Nearly four years after going into Chapter 11 bankruptcy to protect its Manchester real estate holdings and a year since emerging with an apparent turnaround plan, a Southside church is once again threatened with losing its property.

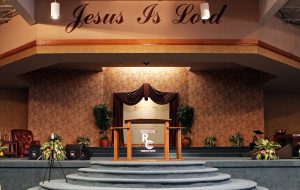

A lender is pushing to foreclose on 16 parcels owned by Richmond Christian Center, including its main church building at 214 Cowardin Ave., after the congregation missed revenue marks and fell out of compliance with its court-approved bankruptcy reorganization plan.

Meanwhile, the church’s bankruptcy trustee is trying to keep foreclosure at bay, arguing a more traditional sale process is best, while holding out hope that parishioners – and even the church’s founding pastor – could come up with the last-minute funds.

The properties, a mix of empty commercial and residential lots and small commercial buildings centered around the church’s 44,000-square-foot sanctuary, serve as collateral on a loan borrowed from Foundation Capital Resources.

The church first defaulted on that loan about four years ago, which forced it into bankruptcy after FCR sought to foreclose.

In this latest attempt, FCR filed a complaint June 30 in Richmond federal court, arguing for its right to foreclose on the collateral in light of RCC failing to live up to certain terms of its bankruptcy plan.

That plan, approved in early 2016, ordered RCC to adhere to a five-year business model that includes paying its bills on time, paying back creditors and bankruptcy administration fees, and increasing its tithes and other forms of revenue.

“Unfortunately we’re back to the beginning,” said Chris Perkins, an attorney with LeClairRyan representing RCC’s bankruptcy trustee Bruce Matson.

“We have determined that the church operationally doesn’t have the finances to comply with the confirmed Chapter 11 plan,” Perkins said, adding that tithing and additional revenue didn’t climb to expected levels. “We gave it a chance to work but it’s at the point where we can’t let it linger.”

In hopeful lieu of foreclosure, the trustee has asked the court for permission to modify the Chapter 11 plan to allow for the sale of the property through a traditional sales process, rather than foreclosure.

Perkins said momentum in the Manchester real estate market could help bring in more money than an all-out distressed sale.

The church’s 16 parcels sit on a total of about 5 acres. Their combined assessed value, according to the city, is around $4 million.

“FCR wants to foreclose. We would rather see a sale process where we can invite bidders and get more money than it would at foreclosure,” Perkins said.

Perkins said last week they’ve had recent interest from two parties.

A hearing is set for Aug. 16, where lawyers for both FCR and the church will argue their case.

A sale isn’t a foregone conclusion. The church’s leadership and members still have a chance to come up with a solution, Perkins said.

Ray Partridge, one of three church members leading the congregation since the bankruptcy, declined to comment when reached by phone earlier this month.

FCR is represented by attorney Paul Campsen of Kaufman & Canoles. He did not return calls seeking comment.

Nearly four years after going into Chapter 11 bankruptcy to protect its Manchester real estate holdings and a year since emerging with an apparent turnaround plan, a Southside church is once again threatened with losing its property.

A lender is pushing to foreclose on 16 parcels owned by Richmond Christian Center, including its main church building at 214 Cowardin Ave., after the congregation missed revenue marks and fell out of compliance with its court-approved bankruptcy reorganization plan.

Meanwhile, the church’s bankruptcy trustee is trying to keep foreclosure at bay, arguing a more traditional sale process is best, while holding out hope that parishioners – and even the church’s founding pastor – could come up with the last-minute funds.

The properties, a mix of empty commercial and residential lots and small commercial buildings centered around the church’s 44,000-square-foot sanctuary, serve as collateral on a loan borrowed from Foundation Capital Resources.

The church first defaulted on that loan about four years ago, which forced it into bankruptcy after FCR sought to foreclose.

In this latest attempt, FCR filed a complaint June 30 in Richmond federal court, arguing for its right to foreclose on the collateral in light of RCC failing to live up to certain terms of its bankruptcy plan.

That plan, approved in early 2016, ordered RCC to adhere to a five-year business model that includes paying its bills on time, paying back creditors and bankruptcy administration fees, and increasing its tithes and other forms of revenue.

“Unfortunately we’re back to the beginning,” said Chris Perkins, an attorney with LeClairRyan representing RCC’s bankruptcy trustee Bruce Matson.

“We have determined that the church operationally doesn’t have the finances to comply with the confirmed Chapter 11 plan,” Perkins said, adding that tithing and additional revenue didn’t climb to expected levels. “We gave it a chance to work but it’s at the point where we can’t let it linger.”

In hopeful lieu of foreclosure, the trustee has asked the court for permission to modify the Chapter 11 plan to allow for the sale of the property through a traditional sales process, rather than foreclosure.

Perkins said momentum in the Manchester real estate market could help bring in more money than an all-out distressed sale.

The church’s 16 parcels sit on a total of about 5 acres. Their combined assessed value, according to the city, is around $4 million.

“FCR wants to foreclose. We would rather see a sale process where we can invite bidders and get more money than it would at foreclosure,” Perkins said.

Perkins said last week they’ve had recent interest from two parties.

A hearing is set for Aug. 16, where lawyers for both FCR and the church will argue their case.

A sale isn’t a foregone conclusion. The church’s leadership and members still have a chance to come up with a solution, Perkins said.

Ray Partridge, one of three church members leading the congregation since the bankruptcy, declined to comment when reached by phone earlier this month.

FCR is represented by attorney Paul Campsen of Kaufman & Canoles. He did not return calls seeking comment.

That intersection of Cowardin and Semmes is Main and Main for the future of Manchester. A new plan for those four corners needs to be adopted.