A site plan of the proposed Bensley Agrihood project, which blended income-restricted homes with a working farm and education center. (County documents)

The future of a proposed farm-centric development in Chesterfield is in doubt as a local housing nonprofit alleges racial discrimination against a county supervisor and planning commissioner who it says refused to meet with black leaders involved in the project.

Maggie Walker Community Land Trust, which has been working with nonprofits Girls For A Change and Happily Natural Day on the proposed Bensley Agrihood project, issued a statement Thursday that it had withdrawn the group’s rezoning application after multiple deferrals by the Chesterfield Planning Commission to hear the case.

The statement, which was emailed and posted on MWCLT’s website, said the request was pulled “because it became clear — after 583 days — that the project would not receive rezoning approval due to a continuing legacy of zoning processes being used to discriminate against BIPOC land ownership.” The acronym BIPOC stands for “black, indigenous and people of color.”

The statement added that “zoning was used, as it has been historically, to attempt to enact covenants and arbitrary requirements that limit BIPOC land ownership and use” and referred to “instances of both elected and appointed officials in the Bermuda district refusing to meet with the Black leaders of GFAC and HND despite their expertise in urban farming and community programming…”

It said the group faced “questions about illegal substances being grown on the site,” a request for a detailed list of approved produce to be grown and restrictions on the use of a planned education center that would have been part of the development. It said the group was not willing to comply with the most recent requests, including replacing the farm with a community garden, because such changes were moving the project “outside of its intended purpose.”

“Accordingly, the project will not move forward in its current form, and the estimated $6.5M investment in affordable housing, education, job training, and community farming will be a loss for the community,” the statement said.

While the statement does not identify them, it refers to Bermuda District Supervisor Jim Ingle and Planning Commissioner Gib Sloan, who did not comment for this story.

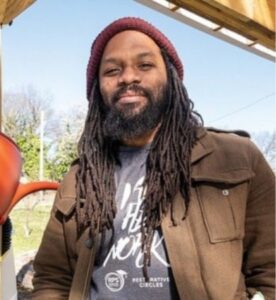

While MWCLT was the applicant on the case, CEO Erica Sims said in an interview Thursday that the project was driven by Angela Patton and Duron Chavis, the heads of Girls For A Change and Happily Natural Day, respectively, who she said had approached the land trust for the project.

When the meetings were held with the district’s supervisor and planning commissioner as well as county planning staff in light of the deferrals, Sims said that Patton and Chavis were not allowed to participate and that officials would meet only with MWCLT as the official applicant.

“We needed both Angela and Duron to be at meetings with county officials in order to answer their questions about the nature of the project – what are you going to do on this site, how is this going to be operated, what will you allow here and there,” Sims said. “We needed them to be there, but we were told that they would not be allowed at the meeting because they were not the technical applicant of record.”

Asked if she thought there was more to the decision than that explanation, Sims referred back to the land trust’s statement.

The statement is a rare public rebuke against government officials from MWCLT, which is Chesterfield’s designated land bank and has worked with the county on housing developments for lower-income residents such as Ettrick Landing, a 10-home subdivision it is building in southern Chesterfield.

In response to requests for comment from Ingle and County Administrator Joe Casey, Chesterfield provided a statement to BizSense that was said to be on behalf of county officials and staff. It said the county “is proud of the partnership that’s been built” with MWCLT and noted the time that officials and planning staff have spent on the case “through community meetings and conversations with the applicant.”

“As with all rezoning requests, there is a standard process that requires a variety of steps be taken before a project can be approved,” the county’s statement said. “Sometimes, the process ends with applications being withdrawn by the applicant. During the course of the Bensley Agrihood process, county officials and staff worked through a number of recommendations with MWCLT.

“We disagree with the recent statement posted to the MWCLT website,” the county said, adding later in the statement: “The concerns from county officials were strictly over the impacts on the surrounding residential neighborhoods that needed to be considered, including crowd concerns related to events and commercial traffic as well as commercial use within a residential area.”

As originally proposed, the project was to include 14 detached income-restricted homes, four of those so-called “tiny homes,” a working farm, and a building for community-oriented classes. The development would have filled a 7-acre site at 2600 Swineford Road, just west of Route 1 and a few blocks south of Chippenham Parkway.

Called an agrihood, defined as a residential community with a farm or community garden as a central amenity, Bensley Agrihood was pitched as helping to meet housing and food needs in that area, which a project website describes as a “food desert” and racially diverse. The project was awarded a $200,000 planning grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, according to the website.

The land is owned by Marcia Woodley and permitted by the county for a stock farm with livestock such as goats and donkeys. The Bensley Agrihood farm was to be operated by Happily Natural, described as a “racial, climate, and food justice” advocate, and the education building was to be operated by Girls For A Change, whose CEO, Patton, lives next door to the project site.

Sims said Patton approached the land trust with the idea for the project, and MWCLT had a contract with Woodley to purchase the site. Sims said Thursday that the land trust was in the process of terminating that contract but that Happily Natural still plans to work with Woodley to establish an urban farm there.

Happily Natural’s Chavis said the project had been supported in the community and received support letters from Virginia State University’s Small Farm Outreach Program, Virginia Tech’s Center for Food Systems and Community Transformation, Foodshed Capital and nearby Bensley Elementary School. County planning staff also recommended approving the project.

Chavis said he and Patton initially met with Commissioner Sloan and Supervisor Ingle when the project was first proposed. He said he didn’t understand why they were not allowed in subsequent meetings and said he should have been permitted not only because of his work on the project but as a member of MWCLT’s board.

“A lot of (Sloan’s) issues related to the farm. We were like, let’s have a conversation, let’s get in a meeting, and he was just refusing, essentially, to meet with us,” Chavis said. “Him specifically denying me from coming to the meeting was really odd, because he was willing to meet with Maggie Walker; he just didn’t want me to be in the room.

“It was really a disturbing situation,” he said, adding that Sloan had asked in emails whether they were going to illegally grow cannabis on the property. “Just odd stuff that just doesn’t add up in relation to the other people that are farming in the county.

“At the core of it, it’s an example of how zoning laws can be used by an individual in county leadership to block projects without any legitimate reason why,” he said. “We just have to figure out an alternative way to make the project happen, and we’re currently exploring what that looks like now.”

The project’s website includes a post from Chavis on X, formerly Twitter, about the 2022 planning grant award. The top of the post displays Chavis’s profile name: Son of a Dope Dealer.

Asked if the profile name could have contributed to the questions and deferrals, Chavis was dismissive.

“I don’t sell narcotics. I have a legitimate business in nonprofits,” he said. “My father chose that route for his life, and that has absolutely nothing to do with the work that I do in the community.”

Sloan did not respond to a call and email seeking comment Thursday. Ingle deferred to the statement from the county. BizSense also reached out to Patton, who did not return a call for comment.

At the Planning Commission’s May meeting, when the case was deferred a fourth time since it was first on the docket in January, Sloan said the planning department had received “numerous emails and phone calls” in support of the deferral.

“Many folks in the community are asking for us to come back out to the community to provide an update once we receive updated proffers from the applicant,” Sloan said.

Meanwhile, a group supporting the Bensley Agrihood project has scheduled a “speak out” event at the project site to rally support for the project and “share its experience negotiating with Chesterfield County’s Board of Supervisors during the rezoning process.” The rally is scheduled Sunday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

A site plan of the proposed Bensley Agrihood project, which blended income-restricted homes with a working farm and education center. (County documents)

The future of a proposed farm-centric development in Chesterfield is in doubt as a local housing nonprofit alleges racial discrimination against a county supervisor and planning commissioner who it says refused to meet with black leaders involved in the project.

Maggie Walker Community Land Trust, which has been working with nonprofits Girls For A Change and Happily Natural Day on the proposed Bensley Agrihood project, issued a statement Thursday that it had withdrawn the group’s rezoning application after multiple deferrals by the Chesterfield Planning Commission to hear the case.

The statement, which was emailed and posted on MWCLT’s website, said the request was pulled “because it became clear — after 583 days — that the project would not receive rezoning approval due to a continuing legacy of zoning processes being used to discriminate against BIPOC land ownership.” The acronym BIPOC stands for “black, indigenous and people of color.”

The statement added that “zoning was used, as it has been historically, to attempt to enact covenants and arbitrary requirements that limit BIPOC land ownership and use” and referred to “instances of both elected and appointed officials in the Bermuda district refusing to meet with the Black leaders of GFAC and HND despite their expertise in urban farming and community programming…”

It said the group faced “questions about illegal substances being grown on the site,” a request for a detailed list of approved produce to be grown and restrictions on the use of a planned education center that would have been part of the development. It said the group was not willing to comply with the most recent requests, including replacing the farm with a community garden, because such changes were moving the project “outside of its intended purpose.”

“Accordingly, the project will not move forward in its current form, and the estimated $6.5M investment in affordable housing, education, job training, and community farming will be a loss for the community,” the statement said.

While the statement does not identify them, it refers to Bermuda District Supervisor Jim Ingle and Planning Commissioner Gib Sloan, who did not comment for this story.

While MWCLT was the applicant on the case, CEO Erica Sims said in an interview Thursday that the project was driven by Angela Patton and Duron Chavis, the heads of Girls For A Change and Happily Natural Day, respectively, who she said had approached the land trust for the project.

When the meetings were held with the district’s supervisor and planning commissioner as well as county planning staff in light of the deferrals, Sims said that Patton and Chavis were not allowed to participate and that officials would meet only with MWCLT as the official applicant.

“We needed both Angela and Duron to be at meetings with county officials in order to answer their questions about the nature of the project – what are you going to do on this site, how is this going to be operated, what will you allow here and there,” Sims said. “We needed them to be there, but we were told that they would not be allowed at the meeting because they were not the technical applicant of record.”

Asked if she thought there was more to the decision than that explanation, Sims referred back to the land trust’s statement.

The statement is a rare public rebuke against government officials from MWCLT, which is Chesterfield’s designated land bank and has worked with the county on housing developments for lower-income residents such as Ettrick Landing, a 10-home subdivision it is building in southern Chesterfield.

In response to requests for comment from Ingle and County Administrator Joe Casey, Chesterfield provided a statement to BizSense that was said to be on behalf of county officials and staff. It said the county “is proud of the partnership that’s been built” with MWCLT and noted the time that officials and planning staff have spent on the case “through community meetings and conversations with the applicant.”

“As with all rezoning requests, there is a standard process that requires a variety of steps be taken before a project can be approved,” the county’s statement said. “Sometimes, the process ends with applications being withdrawn by the applicant. During the course of the Bensley Agrihood process, county officials and staff worked through a number of recommendations with MWCLT.

“We disagree with the recent statement posted to the MWCLT website,” the county said, adding later in the statement: “The concerns from county officials were strictly over the impacts on the surrounding residential neighborhoods that needed to be considered, including crowd concerns related to events and commercial traffic as well as commercial use within a residential area.”

As originally proposed, the project was to include 14 detached income-restricted homes, four of those so-called “tiny homes,” a working farm, and a building for community-oriented classes. The development would have filled a 7-acre site at 2600 Swineford Road, just west of Route 1 and a few blocks south of Chippenham Parkway.

Called an agrihood, defined as a residential community with a farm or community garden as a central amenity, Bensley Agrihood was pitched as helping to meet housing and food needs in that area, which a project website describes as a “food desert” and racially diverse. The project was awarded a $200,000 planning grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, according to the website.

The land is owned by Marcia Woodley and permitted by the county for a stock farm with livestock such as goats and donkeys. The Bensley Agrihood farm was to be operated by Happily Natural, described as a “racial, climate, and food justice” advocate, and the education building was to be operated by Girls For A Change, whose CEO, Patton, lives next door to the project site.

Sims said Patton approached the land trust with the idea for the project, and MWCLT had a contract with Woodley to purchase the site. Sims said Thursday that the land trust was in the process of terminating that contract but that Happily Natural still plans to work with Woodley to establish an urban farm there.

Happily Natural’s Chavis said the project had been supported in the community and received support letters from Virginia State University’s Small Farm Outreach Program, Virginia Tech’s Center for Food Systems and Community Transformation, Foodshed Capital and nearby Bensley Elementary School. County planning staff also recommended approving the project.

Chavis said he and Patton initially met with Commissioner Sloan and Supervisor Ingle when the project was first proposed. He said he didn’t understand why they were not allowed in subsequent meetings and said he should have been permitted not only because of his work on the project but as a member of MWCLT’s board.

“A lot of (Sloan’s) issues related to the farm. We were like, let’s have a conversation, let’s get in a meeting, and he was just refusing, essentially, to meet with us,” Chavis said. “Him specifically denying me from coming to the meeting was really odd, because he was willing to meet with Maggie Walker; he just didn’t want me to be in the room.

“It was really a disturbing situation,” he said, adding that Sloan had asked in emails whether they were going to illegally grow cannabis on the property. “Just odd stuff that just doesn’t add up in relation to the other people that are farming in the county.

“At the core of it, it’s an example of how zoning laws can be used by an individual in county leadership to block projects without any legitimate reason why,” he said. “We just have to figure out an alternative way to make the project happen, and we’re currently exploring what that looks like now.”

The project’s website includes a post from Chavis on X, formerly Twitter, about the 2022 planning grant award. The top of the post displays Chavis’s profile name: Son of a Dope Dealer.

Asked if the profile name could have contributed to the questions and deferrals, Chavis was dismissive.

“I don’t sell narcotics. I have a legitimate business in nonprofits,” he said. “My father chose that route for his life, and that has absolutely nothing to do with the work that I do in the community.”

Sloan did not respond to a call and email seeking comment Thursday. Ingle deferred to the statement from the county. BizSense also reached out to Patton, who did not return a call for comment.

At the Planning Commission’s May meeting, when the case was deferred a fourth time since it was first on the docket in January, Sloan said the planning department had received “numerous emails and phone calls” in support of the deferral.

“Many folks in the community are asking for us to come back out to the community to provide an update once we receive updated proffers from the applicant,” Sloan said.

Meanwhile, a group supporting the Bensley Agrihood project has scheduled a “speak out” event at the project site to rally support for the project and “share its experience negotiating with Chesterfield County’s Board of Supervisors during the rezoning process.” The rally is scheduled Sunday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

From the article, it seems to me like it’s zoned for agriculture and residential… that’s all that the county should need to know. What they farm/grow, is a legal enforcement issue, not a zoning issue. Many farms have adapted to education centers, farm stands, and agri-tourism to help supplement the difficult farm career.

I get the education questions to some degree as this is an older suburb surrounded by SF residential. Residents, through comments to staff and their BOS rep might have asked questions like how large, how many students, what about bus traffic, etc….I think they could have valid questions but I agree what are you going to grow and not wanting to meet with other team members of the project. I am sure the non-profit and MWLT have some form of a formal agreement. I know C-field, in doing rezones as conditions of a sale of land, has had meetings with… Read more »

What a tremendous loss for the County, our region needed affordable housing 583 days ago and we need it even more now. The project is also incredibly inventive, such a shame this couldn’t move forward.

Black, indigenous…

Just say what you mean:

Anyone but white.

No whites.

Got it!

This is unbelievable that government officials can hide behind a thin veil to question the impacts a farm, a community-education center, and 14 affordable homes will have on the surrounding area. I think it’s completely logical to conclude that “We’re concerned about crowds” is being taken as discrimination when the zoning and community supports the project. On top of that trying to use Mr. Chavis’ social media handle to cast aspersions is absurd. What a tragic loss to the community and the country. We need more projects like this and more organizations like these across the country that have the… Read more »