execute and deliver the Development Agreement and Purchase and Sale Agreement in a timely manner…” Saunders’ email said.

“We are very disappointed that this action is occurring. But after months of negotiations with RVADP after its selection as the preferred proposer for the Diamond District project…the City can wait no longer for RVADP to resolve whatever internal issues it is facing and risk losing its ability to timely undertake this critical economic development priority.”

The timing of the ballpark had become more urgent in light of MLB’s deadline for all pro baseball venues to meet new facility standards by Opening Day 2025. Months before Saunders’ email, MLB had required $3 million in upgrades to The Diamond that the city had to spend to keep the Squirrels playing there in the meantime.

By the time final terms for the original development deal had been reached, however, officials acknowledged that the ballpark would not meet the 2025 deadline and started aiming instead for spring 2026 – an extension that MLB has appeared to allow.

Look for Part 2 of this story in tomorrow’s BizSense.

Fiasco is spelled F I A S C O.

The average man in the street won’t follow this twisted story. Not because the writing is bad (it isn’t), not because he doesn’t have an interest in watching professional baseball in Richmond (he does), but because it’s one more example of folks with a whole lot of money trying to get a whole lot more money. I’ll put up with paying what will likely be $20 to park, $15 beers (ouch!), $10 hot dogs (is it too much to ask to have relish and onions available in the new ballpark?) and whatever happens next as I’m certain the story will… Read more »

Here here Phil! Jonathan’s writing, as always, is wonderful as is his investigative acumen. Too bad the subject matter is a tangled web. Just want to say “Play Ball!!” and enjoy.

I live in the city, and most of my neighbors are indifferent to a new baseball stadium. That’s not a representative sample, but to me it shows that the attitude of city residents that we don’t want to pay for a private company’s stadium, which killed the Shockoe plan in 2014, hasn’t completely changed in the decade since.

Thank you.

Baseball is a special interest esp in a city of Richmond’s side. A very expensive special interest.

The Shockoe plan was not paid for by the city. City covered the much needed flood and infrastructure improvements, the development paid for the rest. It should have been downtown, it would be done, at a much lower cost and be halfway through the debt service.

This truly is a religion for some people. The average man on the street does not need to watch minor league baseball.

Agreed, America’s Pastime .

I guess the 428,541 who watched games there in 2023 aren’t the so called “average man.” Good grief, the team led all of AA baseball in total and average attendance in 2023 and average over 7K fans per game last season. Almost every family with children I know of try to go to at least one squirrels game each season.

430,000 in a metro of about 1.4 million is only about 30%, well below “average” , therefore the “average man” doesn’t need to watch baseball. Simple math.

Your math assumes none of the 30 percent are the same people. There are thousands of repeat customers in that 430k number. I would like to see the statistic of how many customers are city residents.

Oh so now we count metro population even though the city has to do all the heavy lifting on this? Get out of here with that. City population is 229k, attendance is 428k. Charlotte Knights – a AAA team – had attendance 498k in a city w/ population of 911k.

Crapping on Richmond and the Squirrels is the true National Pastime of a lot of commenters in this site.

A regional amenity that the city pays the entire freight on… some might say “whats the big deal, cities all over the country do this”. Not so much. Usually regional amenities are paid for by larger jurisdictions that span the metro. King County for Seattle, Multanomah county for Portland, Mecklenburg County for Charlotte, Miami-Dade for Miami, Harris County for Houston, the list goes on… this BS that Richmond frequently is saddled with is a result of Virginia laws for independent cities… Which makes it all the more frustrating when VCU gobbles up land and takes it off the tax rolls…

Interesting read. I’m not sure I understand why the details on how the sausage is made have any impact on whether you’ll enjoy a baseball game there? You’ll endure and can accept what are high but going rate costs but this – THIS! – which IMO is basically rich guy/company saber rattling and paperwork fights is a bridge too far?