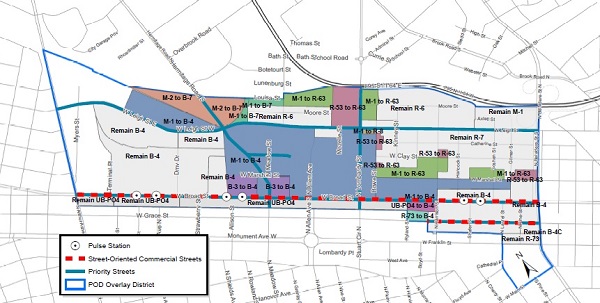

An aerial view of the area that’s the focus of this phase, generally north of Broad Street to the railroad tracks and between Lombardy Street and Arthur Ashe Boulevard. Courtesy City of Richmond.

Proposed zoning changes to allow denser development in the area across Broad Street from the Fan are moving forward despite opposition from neighbors that has been lingering for months.

The Richmond Planning Commission on Tuesday endorsed city-initiated proposals that would facilitate a third phase of rezonings recommended in the city’s Pulse Corridor Plan, the 2017 document that city planners are using to guide development in the area of the GRTC Pulse bus-rapid-transit line.

The proposed changes, which the City Council is expected to vote on next week, focus on land primarily north of Broad Street in and around the Carver and Newtowne West neighborhoods, generally between Belvidere Street and the DMV headquarters building. The primarily manufacturing-zoned properties also include parcels between Leigh Street and the railroad tracks in the area of Hermitage Road and Lombardy Street.

Most of the properties would be rezoned to B-4 or B-7 business designations, while others along Lombardy and in Carver would change to multifamily residential zonings that allow for higher densities and more variety of uses.

The proposed changes to B-4 on the north side of Broad Street have been a point of concern for area residents and neighborhood groups south of Broad, many of whom have expressed opposition to the rezonings since they were introduced to the council this spring.

Opponents noted the change would allow for taller building heights than the 12 stories currently allowed, in some places potentially upward of 20 stories. They also questioned the timing of the proposals in the midst of a pandemic, contending that adequate public notice and awareness was not achievable.

The opposition prompted planners to delay the process for months, allowing for more outreach that culminated with a virtual forum last Thursday.

But opposition remained by the time of the commission’s meeting, with about a dozen residents in the area sending emails in recent days and several speakers voicing concerns in Tuesday’s public hearing, including representatives of the Fan District Association, Historic Richmond Foundation and Partnership for Smarter Growth.

The proposals had received some letters of support as well, including from developer UrbanCore Construction and Sauer Properties, possibly the largest landowner affected with 36 acres in the area of Broad Street, Hermitage Road and West Marshall Street, including its Whole Foods-anchored Sauer Center.

Ashley Peace, Sauer Properties’ president, spoke in the hearing about how the changes would allow for “something extraordinary” with its land, referring to a master planning process underway for further development that she said would include medium- to high-density uses including office and residential.

Commissioners ended up backing the changes, which would replace existing zoning that city planner Anne Darby said, “is not appropriate for a growing, land-locked city.”

Darby said most of that zoning was put in place in 1976 and noted population projections from more than 230,000 last year to as much as 340,000 by 2037, depending on how many families with children are living in the city.

Commissioners agreed that the denser development to come from the rezonings would accommodate more residential units not only to meet such projections but also to replace aging housing stock.

Commissioner Dave Johannas said the city will need to add up to 3,000 units a year to keep pace with population growth.

In accordance with the Pulse Corridor Plan, the changes also would encourage mixed-use development in the area of each Pulse station that blends housing, employment and entertainment, walking and cycling options, historic preservation and general connectivity.

Involved in this round of rezonings are the Science Museum, Allison Street and VCU & VUU stations.

The plan also encourages urban design elements such as smaller setbacks between buildings and streets, variety in building facades and screened parking.

But it was the added building height allowed in the proposed B-4 zoning that remained a point of contention for opponents. The existing B-4 district has no height restrictions, instead using an “inclined plane,” four-to-one ratio method to regulate building height and design.

The approach allows for a structure to go up 4 feet for every 1 foot in width from the center of adjacent right-of-way. In the case of Broad Street, Planning Director Mark Olinger confirmed that the result could potentially reach or exceed 20 stories in places such as in front of the Lowe’s Home Improvement and Kroger stores, at Sauer Center and around the DMV building.

Johannas reiterated that such heights would only be possible in some places, as opposed to what he described as opponents’ fears of “a half-canyon of large-scale high-rises.” Johannas said such heights would come with significant costs to developers, who he said would likely aim more for density over height.

Areas proposed to change from manufacturing to B-4 include the site of a 12-story tower planned at Broad and Lombardy. That project, by Minnesota-based Opus Group, was proposed earlier this year and approved based in large part on the expectation that zoning allowing the height was on its way along the corridor.

In its application, Opus had referred specifically to the city’s TOD-1 “transit-oriented development” district, which was introduced along Broad near Scott’s Addition in the first phase of Pulse-driven rezonings. A second phase focused on changing the bulk of Monroe Ward to TOD-1 and B-4.

This latest round of changes had initially proposed TOD-1 for a stretch of street-facing properties on the south side of Broad, from Ryland Street to Arthur Ashe Boulevard. But concerns from the West Grace Street Association prompted staff to remove those changes from the proposals endorsed Tuesday.

Another cluster of properties south of Broad, all in the block north of Grace Street between Ryland and Harrison streets, would be zoned B-4, bringing them in line with other properties to the east and removing them from an overlay district that requires off-street parking spaces.

In addition to the zoning changes, the proposals endorsed Tuesday would create an overlay district for the area and designate certain streets as street-oriented commercial and priority streets. Other properties within the overlay district not slated for rezoning would retain their current zoning for the time being, in keeping with recommendations in the Richmond 300 draft master plan update.

The city expects the rezonings associated with the Pulse Corridor Plan ultimately will create $1 billion in new assessed value in the next 20 years.

The City Council is scheduled to decide on the rezonings at its regular meeting Monday.

An aerial view of the area that’s the focus of this phase, generally north of Broad Street to the railroad tracks and between Lombardy Street and Arthur Ashe Boulevard. Courtesy City of Richmond.

Proposed zoning changes to allow denser development in the area across Broad Street from the Fan are moving forward despite opposition from neighbors that has been lingering for months.

The Richmond Planning Commission on Tuesday endorsed city-initiated proposals that would facilitate a third phase of rezonings recommended in the city’s Pulse Corridor Plan, the 2017 document that city planners are using to guide development in the area of the GRTC Pulse bus-rapid-transit line.

The proposed changes, which the City Council is expected to vote on next week, focus on land primarily north of Broad Street in and around the Carver and Newtowne West neighborhoods, generally between Belvidere Street and the DMV headquarters building. The primarily manufacturing-zoned properties also include parcels between Leigh Street and the railroad tracks in the area of Hermitage Road and Lombardy Street.

Most of the properties would be rezoned to B-4 or B-7 business designations, while others along Lombardy and in Carver would change to multifamily residential zonings that allow for higher densities and more variety of uses.

The proposed changes to B-4 on the north side of Broad Street have been a point of concern for area residents and neighborhood groups south of Broad, many of whom have expressed opposition to the rezonings since they were introduced to the council this spring.

Opponents noted the change would allow for taller building heights than the 12 stories currently allowed, in some places potentially upward of 20 stories. They also questioned the timing of the proposals in the midst of a pandemic, contending that adequate public notice and awareness was not achievable.

The opposition prompted planners to delay the process for months, allowing for more outreach that culminated with a virtual forum last Thursday.

But opposition remained by the time of the commission’s meeting, with about a dozen residents in the area sending emails in recent days and several speakers voicing concerns in Tuesday’s public hearing, including representatives of the Fan District Association, Historic Richmond Foundation and Partnership for Smarter Growth.

The proposals had received some letters of support as well, including from developer UrbanCore Construction and Sauer Properties, possibly the largest landowner affected with 36 acres in the area of Broad Street, Hermitage Road and West Marshall Street, including its Whole Foods-anchored Sauer Center.

Ashley Peace, Sauer Properties’ president, spoke in the hearing about how the changes would allow for “something extraordinary” with its land, referring to a master planning process underway for further development that she said would include medium- to high-density uses including office and residential.

Commissioners ended up backing the changes, which would replace existing zoning that city planner Anne Darby said, “is not appropriate for a growing, land-locked city.”

Darby said most of that zoning was put in place in 1976 and noted population projections from more than 230,000 last year to as much as 340,000 by 2037, depending on how many families with children are living in the city.

Commissioners agreed that the denser development to come from the rezonings would accommodate more residential units not only to meet such projections but also to replace aging housing stock.

Commissioner Dave Johannas said the city will need to add up to 3,000 units a year to keep pace with population growth.

In accordance with the Pulse Corridor Plan, the changes also would encourage mixed-use development in the area of each Pulse station that blends housing, employment and entertainment, walking and cycling options, historic preservation and general connectivity.

Involved in this round of rezonings are the Science Museum, Allison Street and VCU & VUU stations.

The plan also encourages urban design elements such as smaller setbacks between buildings and streets, variety in building facades and screened parking.

But it was the added building height allowed in the proposed B-4 zoning that remained a point of contention for opponents. The existing B-4 district has no height restrictions, instead using an “inclined plane,” four-to-one ratio method to regulate building height and design.

The approach allows for a structure to go up 4 feet for every 1 foot in width from the center of adjacent right-of-way. In the case of Broad Street, Planning Director Mark Olinger confirmed that the result could potentially reach or exceed 20 stories in places such as in front of the Lowe’s Home Improvement and Kroger stores, at Sauer Center and around the DMV building.

Johannas reiterated that such heights would only be possible in some places, as opposed to what he described as opponents’ fears of “a half-canyon of large-scale high-rises.” Johannas said such heights would come with significant costs to developers, who he said would likely aim more for density over height.

Areas proposed to change from manufacturing to B-4 include the site of a 12-story tower planned at Broad and Lombardy. That project, by Minnesota-based Opus Group, was proposed earlier this year and approved based in large part on the expectation that zoning allowing the height was on its way along the corridor.

In its application, Opus had referred specifically to the city’s TOD-1 “transit-oriented development” district, which was introduced along Broad near Scott’s Addition in the first phase of Pulse-driven rezonings. A second phase focused on changing the bulk of Monroe Ward to TOD-1 and B-4.

This latest round of changes had initially proposed TOD-1 for a stretch of street-facing properties on the south side of Broad, from Ryland Street to Arthur Ashe Boulevard. But concerns from the West Grace Street Association prompted staff to remove those changes from the proposals endorsed Tuesday.

Another cluster of properties south of Broad, all in the block north of Grace Street between Ryland and Harrison streets, would be zoned B-4, bringing them in line with other properties to the east and removing them from an overlay district that requires off-street parking spaces.

In addition to the zoning changes, the proposals endorsed Tuesday would create an overlay district for the area and designate certain streets as street-oriented commercial and priority streets. Other properties within the overlay district not slated for rezoning would retain their current zoning for the time being, in keeping with recommendations in the Richmond 300 draft master plan update.

The city expects the rezonings associated with the Pulse Corridor Plan ultimately will create $1 billion in new assessed value in the next 20 years.

The City Council is scheduled to decide on the rezonings at its regular meeting Monday.

I’m glad they are up zoning along Board Street it seems like a lot of Board Street is wasted space the form of poorly set up parking lots.

The other issue though is the City needs to ban wood frame construction that is 5 and 6 stories and even 8 stories tall and replace it with concerte and steel.

“Are you taking the Pulse to have a drink at Tarrants?”

Yes. In fact I regularly do exactly this now. It only takes about 5 minutes longer than driving and the car can stay safely at home.

I thought wood-frame construction was currently limited to 6 floors? Though, that may stack if placed on concrete/steel lower floors.

Hi Jackson. The idea of transit oriented zoning and development is to encourage people to live and work near transit and create more walkable and bikable neighborhoods in the process. The goal is to reduce car use which has been shown to have very serious environmental and public health impacts. I have lived my whole life within US car culture too, so I can see that changing it can seem like a fantasy, as you put it, but these kinds of decisions really do help. Cities across the globe demonstrate the efficacy of this model: linking transit to high density… Read more »