“Irrigation Ditch” from the series In This Here Place, 2019, Dawoud Bey. Rennie Collection, Vancouver. Image © Dawoud Bey

Two intriguingly deep and perhaps wistful photography exhibitions are currently at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Both the monochromatic Dawoud Bey: Elegy installation and Willie Anne Wright: Artist and Alchemist, a career retrospective of inventive works by an iconic Virginia artist, offer contemporary takes on how the past and present collide to haunt historic places and psyches in the 21st century.

But these respective presentations, impeccably installed, feel like more than art exhibitions; they are like a symphony in Bey’s case, or in Wright’s evolution, a serious musical play.

Photographer Dawoud Bey was born in New York City in 1953, educated at Yale, received a coveted MacArthur Fellowship, and now teaches at Columbia College Chicago. Entitling his ambitious VMFA piece Elegy, museumgoers might expect a melancholy poem. Rather, a succession of galleries explode with something akin to an orchestral composition. The VMFA curator of modern and contemporary art, Valerie Cassel Oliver, organized the installation.

“Untitled (Trail and Trees)” from the series Stony the Road, 2023, Dawoud Bey. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Mrs. Alfred duPont, by exchange. Image © Dawoud Bey

The first gallery or “movement” offers the series Stony the Road, 2023, an opening visual sonata that sets the overall mood for the installation. Presented here are 12 gelatin silver print photos of the well-worn Richmond Slave Trail. The now-leaf-domed path extends for three miles along the Manchester riverfront. Bey imagines the untenable experience of enslavement by retracing the steps of men, women and children who were sold at auction here from 1830 to 1860. This segment’s title, Stony the Road, is a lyric from a long-beloved hymn, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

As visitors move to Elegy’s second space, they encounter the hypnotic sound film “350,000,” 2023. It honors the number of enslaved people who were force-walked on the Richmond route that followed the riverbank. The soundtrack, suggesting various intonations, heavy footsteps and deep breathing, was designed by E. Gaynell Sherrod, a dance and choreography professor at Virginia Commonwealth University. Collaborators were cinematographer Bron Moyi and local production companies Spang TV and In Your Ear Studios.

Next up is a third gallery with huge photographs, In This Here Place, 2019. Bey conjures the Black experience in antebellum Louisiana with his images of humble structures and landscapes at Evergreen plantation, perhaps the only Deep South plantation with extant slave cabins.

Finally, Bey’s inadvertent symphony concludes with photographs shot near Cleveland and Hudson, Ohio. With aching sharpness, he imagines pathways used by fugitives along the Underground Railroad. Here, as throughout Elegy, there is the aura of uncertainty but also glimmers of possibilities. Upon leaving Bey’s emotional opus, visitors can inscribe their thoughts on notecards. These introspective responses contain expressions of sadness as well as hope from having experienced the artists’ masterful manipulation of black and shades of gray in fraught places.

“Untitled (Curve in the Trail)” from the series Stony the Road, 2023, Dawoud Bey. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Mrs. Alfred duPont, by exchange. Image © Dawoud Bey

Willie Anne Wright, still an active artist at 99, was born in Richmond in 1924. She graduated from Thomas Jefferson High School. At the College of William & Mary she augmented her studies as a psychology major with art courses. One of the first images in Willie Anne Wright: Artist and Alchemist, which examines her 60-year career, is a painting of a restored brick house in Colonial Williamsburg. But Wright eschews a sunny postcard treatment in favor of an expressionistic approach with confident dark lines and a large tree that looms overhead ominously. Perhaps it was World War II, maybe her college studies, but she is not thinking of tricorne hats and Southern hospitality.

Wright went on to receive a fine arts degree from Richmond Professional Institute (now VCU) in the early 1960s while married with children. That she aggressively embraced the colors and vibe of the decade is apparent in two paintings that depict a household TV set with The Supremes on the screen. In the “Green Supremes,” 1969, the trio may be singing “Stop in the Name of Love,” but Wright has embraced the bold colorations of pop art. Think painters Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann and Alex Katz.

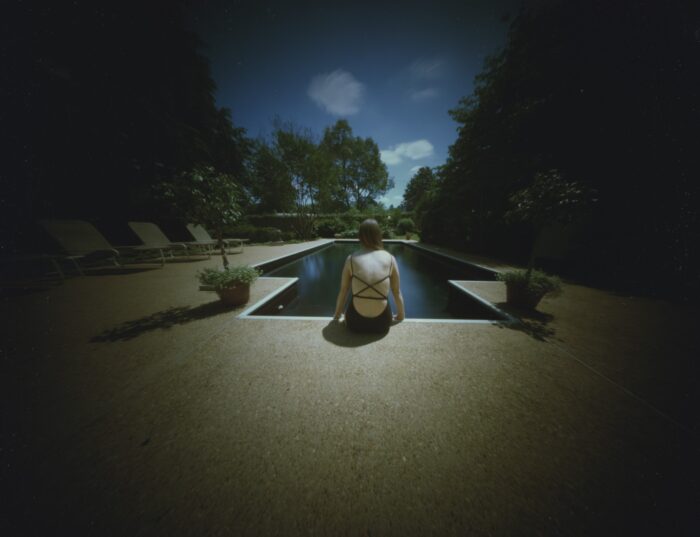

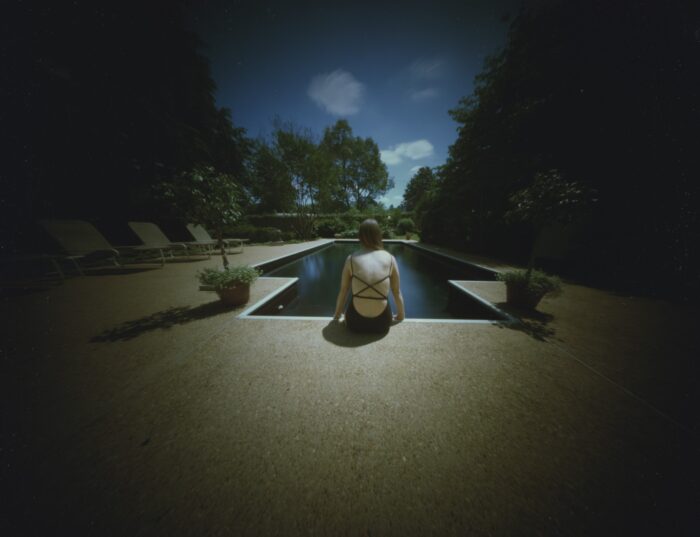

“Anne S at Jack B’s Pool (Back),” 1984, Willie Anne Wright. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2022.302

Always inventive, during the early 1970s Wright moved to photography and stumbled onto pinhole photography, eventually using a Cibachrome color process. Works from two of her series, “Civil War Redux” and “Southland,” reveal unique approaches to depicting Southern historicist themes. She was fascinated by Civil War reenactors and just as much by the visual ironies of the modern-day settings in which they operated. One photograph already looks inadvertently dated; it shows a reenactor portraying Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee with camp followers at the base of the Lee monument that once stood in the intersection of Monument and Allen avenues.

The fact that there are few nostalgic bones in Wright’s body is clear in her 1980s work when she shifted her camera’s gaze from reenactors to public beaches and private swimming pools. “Colonial Beach – Municipal Pier,” 1981, and “Anne S at Jack B’s Pool (Back),” 1984, are among her finest pieces. They are breathtakingly rich with photographic jewel-like tones and well-anchored composition. Other photographs and camera-less photograms (created later in her impressive repertory) add additional proof of Wright’s restless aesthetic explorations. These include more ethereal images suggesting Victorian-era sensitivities laced with expressions of feminist themes.

“Endlessly curious and experimental” is how the retrospective’s curator, Sarah Kennel, the museum’s curator of photography, describes her work. “Wright merges a deep interest in forms with a contemporary, irreverent sensibility.”

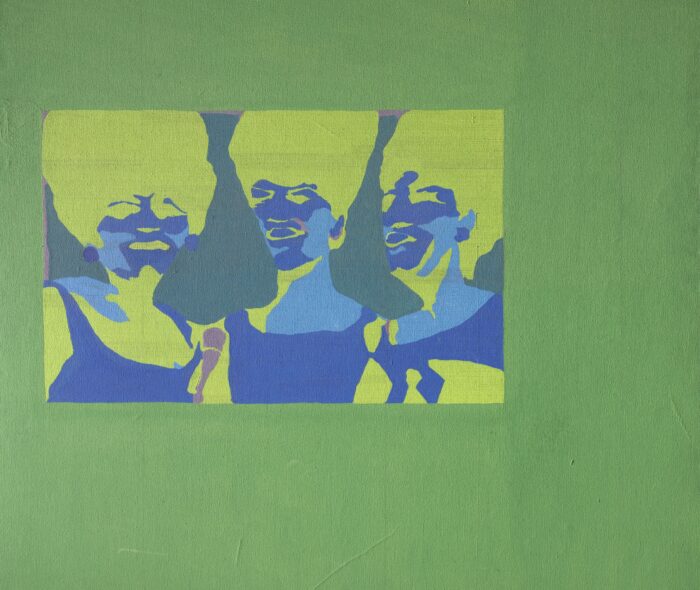

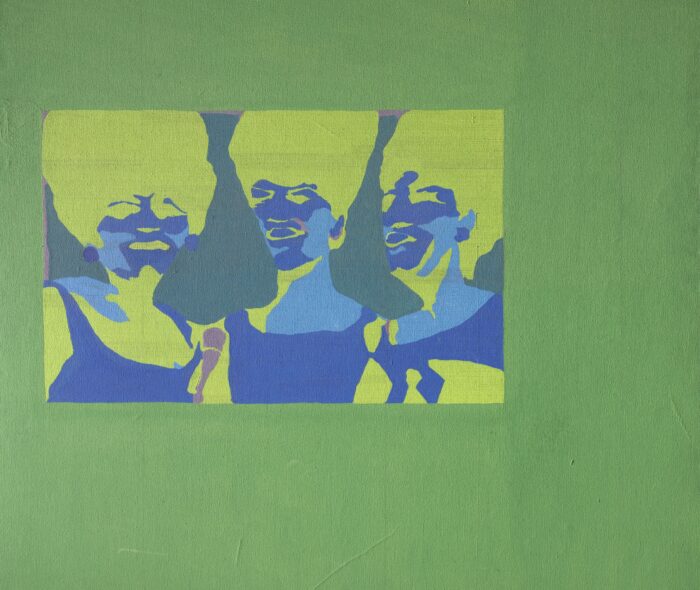

“Green Supremes,” 1969, Willie Anne Wright. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow

Endowment, 2022.246

If Bey’s VMFA installation is symphonic, Wright’s retrospective suggests “Candide,” a classic American musical. In composer Leonard Bernstein’s retelling of Voltaire’s novel, Candide embarks on a lifetime journey seeking truth and beauty. He finds that while we may not live in the best of all possible worlds, by melding past and present we can be informed to attempt the possible.

Dawoud Bey: Elegy, continues through Feb. 25. There is an admission fee that requires timed tickets. In conjunction with the installation, a VMFA symposium on Jan. 26 and 27, “Picturing the Black Racial Imaginary,” will feature leading scholars, writers, artists and community leaders.

Willie Anne Wright: Artist and Alchemist continues until April 28. In-depth, fully illustrated catalogs of each exhibition are available in the VMFA store.

“Irrigation Ditch” from the series In This Here Place, 2019, Dawoud Bey. Rennie Collection, Vancouver. Image © Dawoud Bey

Two intriguingly deep and perhaps wistful photography exhibitions are currently at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Both the monochromatic Dawoud Bey: Elegy installation and Willie Anne Wright: Artist and Alchemist, a career retrospective of inventive works by an iconic Virginia artist, offer contemporary takes on how the past and present collide to haunt historic places and psyches in the 21st century.

But these respective presentations, impeccably installed, feel like more than art exhibitions; they are like a symphony in Bey’s case, or in Wright’s evolution, a serious musical play.

Photographer Dawoud Bey was born in New York City in 1953, educated at Yale, received a coveted MacArthur Fellowship, and now teaches at Columbia College Chicago. Entitling his ambitious VMFA piece Elegy, museumgoers might expect a melancholy poem. Rather, a succession of galleries explode with something akin to an orchestral composition. The VMFA curator of modern and contemporary art, Valerie Cassel Oliver, organized the installation.

“Untitled (Trail and Trees)” from the series Stony the Road, 2023, Dawoud Bey. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Mrs. Alfred duPont, by exchange. Image © Dawoud Bey

The first gallery or “movement” offers the series Stony the Road, 2023, an opening visual sonata that sets the overall mood for the installation. Presented here are 12 gelatin silver print photos of the well-worn Richmond Slave Trail. The now-leaf-domed path extends for three miles along the Manchester riverfront. Bey imagines the untenable experience of enslavement by retracing the steps of men, women and children who were sold at auction here from 1830 to 1860. This segment’s title, Stony the Road, is a lyric from a long-beloved hymn, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

As visitors move to Elegy’s second space, they encounter the hypnotic sound film “350,000,” 2023. It honors the number of enslaved people who were force-walked on the Richmond route that followed the riverbank. The soundtrack, suggesting various intonations, heavy footsteps and deep breathing, was designed by E. Gaynell Sherrod, a dance and choreography professor at Virginia Commonwealth University. Collaborators were cinematographer Bron Moyi and local production companies Spang TV and In Your Ear Studios.

Next up is a third gallery with huge photographs, In This Here Place, 2019. Bey conjures the Black experience in antebellum Louisiana with his images of humble structures and landscapes at Evergreen plantation, perhaps the only Deep South plantation with extant slave cabins.

Finally, Bey’s inadvertent symphony concludes with photographs shot near Cleveland and Hudson, Ohio. With aching sharpness, he imagines pathways used by fugitives along the Underground Railroad. Here, as throughout Elegy, there is the aura of uncertainty but also glimmers of possibilities. Upon leaving Bey’s emotional opus, visitors can inscribe their thoughts on notecards. These introspective responses contain expressions of sadness as well as hope from having experienced the artists’ masterful manipulation of black and shades of gray in fraught places.

“Untitled (Curve in the Trail)” from the series Stony the Road, 2023, Dawoud Bey. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Mrs. Alfred duPont, by exchange. Image © Dawoud Bey

Willie Anne Wright, still an active artist at 99, was born in Richmond in 1924. She graduated from Thomas Jefferson High School. At the College of William & Mary she augmented her studies as a psychology major with art courses. One of the first images in Willie Anne Wright: Artist and Alchemist, which examines her 60-year career, is a painting of a restored brick house in Colonial Williamsburg. But Wright eschews a sunny postcard treatment in favor of an expressionistic approach with confident dark lines and a large tree that looms overhead ominously. Perhaps it was World War II, maybe her college studies, but she is not thinking of tricorne hats and Southern hospitality.

Wright went on to receive a fine arts degree from Richmond Professional Institute (now VCU) in the early 1960s while married with children. That she aggressively embraced the colors and vibe of the decade is apparent in two paintings that depict a household TV set with The Supremes on the screen. In the “Green Supremes,” 1969, the trio may be singing “Stop in the Name of Love,” but Wright has embraced the bold colorations of pop art. Think painters Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann and Alex Katz.

“Anne S at Jack B’s Pool (Back),” 1984, Willie Anne Wright. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2022.302

Always inventive, during the early 1970s Wright moved to photography and stumbled onto pinhole photography, eventually using a Cibachrome color process. Works from two of her series, “Civil War Redux” and “Southland,” reveal unique approaches to depicting Southern historicist themes. She was fascinated by Civil War reenactors and just as much by the visual ironies of the modern-day settings in which they operated. One photograph already looks inadvertently dated; it shows a reenactor portraying Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee with camp followers at the base of the Lee monument that once stood in the intersection of Monument and Allen avenues.

The fact that there are few nostalgic bones in Wright’s body is clear in her 1980s work when she shifted her camera’s gaze from reenactors to public beaches and private swimming pools. “Colonial Beach – Municipal Pier,” 1981, and “Anne S at Jack B’s Pool (Back),” 1984, are among her finest pieces. They are breathtakingly rich with photographic jewel-like tones and well-anchored composition. Other photographs and camera-less photograms (created later in her impressive repertory) add additional proof of Wright’s restless aesthetic explorations. These include more ethereal images suggesting Victorian-era sensitivities laced with expressions of feminist themes.

“Endlessly curious and experimental” is how the retrospective’s curator, Sarah Kennel, the museum’s curator of photography, describes her work. “Wright merges a deep interest in forms with a contemporary, irreverent sensibility.”

“Green Supremes,” 1969, Willie Anne Wright. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow

Endowment, 2022.246

If Bey’s VMFA installation is symphonic, Wright’s retrospective suggests “Candide,” a classic American musical. In composer Leonard Bernstein’s retelling of Voltaire’s novel, Candide embarks on a lifetime journey seeking truth and beauty. He finds that while we may not live in the best of all possible worlds, by melding past and present we can be informed to attempt the possible.

Dawoud Bey: Elegy, continues through Feb. 25. There is an admission fee that requires timed tickets. In conjunction with the installation, a VMFA symposium on Jan. 26 and 27, “Picturing the Black Racial Imaginary,” will feature leading scholars, writers, artists and community leaders.

Willie Anne Wright: Artist and Alchemist continues until April 28. In-depth, fully illustrated catalogs of each exhibition are available in the VMFA store.