After weeding out lots that it deemed unbuildable, the Maggie Walker Community Land Trust is getting ready to sell off its first batch of surplus city properties for development of lower-income housing.

The nonprofit, which manages the Richmond Land Bank, is accepting purchase applications through April 3 for six parcels that the city had declared as surplus so that they could contribute to Richmond’s low-income housing stock.

The Monday deadline is for prequalified applicants, meaning developers – both nonprofit and private for-profit – that have shown they have means to purchase and develop the property. An earlier deadline for applicants that had yet to be qualified passed last week, just over a month after a call for applications went out in February.

The six parcels are what remain of a 15-parcel group that the city agreed to sell to MWCLT for $1 each, with the condition that the lots be developed as income-based housing or community gardens. The land trust later determined that eight of the parcels were not immediately buildable because of issues such as utility easements, topographical challenges or ownership disputes.

Since then, one of the seven other parcels that had been considered buildable was removed from the list because of a correction in ownership records.

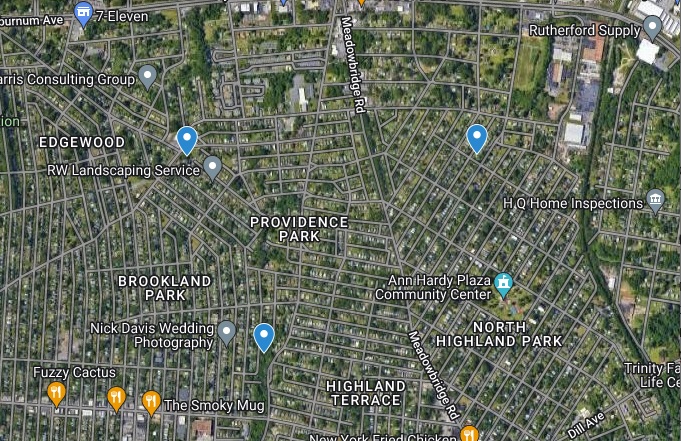

The six parcels being offered for sale include: 3100 Alvis Ave. in Brookland Park, a 1.5-acre parcel that’s partially buildable due to a stream; 207 E. Ladies Mile Road, a quarter-acre parcel in Providence Park; and 1903 and 1905 Semmes Ave., a pair of side-by-side parcels near Manchester totaling more than a half-acre.

The parcel at 3602 Delaware Ave. is involved in an ownership dispute. (City of Richmond property record photo)

Also on the list is 3602 Delaware Ave, a 0.13-acre parcel that had been considered unbuildable because of an ownership dispute. That dispute is being resolved with assistance from MWCLT’s legal counsel, said Flora Valdes-Dapena, a coordinator for the land bank and MWCLT.

Rounding out the parcels for sale is 5913 Fergusson Road, a triangular quarter-acre lot near St. Christopher’s School. The lot was previously deemed unbuildable because of a sewer alignment crossing the property, but Valdes-Dapena said it was determined that the lot can be developed around the alignment.

Removed from the list were three parcels at 6101, 6109 and 6117 Forest Hill Ave., which total 1 acre and sit across from Willow Oaks Country Club.

Riverside Brick & Supply Co., a 150-year-old firm, owned the land until 1971, when the city took it by eminent domain to build the Powhite Parkway. A portion of the parcels was deeded to the Richmond Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 1976, and the rest was deeded back to Riverside Brick in 2018, Valdes-Dapena said.

“There was a dispute as to which part was city-owned and which part was privately owned,” she said. “Ultimately we found that the city-owned portion was only a small sliver along the right of way of Forest Hill Avenue, so we came to an agreement with the city to return it.”

Other properties returned to the city include three adjoining parcels in Providence Park – 431 Hazelhurst Ave. and 410 and 429 Pollock St. – that were deemed unbuildable because of a sewer alignment running through them. Also returned to the city was 3201 Hazelhurst Ave., a linear-shaped lot in front of existing homes’ front yards that includes a public sidewalk.

Also transferred was 4809 Old Warwick Road, an improved lot with a house on it that, it turned out, was being used by a nonprofit as its office. Valdes-Dapena said the city agreed to transfer the property to the nonprofit.

The property at 4809 Old Warwick Road was deeded to a nonprofit that had been using it as an office. (Property record photo)

While the parcels with easements or topographical challenges could potentially be used as community gardens, Valdes-Dapena said they were being returned to the city because MWCLT “simply doesn’t have the organizational capacity to manage an urban agriculture program right now.”

Noting MWCLT’s involvement in Bensley Agrihood, a farm-focused community in North Chesterfield, she added, “We may in the future as we gain more experience with the Bensley Agrihood project, but for now the (Richmond Land Bank) program will continue focusing on affordable housing.”

Officials have said the discoveries made about the properties show the surplus approach is a learning process. MWCLT CEO Erica Sims has said a challenge is that many surplus properties have been owned by the city so long that associated records are not always easy to find.

With these six parcels positioned for sale, Sims said this week, “We feel like, with these remaining properties that we have, we’re going to be able to move pretty smoothly to develop them as housing, so that feels good.”

Where the previous group of seven parcels was expected to yield as many as 22 housing units, Valdes-Dapena said the six remaining buildable lots would likely produce fewer – about 16 or so. Units can include rentals or owner-occupied homes.

Valdes-Dapena said sale prices would be based on a variety of factors and would likely be discounted below assessed value for nonprofit buyers. Sales to for-profit developers would be based on assessed value, she said.

She said last month’s solicitation has garnered two applications so far, with two more expected by Monday’s deadline. Any properties that do not receive purchase offers or aren’t ultimately transferred would go to MWCLT, she said.

The timeline for transfers would vary based on the resolutions of title and legal issues. In the case of the Delaware Avenue parcel that involves an ownership dispute, Valdes-Dapena said a buyer would be asked to reimburse the land trust for expenses related to resolving that dispute.

Any for-sale homes built on the parcels would be required to participate in the land trust’s home ownership model, in which the homes are kept affordable through a ground-lease approach.

Dozens more city-owned properties are slated to go to the land trust through a similar process. The city has earmarked 36 parcels in its real estate disposition plan for MWCLT specifically. Adopted in 2021, the biennial plan totals 77 properties, 24 of which are slated for sale to other housing nonprofits through an RFP process.

After weeding out lots that it deemed unbuildable, the Maggie Walker Community Land Trust is getting ready to sell off its first batch of surplus city properties for development of lower-income housing.

The nonprofit, which manages the Richmond Land Bank, is accepting purchase applications through April 3 for six parcels that the city had declared as surplus so that they could contribute to Richmond’s low-income housing stock.

The Monday deadline is for prequalified applicants, meaning developers – both nonprofit and private for-profit – that have shown they have means to purchase and develop the property. An earlier deadline for applicants that had yet to be qualified passed last week, just over a month after a call for applications went out in February.

The six parcels are what remain of a 15-parcel group that the city agreed to sell to MWCLT for $1 each, with the condition that the lots be developed as income-based housing or community gardens. The land trust later determined that eight of the parcels were not immediately buildable because of issues such as utility easements, topographical challenges or ownership disputes.

Since then, one of the seven other parcels that had been considered buildable was removed from the list because of a correction in ownership records.

The six parcels being offered for sale include: 3100 Alvis Ave. in Brookland Park, a 1.5-acre parcel that’s partially buildable due to a stream; 207 E. Ladies Mile Road, a quarter-acre parcel in Providence Park; and 1903 and 1905 Semmes Ave., a pair of side-by-side parcels near Manchester totaling more than a half-acre.

The parcel at 3602 Delaware Ave. is involved in an ownership dispute. (City of Richmond property record photo)

Also on the list is 3602 Delaware Ave, a 0.13-acre parcel that had been considered unbuildable because of an ownership dispute. That dispute is being resolved with assistance from MWCLT’s legal counsel, said Flora Valdes-Dapena, a coordinator for the land bank and MWCLT.

Rounding out the parcels for sale is 5913 Fergusson Road, a triangular quarter-acre lot near St. Christopher’s School. The lot was previously deemed unbuildable because of a sewer alignment crossing the property, but Valdes-Dapena said it was determined that the lot can be developed around the alignment.

Removed from the list were three parcels at 6101, 6109 and 6117 Forest Hill Ave., which total 1 acre and sit across from Willow Oaks Country Club.

Riverside Brick & Supply Co., a 150-year-old firm, owned the land until 1971, when the city took it by eminent domain to build the Powhite Parkway. A portion of the parcels was deeded to the Richmond Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 1976, and the rest was deeded back to Riverside Brick in 2018, Valdes-Dapena said.

“There was a dispute as to which part was city-owned and which part was privately owned,” she said. “Ultimately we found that the city-owned portion was only a small sliver along the right of way of Forest Hill Avenue, so we came to an agreement with the city to return it.”

Other properties returned to the city include three adjoining parcels in Providence Park – 431 Hazelhurst Ave. and 410 and 429 Pollock St. – that were deemed unbuildable because of a sewer alignment running through them. Also returned to the city was 3201 Hazelhurst Ave., a linear-shaped lot in front of existing homes’ front yards that includes a public sidewalk.

Also transferred was 4809 Old Warwick Road, an improved lot with a house on it that, it turned out, was being used by a nonprofit as its office. Valdes-Dapena said the city agreed to transfer the property to the nonprofit.

The property at 4809 Old Warwick Road was deeded to a nonprofit that had been using it as an office. (Property record photo)

While the parcels with easements or topographical challenges could potentially be used as community gardens, Valdes-Dapena said they were being returned to the city because MWCLT “simply doesn’t have the organizational capacity to manage an urban agriculture program right now.”

Noting MWCLT’s involvement in Bensley Agrihood, a farm-focused community in North Chesterfield, she added, “We may in the future as we gain more experience with the Bensley Agrihood project, but for now the (Richmond Land Bank) program will continue focusing on affordable housing.”

Officials have said the discoveries made about the properties show the surplus approach is a learning process. MWCLT CEO Erica Sims has said a challenge is that many surplus properties have been owned by the city so long that associated records are not always easy to find.

With these six parcels positioned for sale, Sims said this week, “We feel like, with these remaining properties that we have, we’re going to be able to move pretty smoothly to develop them as housing, so that feels good.”

Where the previous group of seven parcels was expected to yield as many as 22 housing units, Valdes-Dapena said the six remaining buildable lots would likely produce fewer – about 16 or so. Units can include rentals or owner-occupied homes.

Valdes-Dapena said sale prices would be based on a variety of factors and would likely be discounted below assessed value for nonprofit buyers. Sales to for-profit developers would be based on assessed value, she said.

She said last month’s solicitation has garnered two applications so far, with two more expected by Monday’s deadline. Any properties that do not receive purchase offers or aren’t ultimately transferred would go to MWCLT, she said.

The timeline for transfers would vary based on the resolutions of title and legal issues. In the case of the Delaware Avenue parcel that involves an ownership dispute, Valdes-Dapena said a buyer would be asked to reimburse the land trust for expenses related to resolving that dispute.

Any for-sale homes built on the parcels would be required to participate in the land trust’s home ownership model, in which the homes are kept affordable through a ground-lease approach.

Dozens more city-owned properties are slated to go to the land trust through a similar process. The city has earmarked 36 parcels in its real estate disposition plan for MWCLT specifically. Adopted in 2021, the biennial plan totals 77 properties, 24 of which are slated for sale to other housing nonprofits through an RFP process.

Valdes-Dapena said they were being returned to the city because MWCLT “simply doesn’t have the organizational capacity to manage an urban agriculture program right now.” Which is Greek for “we just don’t feel like doing it and you all are suckers!”. How long are the taxpayers going to put up with this? It’s part of the deal they agreed to, they get free property and in return they use some of the land for community use. No one ever said they need to run an AG program. What are they claiming, they need to plant row crops, a grain silo… Read more »

Im not sure I follow? MWCLT’s web site states the build community housing, not other community uses. the land isn’t buildable for housing. Also, could you explain what tax dollars are being spent? They’re just not taking the free land. Just asking, not attacking your line of thought. thanks.

The original deal was they get the land for $1 (a price far below market value) for 2 things….build affordable housing and build community gardens/use space.

By Choosing to simply fail to do item #2 They are not complying with the agreement they made with the City. Doesn’t matter what their website says.

And whose been paying the city permit folks to do all the back end paperwork on the land they no longer want?

Their website clearly shows they don’t do farming or parks, perhaps they planned on offering the farming/park development to others? Perhaps a “Friends of” type non profit organization or neighborhood association. Doing some quick news reading, it appears they stated they “may” use them… they opted not to and are returning the land back to the city. The minimal time/cost by those city employees will be quickly be covered by the additional tax revenue for the developed parcels. I don’t think this is a big deal or cost. They appear to be mostly funded by corporations. At least the city… Read more »