A red banner attached to the cast-iron fence of The Valentine history center recently caught my eye. “A finished museum is a dead one,” it read. Indeed, a fitting mantra for an institution that is aggressively current as it marks its 125th year.

But something occurred to me after visiting two stunning and revelatory exhibitions at two other institutions this spring, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A museum needn’t be limited to collecting things solely from the past. It can affect the creation of future work directly by supporting budding talent. That is something the VMFA has done since 1940, having awarded $6 million in fellowships to 1,200 artists working in the state.

It’s a coincidence that the VMFA’s current exhibition, “Benjamin Wigfall and Communications Village,” and a recent Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, showing of works by Cy Twombly, remind us that these Virginia-born artists received career-launching boosts when the VMFA awarded them significant financial assistance. A May 25, 1952, Richmond Times-Dispatch article featured a headshot of each artist, side by side.

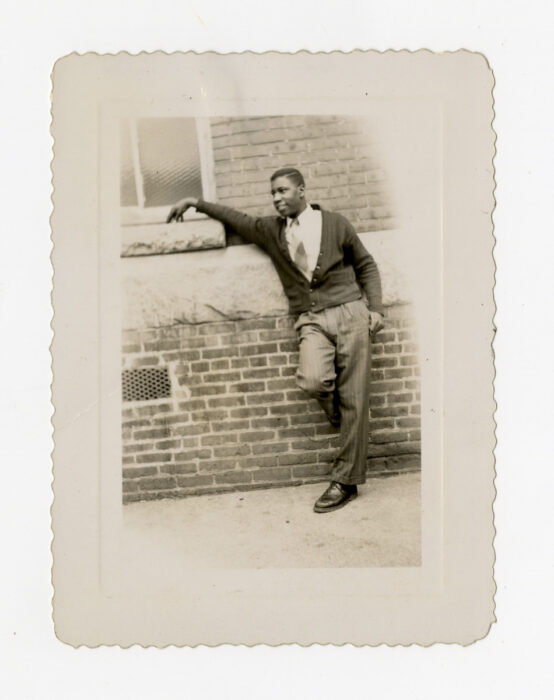

These two young talents represented different sides of the social, economic and racial divide. Benjamin Wigfall (1930-2017) grew up in North Church Hill; his father was a railroad fireman, his mother a tobacco factory worker turned beautician. During his years at Armstrong High School, the promising youngster was introduced to the VMFA by a teacher. After high school, he applied for and received VMFA assistance in pursuing a fine arts degree at Hampton Institute (now university).

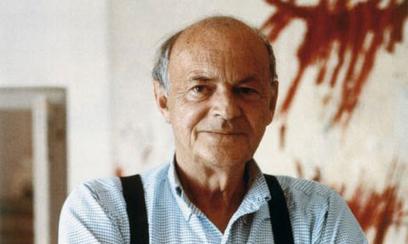

Cy Twombly Jr. (1928-2011) was a native of the college town of Lexington, where his father was the athletic director and a a popular coach at Washington & Lee University. Twombly used his 1952 VMFA fellowship for an extended European exploratory tour with artist Robert Rauschenberg. The sojourn led to Twombly marrying an aristocratic and well-to-do Italian woman. Entranced by the ancient world, he stayed and worked in Rome for the remainder of his life (with regular trips back to Lexington).

Upon graduation from Hampton, Wigfall pursued graduate studies in fine arts at Yale. He then became an accomplished printmaker and taught printmaking at the State University of New York, New Paltz. As the 1960s morphed into the ’70s, his personal and political focus shifted from civil rights to Black culture and empowerment (a childhood and lifetime friend was L. Douglas Wilder, a Richmond lawyer who was elected the nation’s first African American governor). Wigfall eventually made his way to Kingston, New York, a city 90 miles up the Hudson from New York City, where he established a printmaking studio. It soon became a community arts center called Communications Village, where the gifted artist instructed and inspired numerous people, young and old, in making art.

Perhaps few people within or outside the art world knew of Wigfall until this spring when the VMFA opened its extremely powerful and inspirational exhibition, “Benjamin Wigfall and Communications Village.” Sarah Eckhardt, a VMFA curator, was a sharply focused force in creating this exhibit with the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz. As the author of seminal parts of the show’s excellent catalog, Eckhardt weaves a clear narrative of Wigfall’s trajectory from talented child on Church Hill to master educator in New York State. In addition to Wigfall’s bold artwork, the exhibition includes pieces created by his New York colleagues and peers to create a “you-are-there” experience. Wigfall’s New York studio was closed in 1983 and he returned to academia. This must-see event runs until Sept. 10.

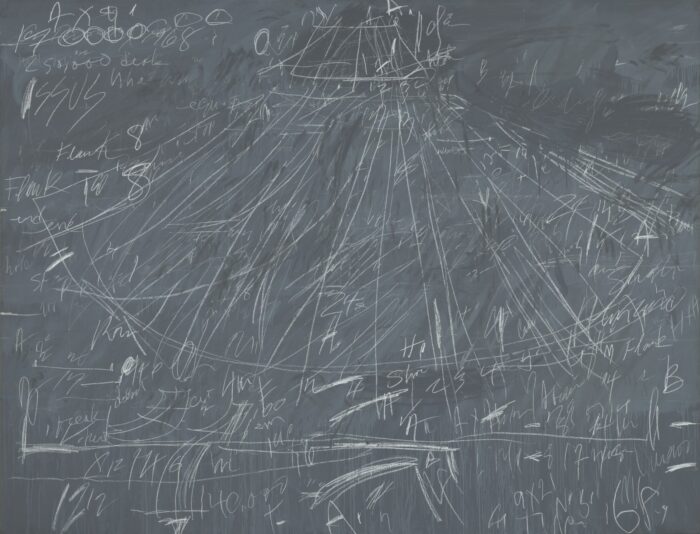

Unlike Wigfall, Twombly, an abstract expressionist painter and sculptor, experienced international rock-stardom in the contemporary art world. He lived to see one of his canvases, “Untitled,” fetch $70.5 million. A featured piece in “Making Past Present: Cy Twombly,” a long-anticipated retrospective shown at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles before Boston, was a major work lent by the VMFA. “Synopsis of a Battle,” painted in 1968, was borrowed from its usual spot in the Sydney and Frances Lewis collection of the VMFA on North Arthur Ashe Boulevard. It served as an exhibition highlight in Malibu and in Back Bay Boston (where I saw the exhibition). The piece, painted with lowly commercial grade paint and crayon, appears to be inscrutable markings scribbled on a blackboard. Closer inspection, however, shows a detailed scheme for a military maneuver. It describes the Battle of Issus (in 333 B.C.E.) between King Darius and Alexander the Great. The work was displayed in Boston in a pride-of-place location within the 60-object exhibition.

In its examination of Wigfall’s lesser-known works and times, the VMFA has pulled out all the stops to show Wigfall’s abstract paintings and prints to a handsome advantage. You learn things. But the show also re-creates the excitement and promise of the artist’s time at Communications Village in Kingston. This elegant installation is a crisp-looking and well-paced visual encyclopedia of Wigfall’s career.

One of the first pieces shown is a black ink drawing (rather unremarkable and conservative). “The House on 30th Street” was drawn by Wigfall ca. 1947-49. It unmistakably depicts a Church Hill dwelling and the artist deftly handles the perspective. But close examination shows a window with wavy glass opening onto a porch. Or is it a dartboard? It is a coil, or spiral, actually, and amid the somber frame house and leafless trees, you can sense Wigfall’s energy needing a release. The form suggests that dynamic shapes were yet to come from this artist. His energy is hard to suppress.

The VMFA caught the Wigfall bug early. It purchased his abstract oil painting “Chimneys” in 1951, when Wigfall was 21. The painting was inspired by industrial smokestacks that he passed regularly as he traveled through Shockoe Bottom. “There is a nobility in something very common, and that could be anywhere,” he later explained as his inspiration for the striking painting. Wigfall became the youngest artist ever to have work collected by the VMFA (which bought a second work soon thereafter). And the museum recently acquired many additional artworks and archival pieces from his estate.

I hope many future budding artists will visit this exhibition and, well, learn that possible fellowships await. Who knows where that may lead?

“Benjamin Wigfall and Communications Village” continues at the VMFA through Sept. 10. There is a special admission charge for this exhibit, which includes admission to a concurrent temporary exhibition, “Whitfield Lovell: Passages.”

A red banner attached to the cast-iron fence of The Valentine history center recently caught my eye. “A finished museum is a dead one,” it read. Indeed, a fitting mantra for an institution that is aggressively current as it marks its 125th year.

But something occurred to me after visiting two stunning and revelatory exhibitions at two other institutions this spring, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A museum needn’t be limited to collecting things solely from the past. It can affect the creation of future work directly by supporting budding talent. That is something the VMFA has done since 1940, having awarded $6 million in fellowships to 1,200 artists working in the state.

It’s a coincidence that the VMFA’s current exhibition, “Benjamin Wigfall and Communications Village,” and a recent Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, showing of works by Cy Twombly, remind us that these Virginia-born artists received career-launching boosts when the VMFA awarded them significant financial assistance. A May 25, 1952, Richmond Times-Dispatch article featured a headshot of each artist, side by side.

These two young talents represented different sides of the social, economic and racial divide. Benjamin Wigfall (1930-2017) grew up in North Church Hill; his father was a railroad fireman, his mother a tobacco factory worker turned beautician. During his years at Armstrong High School, the promising youngster was introduced to the VMFA by a teacher. After high school, he applied for and received VMFA assistance in pursuing a fine arts degree at Hampton Institute (now university).

Cy Twombly Jr. (1928-2011) was a native of the college town of Lexington, where his father was the athletic director and a a popular coach at Washington & Lee University. Twombly used his 1952 VMFA fellowship for an extended European exploratory tour with artist Robert Rauschenberg. The sojourn led to Twombly marrying an aristocratic and well-to-do Italian woman. Entranced by the ancient world, he stayed and worked in Rome for the remainder of his life (with regular trips back to Lexington).

Upon graduation from Hampton, Wigfall pursued graduate studies in fine arts at Yale. He then became an accomplished printmaker and taught printmaking at the State University of New York, New Paltz. As the 1960s morphed into the ’70s, his personal and political focus shifted from civil rights to Black culture and empowerment (a childhood and lifetime friend was L. Douglas Wilder, a Richmond lawyer who was elected the nation’s first African American governor). Wigfall eventually made his way to Kingston, New York, a city 90 miles up the Hudson from New York City, where he established a printmaking studio. It soon became a community arts center called Communications Village, where the gifted artist instructed and inspired numerous people, young and old, in making art.

Perhaps few people within or outside the art world knew of Wigfall until this spring when the VMFA opened its extremely powerful and inspirational exhibition, “Benjamin Wigfall and Communications Village.” Sarah Eckhardt, a VMFA curator, was a sharply focused force in creating this exhibit with the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz. As the author of seminal parts of the show’s excellent catalog, Eckhardt weaves a clear narrative of Wigfall’s trajectory from talented child on Church Hill to master educator in New York State. In addition to Wigfall’s bold artwork, the exhibition includes pieces created by his New York colleagues and peers to create a “you-are-there” experience. Wigfall’s New York studio was closed in 1983 and he returned to academia. This must-see event runs until Sept. 10.

Unlike Wigfall, Twombly, an abstract expressionist painter and sculptor, experienced international rock-stardom in the contemporary art world. He lived to see one of his canvases, “Untitled,” fetch $70.5 million. A featured piece in “Making Past Present: Cy Twombly,” a long-anticipated retrospective shown at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles before Boston, was a major work lent by the VMFA. “Synopsis of a Battle,” painted in 1968, was borrowed from its usual spot in the Sydney and Frances Lewis collection of the VMFA on North Arthur Ashe Boulevard. It served as an exhibition highlight in Malibu and in Back Bay Boston (where I saw the exhibition). The piece, painted with lowly commercial grade paint and crayon, appears to be inscrutable markings scribbled on a blackboard. Closer inspection, however, shows a detailed scheme for a military maneuver. It describes the Battle of Issus (in 333 B.C.E.) between King Darius and Alexander the Great. The work was displayed in Boston in a pride-of-place location within the 60-object exhibition.

In its examination of Wigfall’s lesser-known works and times, the VMFA has pulled out all the stops to show Wigfall’s abstract paintings and prints to a handsome advantage. You learn things. But the show also re-creates the excitement and promise of the artist’s time at Communications Village in Kingston. This elegant installation is a crisp-looking and well-paced visual encyclopedia of Wigfall’s career.

One of the first pieces shown is a black ink drawing (rather unremarkable and conservative). “The House on 30th Street” was drawn by Wigfall ca. 1947-49. It unmistakably depicts a Church Hill dwelling and the artist deftly handles the perspective. But close examination shows a window with wavy glass opening onto a porch. Or is it a dartboard? It is a coil, or spiral, actually, and amid the somber frame house and leafless trees, you can sense Wigfall’s energy needing a release. The form suggests that dynamic shapes were yet to come from this artist. His energy is hard to suppress.

The VMFA caught the Wigfall bug early. It purchased his abstract oil painting “Chimneys” in 1951, when Wigfall was 21. The painting was inspired by industrial smokestacks that he passed regularly as he traveled through Shockoe Bottom. “There is a nobility in something very common, and that could be anywhere,” he later explained as his inspiration for the striking painting. Wigfall became the youngest artist ever to have work collected by the VMFA (which bought a second work soon thereafter). And the museum recently acquired many additional artworks and archival pieces from his estate.

I hope many future budding artists will visit this exhibition and, well, learn that possible fellowships await. Who knows where that may lead?

“Benjamin Wigfall and Communications Village” continues at the VMFA through Sept. 10. There is a special admission charge for this exhibit, which includes admission to a concurrent temporary exhibition, “Whitfield Lovell: Passages.”

Interesting! Thanks for writing about Wigfall — everyone knows enough about Twombly of course, but I have even familiar with New Paltz and the area (home to one of my favorite Hotels, Mohonk Mountain House, which puts the Retreat in Bath County to shame) — many people in NYS don’t even know there are mountain towns with little colleges that resemble Western towns in NYS) but never heard of Wigfall even though you say he was pretty important to one of SUNY’s better visual art programs. I was inspired to check out his stuff, since I like some abstract art… Read more »

It seems to be a theme generally — for a long time Virginia’s best and brightest had to leave VA to get their due. It seems actually that these two actually got their due somewhat IN VA to an extent before they left – VMFA was buying Wigfall’s paintings starting in 1951, as you point out. The period in Virginia between the Jefferson era and the civil was is not much studied, but glimpses of it are seen in when you read about the Young Edgar Allen Poe, and it seems there was a huge cultural decline in Virginia BEFORE… Read more »

Now, we call places like this “Mississippi” — we call them “Lebanon” and “North Korea. Increasingly, we are calling them “New York State” — my whole life, it seemed that not only the best college grads left NYS, but even most of the best High School grads too — seems a 1/4 of my HS class lives in North Carolina, and it wasn’t the bottom quarter either. When I moved to Richmond, I already knew a guy from my home region, who I went to college and bars with, who was already a professor at VCU. There were already countless… Read more »

Re: others’ comments about in and out migration-A prophet isn’t honored in her own country-an ancient concept, arising before the borders of VA or NYS were contemplated. As usual Edwin Slipek gives us insights and context, and expresses all of it better than anyone else could.

In Virginia’s hey day, their best got PLENTY of attention.

Same thing in NYS.

Prophets are a different story.

Thanks again, Ed Slipek, for another insightful review. I’d like to give credit to VMFA’s former senior archivist, Courtney Tkacz, who was responsible for acquiring and processing the trove of archival resources from the Wigfall estate in time for them to be used to support new scholarship on Wigfall for the exhibition and catalogue. Please note all of the archival documentation that Dr. Eckhardt included in the Wigfall show, and look for Twombly’s letters from the archives in the Twombly exhibition!