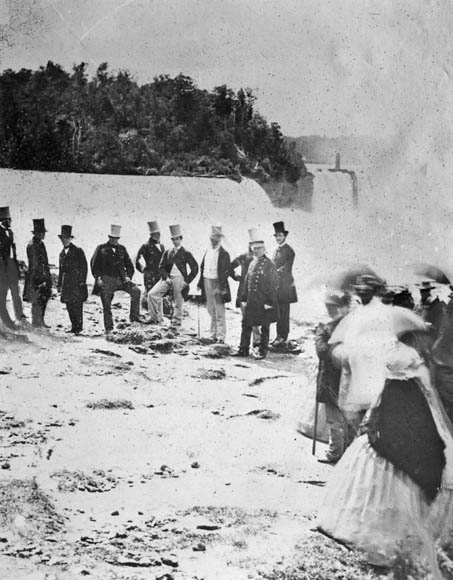

Mount Vernon has in its collection a painting depicting Edward and President James Buchanan as they visit George Washington’s tomb in October 1860. Painting by Thomas P. Rossiter. (Smithsonian American Art Museum, courtesy of The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association)

It’s nearing the end of spring semester. Many graduates are plotting grand tours, with Berlin, Bangkok or Barcelona surely on a GPS or two. Other grads may be heading to London for the coronation of Charles III, formerly the Prince of Wales, and Queen Consort Camilla on May 6.

For the pull-out-the-stops Westminster Abbey coronation The Wall Street Journal reports that the famously uncomfortable Gold State Coach, built in 1762, will be gussied up, and for modernity a bespoke crown emoji, inspired by Charles’ headdress, has been designed.

What most Richmond palace-watchers probably don’t know is this: While the new king has never seen Richmond, his great-great grandfather, King Edward VII (who reigned from 1901 to 1910), visited here in October 1860. He was an 18-year-old Prince of Wales then and since his trip to Canada and the United States was unofficial he traveled under the name Baron Renfrew, a title of the heir to the British throne. Of course, locals weren’t fooled. Wouldn’t the current Prince and Princess of Wales, William and his wife Kate Middleton, be spotted in Richmond if they showed up at a Scott’s Addition night spot, say at Don’t Look Back or Lucky AF?

Edward’s impromptu excursion to Richmond was controversial. Northern press coverage of the trip below the Mason-Dixon Line to a southern slave trading city was vitriolic, especially in The New York Times. It was just six months before the first shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, and whether true or not, the newspaper described the Richmond residents Edward encountered as louts – “rough,” “howling,” “villainous.” So much for Southern hospitality.

The 18-year-old heir to the throne, affectionately known as Bertie, embarked on the lengthy voyage with a 12-man entourage including his tutor, Major General Robert Bruce. They’d been dispatched by Bertie’s mum, Queen Victoria, on an experience-building goodwill trip (she would never make the crossing). After the posse landed in Canada, first stop was Montreal, where the prince dedicated the Victoria Bridge that crossed the St. Lawrence River. Next up was Ottawa, where he lay a cornerstone for the parliament building.

The party entered the United States at Detroit. All along, the popular prince’s presence delighted star-struck Americans at parades, receptions and balls. However, one Midwesterner who declined an invitation to the royal train was Abraham Lincoln, the Republican presidential candidate in 1860. The optics of a cabin-born “rail-splitter” schmoozing with a royal didn’t fit the campaign playbook. But the eldest son of Queen Victoria and German-born Prince Albert was embraced like a rock star by both everyday folks and the intelligentsia. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” author Harriet Beecher Stowe swooned that Edward was “the embodiment, in boy’s form, of a glorious related nation.”

In Washington, D.C., the prince stayed for three nights at the White House as the guest of bachelor President James Buchanan. The prince later said that a highlight of his U.S. sojourn was a Potomac River cruise hosted by Buchanan aboard the “Harriet Lane” (a steamer named for the president’s niece). They sailed to Mount Vernon, George Washington’s home, which would soon become one of the nation’s prime secular pilgrimage destinations. The estate had recently been acquired by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, an action that triggered the nation’s historic preservation movement that continues today. The two hours at Mount Vernon were filled with examining the unrestored and unfurnished mansion, and the tombs of the first president and his wife, Martha.

After leaving the nation’s capital, instead of heading north to planned stops in Baltimore and Philadelphia, Edward and crew veered south by rail unexpectedly to Richmond. Southern destinations hadn’t been scheduled because of intensifying North-South hostilities. But pressure came from prominent Virginians for Bertie to visit their state capital. Would the South sway the prince to its viewpoints or seek financial support?

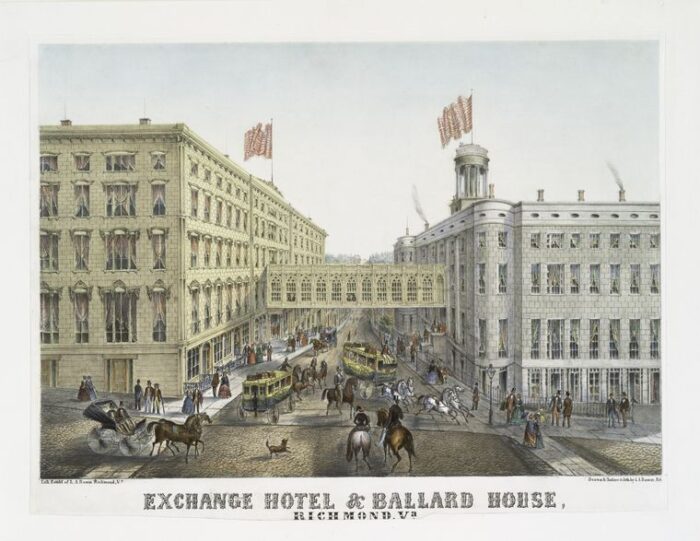

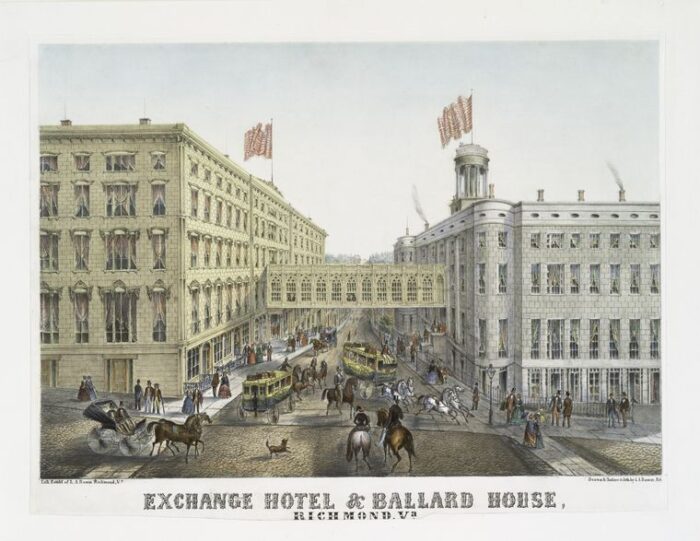

The Prince of Wales visited The Exchange Hotel, which stood at at the southeast corner of 14th and Franklin streets and was connected to the Ballard House.

On Saturday, Oct. 6, the Baron Renfrew gang arrived in Richmond aboard a red, white and blue flag-bedecked Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac train. From the station at East Broad and North Seventh streets, the men were driven by carriages to welcoming festivities at the state fairgrounds (Monroe Park now occupies the site). Then, a throng of a reported 5,000 people followed the prince’s carriage to Shockoe Slip where he was spending one night at the Ballard Hotel; he entered by a side door to avoid the onlookers. Safely in his suite, according to The New York Times, it wasn’t long before marauders filled the halls and pushed doors open with catcalls and the cries of: “Where is he?” At 7 p.m., Edward emerged for a sumptuous banquet with city bigwigs at the nearby Exchange Hotel. It lasted until 11. The Times reported archly that a ball initially had been planned in Edward’s honor, but that Richmonders couldn’t raise the funds.

On Sunday morning the prince and his men were driven up the hill for 11 a.m. services at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church (a still-vital parish today, located at East Grace and North Ninth streets). The sanctuary was packed while 5,000 gawkers stood outside. After the service, Edward remained glued to his pew as if in a kind of trance. Perhaps homesick at this stage of his journey, the voice of the church’s German-born rector the Rev. Charles Minnigerode had reminded him of that of his own strict father.

Edward and company were next driven across Ninth Street to Capitol Square and were ushered into the Capitol rotunda to view the life-size marble statue of George Washington. It had been sculpted by Jean-Antoine Houdon, a leading French sculptor of his generation. According to the Times, the tour was soon joined by a “rough, dirty crowd” that made “most unceremoniously personal remarks regarding the visitors’ attire.” With the Washington statue in mind, one resident shouted: “You like him, don’t you?” Another bullied, “Guess he whipped you British.” The prince maintained his royal demeanor (Richmond leaders would later assail The New York Times for what it considered fake news).

After the Capitol stop, Virginia’s new governor, John Letcher, had the visitors for refreshments at his residence in the Executive Mansion (and maybe some political talk). Then, after lunch at the Ballard Hotel, they were all off to visit two Richmond attractions. They went to St. John’s Episcopal Church on Church Hill. This was ironic since it was here, in 1775, that patriot Patrick Henry had called for “liberty or death” in the fight for independence from Great Britain. Then it was across town to Hollywood Cemetery to view the resting place of James Monroe. The fifth president had recently been re-interred in the then-fledgling cemetery from his initial resting place near lower Manhattan.

At 5 p.m. and probably exhausted, Edward and party boarded their train, waved to the Richmond crowd from the rear platform, and headed north to scheduled visits in Baltimore and Philadelphia.

On Nov. 15, 1860, the British group set sail from Portland, Maine, for home into a stormy Atlantic Ocean. It was hurricane season. Because of the weather the ship was a week late returning. While Queen Victoria had been nervous about the safety of Bertie (who turned 19 during the rough passage), perhaps her mood was ameliorated by souvenirs her eldest son brought her from the New World – two gray squirrels and a mud turtle.

As for Edward, he was 60 when he was crowned King of England. Come May 6, his great-great grandson, Charles III, will have waited 73 years, being the oldest heir ever to ascend the English throne.

Editor’s note: Guest commentator Edwin Slipek, a native Richmonder, is a writer, architectural historian and the co-editor of ArchitectureRichmond, an online encyclopedia of local design. Slipek’s great-great grandfather, Randall Holden, while studying at the College of Medicine of Maryland in 1860, wrote to his family living in Petersburg that he was hoping to catch a glimpse of Edward during the prince’s Baltimore visit.

Mount Vernon has in its collection a painting depicting Edward and President James Buchanan as they visit George Washington’s tomb in October 1860. Painting by Thomas P. Rossiter. (Smithsonian American Art Museum, courtesy of The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association)

It’s nearing the end of spring semester. Many graduates are plotting grand tours, with Berlin, Bangkok or Barcelona surely on a GPS or two. Other grads may be heading to London for the coronation of Charles III, formerly the Prince of Wales, and Queen Consort Camilla on May 6.

For the pull-out-the-stops Westminster Abbey coronation The Wall Street Journal reports that the famously uncomfortable Gold State Coach, built in 1762, will be gussied up, and for modernity a bespoke crown emoji, inspired by Charles’ headdress, has been designed.

What most Richmond palace-watchers probably don’t know is this: While the new king has never seen Richmond, his great-great grandfather, King Edward VII (who reigned from 1901 to 1910), visited here in October 1860. He was an 18-year-old Prince of Wales then and since his trip to Canada and the United States was unofficial he traveled under the name Baron Renfrew, a title of the heir to the British throne. Of course, locals weren’t fooled. Wouldn’t the current Prince and Princess of Wales, William and his wife Kate Middleton, be spotted in Richmond if they showed up at a Scott’s Addition night spot, say at Don’t Look Back or Lucky AF?

Edward’s impromptu excursion to Richmond was controversial. Northern press coverage of the trip below the Mason-Dixon Line to a southern slave trading city was vitriolic, especially in The New York Times. It was just six months before the first shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, and whether true or not, the newspaper described the Richmond residents Edward encountered as louts – “rough,” “howling,” “villainous.” So much for Southern hospitality.

The 18-year-old heir to the throne, affectionately known as Bertie, embarked on the lengthy voyage with a 12-man entourage including his tutor, Major General Robert Bruce. They’d been dispatched by Bertie’s mum, Queen Victoria, on an experience-building goodwill trip (she would never make the crossing). After the posse landed in Canada, first stop was Montreal, where the prince dedicated the Victoria Bridge that crossed the St. Lawrence River. Next up was Ottawa, where he lay a cornerstone for the parliament building.

The party entered the United States at Detroit. All along, the popular prince’s presence delighted star-struck Americans at parades, receptions and balls. However, one Midwesterner who declined an invitation to the royal train was Abraham Lincoln, the Republican presidential candidate in 1860. The optics of a cabin-born “rail-splitter” schmoozing with a royal didn’t fit the campaign playbook. But the eldest son of Queen Victoria and German-born Prince Albert was embraced like a rock star by both everyday folks and the intelligentsia. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” author Harriet Beecher Stowe swooned that Edward was “the embodiment, in boy’s form, of a glorious related nation.”

In Washington, D.C., the prince stayed for three nights at the White House as the guest of bachelor President James Buchanan. The prince later said that a highlight of his U.S. sojourn was a Potomac River cruise hosted by Buchanan aboard the “Harriet Lane” (a steamer named for the president’s niece). They sailed to Mount Vernon, George Washington’s home, which would soon become one of the nation’s prime secular pilgrimage destinations. The estate had recently been acquired by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, an action that triggered the nation’s historic preservation movement that continues today. The two hours at Mount Vernon were filled with examining the unrestored and unfurnished mansion, and the tombs of the first president and his wife, Martha.

After leaving the nation’s capital, instead of heading north to planned stops in Baltimore and Philadelphia, Edward and crew veered south by rail unexpectedly to Richmond. Southern destinations hadn’t been scheduled because of intensifying North-South hostilities. But pressure came from prominent Virginians for Bertie to visit their state capital. Would the South sway the prince to its viewpoints or seek financial support?

The Prince of Wales visited The Exchange Hotel, which stood at at the southeast corner of 14th and Franklin streets and was connected to the Ballard House.

On Saturday, Oct. 6, the Baron Renfrew gang arrived in Richmond aboard a red, white and blue flag-bedecked Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac train. From the station at East Broad and North Seventh streets, the men were driven by carriages to welcoming festivities at the state fairgrounds (Monroe Park now occupies the site). Then, a throng of a reported 5,000 people followed the prince’s carriage to Shockoe Slip where he was spending one night at the Ballard Hotel; he entered by a side door to avoid the onlookers. Safely in his suite, according to The New York Times, it wasn’t long before marauders filled the halls and pushed doors open with catcalls and the cries of: “Where is he?” At 7 p.m., Edward emerged for a sumptuous banquet with city bigwigs at the nearby Exchange Hotel. It lasted until 11. The Times reported archly that a ball initially had been planned in Edward’s honor, but that Richmonders couldn’t raise the funds.

On Sunday morning the prince and his men were driven up the hill for 11 a.m. services at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church (a still-vital parish today, located at East Grace and North Ninth streets). The sanctuary was packed while 5,000 gawkers stood outside. After the service, Edward remained glued to his pew as if in a kind of trance. Perhaps homesick at this stage of his journey, the voice of the church’s German-born rector the Rev. Charles Minnigerode had reminded him of that of his own strict father.

Edward and company were next driven across Ninth Street to Capitol Square and were ushered into the Capitol rotunda to view the life-size marble statue of George Washington. It had been sculpted by Jean-Antoine Houdon, a leading French sculptor of his generation. According to the Times, the tour was soon joined by a “rough, dirty crowd” that made “most unceremoniously personal remarks regarding the visitors’ attire.” With the Washington statue in mind, one resident shouted: “You like him, don’t you?” Another bullied, “Guess he whipped you British.” The prince maintained his royal demeanor (Richmond leaders would later assail The New York Times for what it considered fake news).

After the Capitol stop, Virginia’s new governor, John Letcher, had the visitors for refreshments at his residence in the Executive Mansion (and maybe some political talk). Then, after lunch at the Ballard Hotel, they were all off to visit two Richmond attractions. They went to St. John’s Episcopal Church on Church Hill. This was ironic since it was here, in 1775, that patriot Patrick Henry had called for “liberty or death” in the fight for independence from Great Britain. Then it was across town to Hollywood Cemetery to view the resting place of James Monroe. The fifth president had recently been re-interred in the then-fledgling cemetery from his initial resting place near lower Manhattan.

At 5 p.m. and probably exhausted, Edward and party boarded their train, waved to the Richmond crowd from the rear platform, and headed north to scheduled visits in Baltimore and Philadelphia.

On Nov. 15, 1860, the British group set sail from Portland, Maine, for home into a stormy Atlantic Ocean. It was hurricane season. Because of the weather the ship was a week late returning. While Queen Victoria had been nervous about the safety of Bertie (who turned 19 during the rough passage), perhaps her mood was ameliorated by souvenirs her eldest son brought her from the New World – two gray squirrels and a mud turtle.

As for Edward, he was 60 when he was crowned King of England. Come May 6, his great-great grandson, Charles III, will have waited 73 years, being the oldest heir ever to ascend the English throne.

Editor’s note: Guest commentator Edwin Slipek, a native Richmonder, is a writer, architectural historian and the co-editor of ArchitectureRichmond, an online encyclopedia of local design. Slipek’s great-great grandfather, Randall Holden, while studying at the College of Medicine of Maryland in 1860, wrote to his family living in Petersburg that he was hoping to catch a glimpse of Edward during the prince’s Baltimore visit.

Thanks Eddie, great piece !

All in all, a rather nice welcome for a Royal who’s family torched the Whitehouse a mere 40 years earlier.

I nominate Eddie to head up the Virginia Royal Visit Committee for Charles’ US tour in 2024!

There is a painting from that visit that details a who’s who of DC by Thomas Rossiter, painted in 1860; Link to Image on WIkimedia.

Richmond was a lot nicer then than it is today .

Not for a significant portion of the population who were contributing free labor.

Do you realize there is more to history than just slavery?