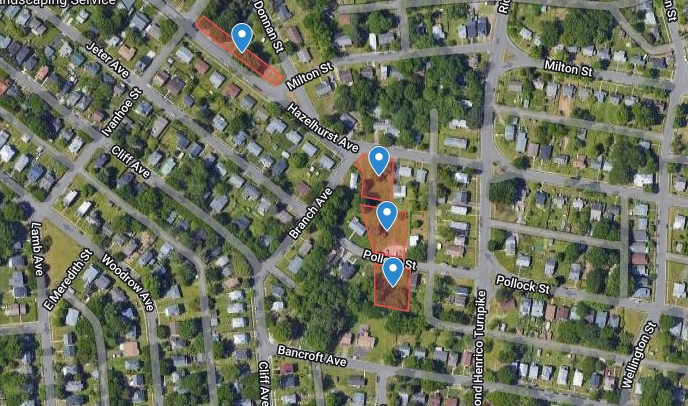

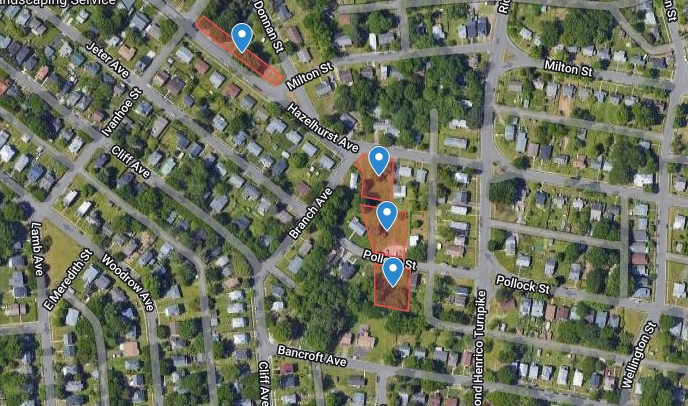

Four of the six parcels that were found to be unbuildable are in Northside’s Providence Park neighborhood. (Google map)

An effort by the city to unload surplus properties to help increase Richmond’s stock of lower-income housing has turned out to include lots that have been deemed unbuildable.

Last year, the city agreed to sell 15 parcels it had declared as surplus for $1 each to the Maggie Walker Community Land Trust, which manages the Richmond Land Bank, with the condition that the lots be developed as income-based housing or community gardens.

Eighteen months later, an analysis by the nonprofit has determined that eight of the parcels are not immediately buildable, due to such issues as utility easements running through the properties, topographical challenges making development too expensive, or ongoing disputes over ownership.

MWCLT is now seeking to return six of those parcels back to the city, after having spent a $20,000 grant on engineering and legal fees as part of its assessment. The two parcels that are in ownership disputes are to remain in a state of limbo until the disputes are resolved, and the remaining seven that the nonprofit deemed to be buildable are to be sold to developers through an upcoming solicitation.

The parcel at 3602 Delaware Ave. is one of two involved in ownership disputes. (City of Richmond property record photo)

The findings were shared in a meeting of the land bank’s Citizens Advisory Panel late last month. During the virtual meeting, panel member Lynn McAteer questioned why the city hadn’t made its own determination of the lots’ buildability before deeding them to the land trust through a combined quitclaim deed.

“Almost half of them aren’t really buildable, so there wasn’t really any investigation or due diligence done on them before they were transferred,” said McAteer, an administrator with the nonprofit Better Housing Coalition and one of two City Council appointees on the panel.

“The CLT spent money and resources on doing the engineering and on the legal work on all 15. Does it make sense to try to do some of that due diligence before the community land bank says we want these properties?” McAteer asked, noting the funds spent on assessing lots that are unbuildable.

Flora Valdes-Dapena, a coordinator for the land bank and MWCLT who presented the findings, replied that such work would be welcomed from the city, adding that the nonprofit does not have access to sewer alignments and other infrastructure information that the city treats as sensitive.

“In an ideal world, we would do that,” Valdes-Dapena said, noting financial challenges faced by the land bank, which she said does not have a dedicated funding stream from the city or MWCLT.

Referring to the city, McAteer added, “Maybe they could just provide some of that initial information so we don’t waste time looking at properties that aren’t viable,” to which Valdes-Dapena replied: “Speaking frankly, that’s something that we would like in the future.”

On the Zoom call was Sharon Ebert, the city’s deputy chief administrative officer for planning and economic development, who oversaw the sale agreement in 2021 and was appointed to chair the panel earlier this year.

Ebert did not speak during the discussion and did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Erica Sims, the land trust’s CEO, said the nonprofit spent a year working with the city to identify the 15 parcels as potential housing opportunities from among a larger list of surplus city properties. The parcels are the first to be deeded to the land trust through the surplus designation process, whereas most properties go to the land bank through foreclosures and tax-delinquent sales.

Dozens more city-owned properties are slated to go to the land trust through a similar process, as the city has earmarked 36 parcels in its real estate disposition plan for MWCLT specifically. Adopted last year, the biennial plan totals 77 properties, 24 of which are slated for sale to other housing nonprofits through an RFP process.

While she described the results of this initial transfer as “disappointing,” Sims said going through it will improve the process moving forward.

“I know that for everyone it’s been disappointing that the first batch was only 15 properties, and that out of those, several will have to be returned because they’re not viable. But it’s my opinion that the city and the CLT are really trying to be creative and see (if there is) any free land that the city has control over that can be developed as affordable housing,” Sims said Wednesday.

“It’s not your typical transfer of sale, and so it has come with a lot of learning about how we need to analyze these properties and what is possible within them. I think we will continue to try to identify more properties with the city, but they’re not going to get less funky,” she said.

Citing as an example one property that by appearances looked to be a prime development opportunity, only to find out later after digging through records that it perennially floods, Sims said a challenge is that many surplus properties have been owned by the city so long that associated records are not always easy to find.

“Those records, they’re somewhere in the city, but they’re not tied to the property records necessarily,” she said.

Sims said the $20,000 spent on the due diligence was from a grant from Virginia Housing, a state agency. She said the grant was intended to be used for such work, so she doesn’t consider it a loss of funds for the group.

“It took a fair amount of time just to receive it, but the grant is specifically for doing predevelopment feasibility work,” she said. “Virginia Housing recognizes that for nonprofits and developers in general, that’s money that’s really at risk, because you may spend that money and then learn at the end of that that you don’t have a developable or significantly developable property.”

The group used Ratchet Designs for the engineering work, and Mark A. Fleckenstein & Associates was its legal counsel.

The parcels deemed to be unbuildable include five in the Northside and one in the West End. Four involve sewer alignments crossing the property: 5913 Fergusson Road, a triangular quarter-acre lot near St. Christopher’s School; and in Providence Park, three adjoining parcels at 431 Hazelhurst Ave. and 410 and 429 Pollock St. have a sewer alignment running through them.

Another triangular lot, in Highland Park Southern Tip, is sloped at enough of an angle that infrastructure costs would make construction difficult and unfeasible, according to the analysis. The sixth parcel, at 3201 Hazelhurst Ave., is a linear-shaped lot in front of existing homes’ front yards and includes a public sidewalk.

The two parcels involving ownership disputes are 3602 Delaware Ave., also in Providence Park, and 4809 Old Warwick Road in South Richmond. In her presentation, Valdes-Dapena said the group would wait for those disputes to be resolved before taking any action on them.

The property at 4809 Old Warwick Road, also involved in an ownership dispute. (Property record photo)

As for the seven developable lots, Valdes-Dapena said they would be offered to developers through an RFP in January or early February and are expected to produce as many as 22 housing units.

Those parcels include 1903 and 1905 Semmes Ave. near Manchester, a pair of side-by-side parcels totaling over a half-acre; 6101, 6109 and 6117 Forest Hill Ave., contiguous parcels totaling 1 acre across from Willow Oaks Country Club; 3100 Alvis Ave., a 1.5-acre parcel that’s partially buildable due to a stream; and a quarter-acre parcel at 207 E. Ladies Mile Road.

Any for-sale homes built on those parcels would be required to participate in the land trust’s home ownership model, in which the homes are kept affordable through a ground-lease approach. MWCLT owns the land and leases it to an income-qualified homebuyer for little to no lease payments, and the buyer then only has to purchase the house and agrees to keep only half the proceeds when the house is later sold. The remaining equity stays with the house to keep it affordable for the next buyer.

Valdes-Dapena noted in her presentation that it’s not uncommon for the land trust to end up with unbuildable lots. In such cases, it typically makes those available for community gardens or greenspace if feasible.

While it’s opting to return the six unbuildable parcels to the city, Sims said Wednesday that the land trust looks forward to continuing to work with the city to identify potential properties and improve the process.

“We have a much better checklist now, between us and the city, about how we have to evaluate these properties to make sure that they are developable, and we can really cut down on the time it takes us to do that analysis,” she said. “We do hope to continue to work with the city to make this a more efficient process for both sides.”

Four of the six parcels that were found to be unbuildable are in Northside’s Providence Park neighborhood. (Google map)

An effort by the city to unload surplus properties to help increase Richmond’s stock of lower-income housing has turned out to include lots that have been deemed unbuildable.

Last year, the city agreed to sell 15 parcels it had declared as surplus for $1 each to the Maggie Walker Community Land Trust, which manages the Richmond Land Bank, with the condition that the lots be developed as income-based housing or community gardens.

Eighteen months later, an analysis by the nonprofit has determined that eight of the parcels are not immediately buildable, due to such issues as utility easements running through the properties, topographical challenges making development too expensive, or ongoing disputes over ownership.

MWCLT is now seeking to return six of those parcels back to the city, after having spent a $20,000 grant on engineering and legal fees as part of its assessment. The two parcels that are in ownership disputes are to remain in a state of limbo until the disputes are resolved, and the remaining seven that the nonprofit deemed to be buildable are to be sold to developers through an upcoming solicitation.

The parcel at 3602 Delaware Ave. is one of two involved in ownership disputes. (City of Richmond property record photo)

The findings were shared in a meeting of the land bank’s Citizens Advisory Panel late last month. During the virtual meeting, panel member Lynn McAteer questioned why the city hadn’t made its own determination of the lots’ buildability before deeding them to the land trust through a combined quitclaim deed.

“Almost half of them aren’t really buildable, so there wasn’t really any investigation or due diligence done on them before they were transferred,” said McAteer, an administrator with the nonprofit Better Housing Coalition and one of two City Council appointees on the panel.

“The CLT spent money and resources on doing the engineering and on the legal work on all 15. Does it make sense to try to do some of that due diligence before the community land bank says we want these properties?” McAteer asked, noting the funds spent on assessing lots that are unbuildable.

Flora Valdes-Dapena, a coordinator for the land bank and MWCLT who presented the findings, replied that such work would be welcomed from the city, adding that the nonprofit does not have access to sewer alignments and other infrastructure information that the city treats as sensitive.

“In an ideal world, we would do that,” Valdes-Dapena said, noting financial challenges faced by the land bank, which she said does not have a dedicated funding stream from the city or MWCLT.

Referring to the city, McAteer added, “Maybe they could just provide some of that initial information so we don’t waste time looking at properties that aren’t viable,” to which Valdes-Dapena replied: “Speaking frankly, that’s something that we would like in the future.”

On the Zoom call was Sharon Ebert, the city’s deputy chief administrative officer for planning and economic development, who oversaw the sale agreement in 2021 and was appointed to chair the panel earlier this year.

Ebert did not speak during the discussion and did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Erica Sims, the land trust’s CEO, said the nonprofit spent a year working with the city to identify the 15 parcels as potential housing opportunities from among a larger list of surplus city properties. The parcels are the first to be deeded to the land trust through the surplus designation process, whereas most properties go to the land bank through foreclosures and tax-delinquent sales.

Dozens more city-owned properties are slated to go to the land trust through a similar process, as the city has earmarked 36 parcels in its real estate disposition plan for MWCLT specifically. Adopted last year, the biennial plan totals 77 properties, 24 of which are slated for sale to other housing nonprofits through an RFP process.

While she described the results of this initial transfer as “disappointing,” Sims said going through it will improve the process moving forward.

“I know that for everyone it’s been disappointing that the first batch was only 15 properties, and that out of those, several will have to be returned because they’re not viable. But it’s my opinion that the city and the CLT are really trying to be creative and see (if there is) any free land that the city has control over that can be developed as affordable housing,” Sims said Wednesday.

“It’s not your typical transfer of sale, and so it has come with a lot of learning about how we need to analyze these properties and what is possible within them. I think we will continue to try to identify more properties with the city, but they’re not going to get less funky,” she said.

Citing as an example one property that by appearances looked to be a prime development opportunity, only to find out later after digging through records that it perennially floods, Sims said a challenge is that many surplus properties have been owned by the city so long that associated records are not always easy to find.

“Those records, they’re somewhere in the city, but they’re not tied to the property records necessarily,” she said.

Sims said the $20,000 spent on the due diligence was from a grant from Virginia Housing, a state agency. She said the grant was intended to be used for such work, so she doesn’t consider it a loss of funds for the group.

“It took a fair amount of time just to receive it, but the grant is specifically for doing predevelopment feasibility work,” she said. “Virginia Housing recognizes that for nonprofits and developers in general, that’s money that’s really at risk, because you may spend that money and then learn at the end of that that you don’t have a developable or significantly developable property.”

The group used Ratchet Designs for the engineering work, and Mark A. Fleckenstein & Associates was its legal counsel.

The parcels deemed to be unbuildable include five in the Northside and one in the West End. Four involve sewer alignments crossing the property: 5913 Fergusson Road, a triangular quarter-acre lot near St. Christopher’s School; and in Providence Park, three adjoining parcels at 431 Hazelhurst Ave. and 410 and 429 Pollock St. have a sewer alignment running through them.

Another triangular lot, in Highland Park Southern Tip, is sloped at enough of an angle that infrastructure costs would make construction difficult and unfeasible, according to the analysis. The sixth parcel, at 3201 Hazelhurst Ave., is a linear-shaped lot in front of existing homes’ front yards and includes a public sidewalk.

The two parcels involving ownership disputes are 3602 Delaware Ave., also in Providence Park, and 4809 Old Warwick Road in South Richmond. In her presentation, Valdes-Dapena said the group would wait for those disputes to be resolved before taking any action on them.

The property at 4809 Old Warwick Road, also involved in an ownership dispute. (Property record photo)

As for the seven developable lots, Valdes-Dapena said they would be offered to developers through an RFP in January or early February and are expected to produce as many as 22 housing units.

Those parcels include 1903 and 1905 Semmes Ave. near Manchester, a pair of side-by-side parcels totaling over a half-acre; 6101, 6109 and 6117 Forest Hill Ave., contiguous parcels totaling 1 acre across from Willow Oaks Country Club; 3100 Alvis Ave., a 1.5-acre parcel that’s partially buildable due to a stream; and a quarter-acre parcel at 207 E. Ladies Mile Road.

Any for-sale homes built on those parcels would be required to participate in the land trust’s home ownership model, in which the homes are kept affordable through a ground-lease approach. MWCLT owns the land and leases it to an income-qualified homebuyer for little to no lease payments, and the buyer then only has to purchase the house and agrees to keep only half the proceeds when the house is later sold. The remaining equity stays with the house to keep it affordable for the next buyer.

Valdes-Dapena noted in her presentation that it’s not uncommon for the land trust to end up with unbuildable lots. In such cases, it typically makes those available for community gardens or greenspace if feasible.

While it’s opting to return the six unbuildable parcels to the city, Sims said Wednesday that the land trust looks forward to continuing to work with the city to identify potential properties and improve the process.

“We have a much better checklist now, between us and the city, about how we have to evaluate these properties to make sure that they are developable, and we can really cut down on the time it takes us to do that analysis,” she said. “We do hope to continue to work with the city to make this a more efficient process for both sides.”

If you don’t want it, don’t take it. Simple. The city didn’t donate due-diligence fees, they donated land. Same as if it was in a flood plain.

If the folks in the article truly wanted to be creative, instead of just complaining, they could have speant all of 5 minutes and decided to make the unbuildable lots community space like raised gardens and provided something that benefits all the taxpayers in that area.

Could the unbuildable lots be offered to adjacent land owners for a nominal fee?

That’s an idea I had pondered as well.

I am also curious how the land trust is just able to decide to take the lazy way out and give the land back instead of building said community gardens on those parcels deemed not buildable.

Another example of how the local community loses out. The donations were meant for local improvements not simply an easy way to build a home at profit.

Fred,

That’s a fair point, but a non-profit shouldn’t have to spend $20,000 to determine whether the lots are buildable, especially when some of the driving factors are proprietary information that the city has. If that continues to be the case, they likely will take you up on your offer and say “No thank you,” even to lots that could work because of the cost and uncertainty. And who benefits from that?

Wouldn’t you rather the non-profit spend that money on preparing the lot or developing it, rather than on legal fees?

MWCLT’s specific and stated goal was to use them to build housing or community gardens. It’s not the cities job to do the due diligence of a company, non profit or not.

“Last year, the city agreed to sell 15 parcels it had declared as surplus for $1 each to the Maggie Walker Community Land Trust,… with the condition that the lots be developed as income-based housing or community gardens.”

Note the emphasis on community gardens… No need for a buildable lot if you’re going to grow a garden. Quit complaining for getting basically free land.

The city needs money. It’s it’s reasoning behind the tax increases.

It should be selling these lots to raise money, until the point it no longer needs money. We will know when that happens when they start dropping taxes

Um… the city has a $17m – 21m budget surplus. and a $70m general fund surplus. They have proposed 5 cent tax rebate. I believe the incentive is to sell random properties, which just require maintenance and don’t contribute to tax revenue..

The City could create more housing by up zoning the land along Grove Avenue to allow 5 to 12 story tall apartment buildings and replace some of the houses with muti story buildings. Technically one 5 story apartment building at the intersection of Libbie Ave and Grove would create ten times more housing then this.

Carl: It’s easy to imagine two four or five story apartment or condo buildings at the south east corner of Grove and Libbie.

I agree. The taller the better in my opinion as there are limited options for sprawling. The city/developers would need to build up in order to accommodate more housing. The taller buildings, while accommodating more units to begin with, could even be a mix of uses, having both income-based/affordable units and market-rate units – maybe even with commercial on the bottom.