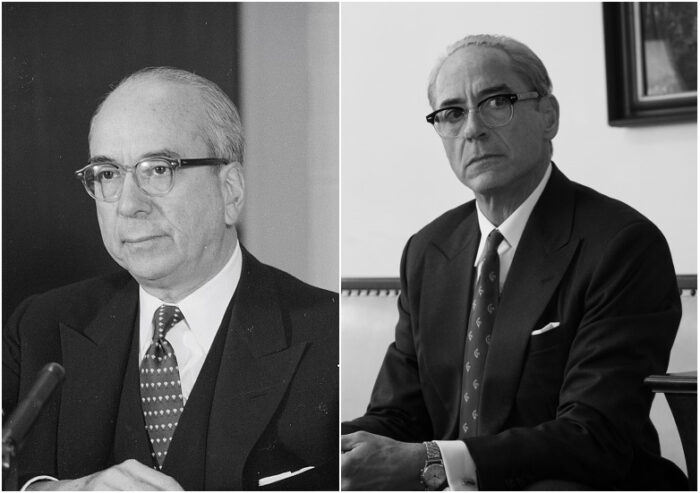

Robert Downey Jr. as Strauss (left) and Cillian Murphy as Oppenheimer in a scene from the film. (Courtesy Universal Pictures)

The film reviews for “Oppenheimer” are glowing: “… It crackles, hurdles and whooshes,” reports The Wall Street Journal, “… one of the few standout works of cinema released this decade.”

Cillian Murphy plays J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist whose team built the atomic bomb that changed the course of history. Matt Damon depicts saw-edged U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves, who oversaw the operation. And “Oscar” is written all over Robert Downey Jr.’s performance as Rear Admiral Lewis L. Strauss Jr., the chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission who later briefly served after World War II as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s secretary of commerce.

Strauss was also Oppenheimer’s adversary.

What most Virginians don’t know is that Strauss (1896-1974) was reared in Richmond’s Fan District and went on to become a financially and politically influential Horatio Alger. But while locals don’t recognize his name, as statues of historical figures from other eras are being removed, “Oppenheimer” paints Strauss as an essential player of the Cold War years – and not in a positive light.

Early in the film (based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin) we see Strauss hot-stepping gratuitously down a sidewalk from the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University. As a trustee of the think tank, he welcomes the brilliant Oppenheimer to the campus in hopes that he’ll accept the directorship of the prestigious center. These two men of the Old Testament schmooze as they get acquainted. Oppenheimer (a nonpracticing Jew from New York City), questions Strauss (devoutly Jewish since boyhood) on the pronunciation of his name. Strauss explains that “Straws” is a Southern thing. And soon thereafter Strauss clarifies that he is not a physicist, but a former traveling shoe salesman.

In a following scene, the pair spot Albert Einstein, a founder of the advanced study center (played by Tom Conti). As the retired genius strolls the university grounds Oppenheimer enthusiastically approaches and the two men chat privately. Observing the physicists from out of ear range, Strauss assumes they are discussing, and possibly undermining, him. Thus, the stage is set for later clashes between these strong-willed atomic age titans. Things won’t end so well for Strauss despite his brilliant financial successes, long national public service, generous philanthropy and piety.

Who was Lewis Lichtenstein Strauss Jr.? Born in West Virginia to native Richmond parents, he grew up in Richmond at 1142 West Ave. For elementary school he attended Stonewall Jackson, nearby at 1520 W. Main St. (the grand old building more recently housed Baja Bean Co. restaurant, and now Jardin wine bistro). Strauss’ mother was an artist who had studied with John A. Elder, a Fredericksburg-born painter and sculptor who painted iconic paintings with Confederate themes. The family faithfully attended Congregation Beth Ahabah, a Reform synagogue on West Franklin Street.

Strauss attended John Marshall High School, then the city’s only white public high school. It was located downtown in the 800 block of East Marshall Street. In 1913 Strauss would have graduated first in his class had he not contracted typhoid fever. He then eschewed a University of Virginia scholarship to join his family’s wholesale shoe business, Fleishman and Morris. He worked there for three years and never entered college. He did, however, devour a highly regarded physics textbook.

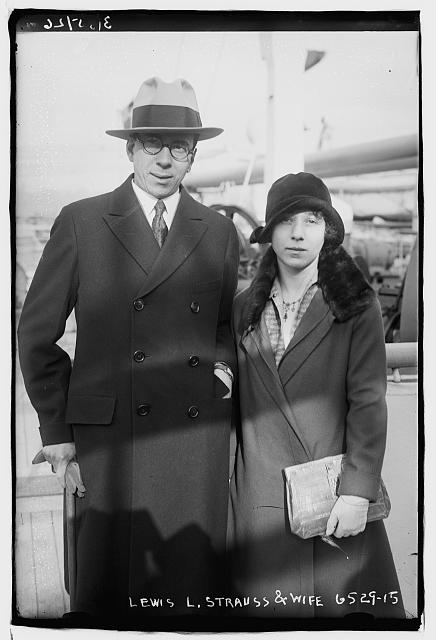

At the encouragement of his civic-minded mother, in 1917 at age 21, Strauss took a train to Washington, D.C., to volunteer for the Belgian War Relief board. The effort was led by Herbert Hoover (not yet president). World War I in Europe was underway, and the United States was not yet involved. Hoover was so impressed with Strauss’ smarts and manners that he hired him as his personal secretary. Traveling to Europe together, Strauss became a wartime food relief administrator. Afterward, he moved to New York where he joined Kuhn, Loeb & Co., Wall Street’s second-largest investment bank after J.P. Morgan. He didn’t hurt himself by marrying Alice Hanauer, the daughter of a firm partner. She was a Vassar graduate and artist who made pottery. Strauss became a firm partner at age 32 and would become immensely wealthy from investments, especially in the steel industry.

In 1938, after Kristallnacht in Germany, Strauss used his considerable contacts to implore congressional Republicans to allow 20,000 Jewish refugees to enter the United States. They declined, citing already high unemployment because of the continuing Great Depression.

When the United States entered World War II, Strauss first joined the U.S. Navy Reserve, then active duty. He held a desk job because of bad eyesight (his vision was impaired when he was 10 years old from a rock fight, probably with one of Richmond’s many neighborhood boy gangs). In 1945 Strauss was promoted from lieutenant commander to rear admiral. On July 16, 1945, the nuclear Trinity bomb was tested under the direction of Oppenheimer and Lt. Gen. Groves in New Mexico. President Harry F. Truman ordered bombs dropped on Japan soon thereafter.

In 1953 Strauss was appointed by President Eisenhower, whose campaigns he had supported generously, as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. He served until 1958. It was during this period that animus arose between Strauss and Oppenheimer over peacetime uses of atomic energy, specifically regarding the exportation of radioactive isotopes; Strauss was opposed. He became an advocate of peaceful uses of atomic energy by free enterprise. A die-hard, patriotic Republican, Strauss also believed that Oppenheimer had long-held leftist/socialist leanings. Seeing a potential threat to national security, after Strauss encouraged J. Edgar Hoover to investigate Oppenheimer, the physicist was denied federal security clearance. Their frayed relationship led to misery on both sides, as the second half of the film dramatizes.

In 1958 Eisenhower installed Strauss as secretary of commerce during a congressional recess. In 1959, having been nominated for a full appointment, Strauss underwent a long and humiliating hearing, and eventual defeat, for the post. Democratic senators had used their muscle before senatorial and presidential elections to thwart both Eisenhower and Strauss. Both Sens. John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson (two later presidents), voted against Strauss in a close contest.

So, at 70, Strauss retired to his 2,000-acre farm at Brandy Station near Culpeper, Virginia. It had 800 head of angus cattle and a mansion constructed of Virginia stone. There, he wrote two books (his memoir was a New York Times bestseller). He also continued his educational, medical, cultural and Jewish philanthropies (during his New York years he was president of the venerable Temple Emanu-El, a Reform congregation on Fifth Avenue). He also served as a trustee of the Metropolitan Opera.

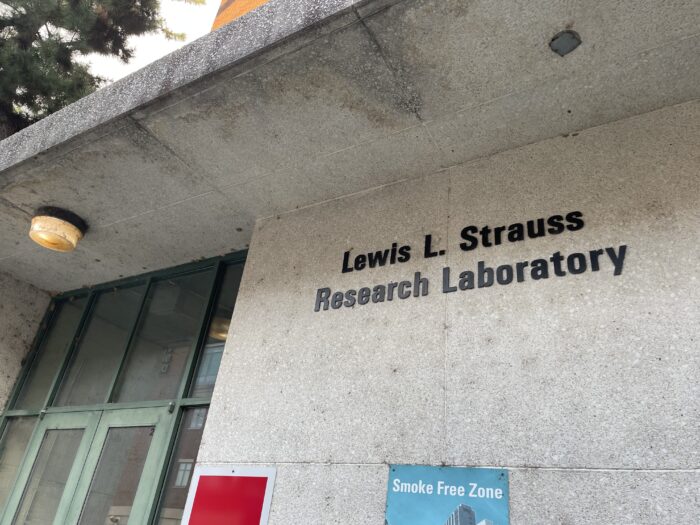

Back in Virginia, he had terms as a trustee of Hampton Institute (now University), the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Virginia Historical Society (now the Virginia Museum of History & Culture). He donated funds to the Medical College of Virginia (now the VCU School of Medicine) for research in cancer and other related diseases. The Lewis Strauss Research Laboratory on the MCV campus at 527 N. 12th St. bears his name (it was in this facility that Dr. David Hume, whose team performed the world’s first successful kidney transplant at Harvard, continued his work, as did transplant pioneers Hyung Mo Lee and Richard Lower).

Both his parents had succumbed to cancer and in 1974, Strauss himself died of the disease. His funeral was at Temple Emanu-El in Manhattan and he is buried in Richmond’s Hebrew Cemetery at Fourth and Hospital streets.

In “Oppenheimer,” Robert Downey Jr. resurrects Strauss. According to The New Yorker, the actor provides “the most densely textured performance of his career…he all but commandeers the film.”

See it.

Correction: An earlier version of this column incorrectly state the address of Lewis Strauss’s childhood home in Richmond. It was 1142 West Ave.

Robert Downey Jr. as Strauss (left) and Cillian Murphy as Oppenheimer in a scene from the film. (Courtesy Universal Pictures)

The film reviews for “Oppenheimer” are glowing: “… It crackles, hurdles and whooshes,” reports The Wall Street Journal, “… one of the few standout works of cinema released this decade.”

Cillian Murphy plays J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist whose team built the atomic bomb that changed the course of history. Matt Damon depicts saw-edged U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves, who oversaw the operation. And “Oscar” is written all over Robert Downey Jr.’s performance as Rear Admiral Lewis L. Strauss Jr., the chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission who later briefly served after World War II as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s secretary of commerce.

Strauss was also Oppenheimer’s adversary.

What most Virginians don’t know is that Strauss (1896-1974) was reared in Richmond’s Fan District and went on to become a financially and politically influential Horatio Alger. But while locals don’t recognize his name, as statues of historical figures from other eras are being removed, “Oppenheimer” paints Strauss as an essential player of the Cold War years – and not in a positive light.

Early in the film (based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin) we see Strauss hot-stepping gratuitously down a sidewalk from the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University. As a trustee of the think tank, he welcomes the brilliant Oppenheimer to the campus in hopes that he’ll accept the directorship of the prestigious center. These two men of the Old Testament schmooze as they get acquainted. Oppenheimer (a nonpracticing Jew from New York City), questions Strauss (devoutly Jewish since boyhood) on the pronunciation of his name. Strauss explains that “Straws” is a Southern thing. And soon thereafter Strauss clarifies that he is not a physicist, but a former traveling shoe salesman.

In a following scene, the pair spot Albert Einstein, a founder of the advanced study center (played by Tom Conti). As the retired genius strolls the university grounds Oppenheimer enthusiastically approaches and the two men chat privately. Observing the physicists from out of ear range, Strauss assumes they are discussing, and possibly undermining, him. Thus, the stage is set for later clashes between these strong-willed atomic age titans. Things won’t end so well for Strauss despite his brilliant financial successes, long national public service, generous philanthropy and piety.

Who was Lewis Lichtenstein Strauss Jr.? Born in West Virginia to native Richmond parents, he grew up in Richmond at 1142 West Ave. For elementary school he attended Stonewall Jackson, nearby at 1520 W. Main St. (the grand old building more recently housed Baja Bean Co. restaurant, and now Jardin wine bistro). Strauss’ mother was an artist who had studied with John A. Elder, a Fredericksburg-born painter and sculptor who painted iconic paintings with Confederate themes. The family faithfully attended Congregation Beth Ahabah, a Reform synagogue on West Franklin Street.

Strauss attended John Marshall High School, then the city’s only white public high school. It was located downtown in the 800 block of East Marshall Street. In 1913 Strauss would have graduated first in his class had he not contracted typhoid fever. He then eschewed a University of Virginia scholarship to join his family’s wholesale shoe business, Fleishman and Morris. He worked there for three years and never entered college. He did, however, devour a highly regarded physics textbook.

At the encouragement of his civic-minded mother, in 1917 at age 21, Strauss took a train to Washington, D.C., to volunteer for the Belgian War Relief board. The effort was led by Herbert Hoover (not yet president). World War I in Europe was underway, and the United States was not yet involved. Hoover was so impressed with Strauss’ smarts and manners that he hired him as his personal secretary. Traveling to Europe together, Strauss became a wartime food relief administrator. Afterward, he moved to New York where he joined Kuhn, Loeb & Co., Wall Street’s second-largest investment bank after J.P. Morgan. He didn’t hurt himself by marrying Alice Hanauer, the daughter of a firm partner. She was a Vassar graduate and artist who made pottery. Strauss became a firm partner at age 32 and would become immensely wealthy from investments, especially in the steel industry.

In 1938, after Kristallnacht in Germany, Strauss used his considerable contacts to implore congressional Republicans to allow 20,000 Jewish refugees to enter the United States. They declined, citing already high unemployment because of the continuing Great Depression.

When the United States entered World War II, Strauss first joined the U.S. Navy Reserve, then active duty. He held a desk job because of bad eyesight (his vision was impaired when he was 10 years old from a rock fight, probably with one of Richmond’s many neighborhood boy gangs). In 1945 Strauss was promoted from lieutenant commander to rear admiral. On July 16, 1945, the nuclear Trinity bomb was tested under the direction of Oppenheimer and Lt. Gen. Groves in New Mexico. President Harry F. Truman ordered bombs dropped on Japan soon thereafter.

In 1953 Strauss was appointed by President Eisenhower, whose campaigns he had supported generously, as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. He served until 1958. It was during this period that animus arose between Strauss and Oppenheimer over peacetime uses of atomic energy, specifically regarding the exportation of radioactive isotopes; Strauss was opposed. He became an advocate of peaceful uses of atomic energy by free enterprise. A die-hard, patriotic Republican, Strauss also believed that Oppenheimer had long-held leftist/socialist leanings. Seeing a potential threat to national security, after Strauss encouraged J. Edgar Hoover to investigate Oppenheimer, the physicist was denied federal security clearance. Their frayed relationship led to misery on both sides, as the second half of the film dramatizes.

In 1958 Eisenhower installed Strauss as secretary of commerce during a congressional recess. In 1959, having been nominated for a full appointment, Strauss underwent a long and humiliating hearing, and eventual defeat, for the post. Democratic senators had used their muscle before senatorial and presidential elections to thwart both Eisenhower and Strauss. Both Sens. John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson (two later presidents), voted against Strauss in a close contest.

So, at 70, Strauss retired to his 2,000-acre farm at Brandy Station near Culpeper, Virginia. It had 800 head of angus cattle and a mansion constructed of Virginia stone. There, he wrote two books (his memoir was a New York Times bestseller). He also continued his educational, medical, cultural and Jewish philanthropies (during his New York years he was president of the venerable Temple Emanu-El, a Reform congregation on Fifth Avenue). He also served as a trustee of the Metropolitan Opera.

Back in Virginia, he had terms as a trustee of Hampton Institute (now University), the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Virginia Historical Society (now the Virginia Museum of History & Culture). He donated funds to the Medical College of Virginia (now the VCU School of Medicine) for research in cancer and other related diseases. The Lewis Strauss Research Laboratory on the MCV campus at 527 N. 12th St. bears his name (it was in this facility that Dr. David Hume, whose team performed the world’s first successful kidney transplant at Harvard, continued his work, as did transplant pioneers Hyung Mo Lee and Richard Lower).

Both his parents had succumbed to cancer and in 1974, Strauss himself died of the disease. His funeral was at Temple Emanu-El in Manhattan and he is buried in Richmond’s Hebrew Cemetery at Fourth and Hospital streets.

In “Oppenheimer,” Robert Downey Jr. resurrects Strauss. According to The New Yorker, the actor provides “the most densely textured performance of his career…he all but commandeers the film.”

See it.

Correction: An earlier version of this column incorrectly state the address of Lewis Strauss’s childhood home in Richmond. It was 1142 West Ave.

Fascinating story. Strauss is a fine example of Richmond’s significant Jewish community and their contributions to Richmond.

Excellent article Ed. Thanks for your research and bringing this information forward.

Ed Slipek is the conscience of Richmond. Run for mayor, Eddie!

Beautifully written piece, thanks for the great research