Recently approved changes to a decades-old program that has helped fuel redevelopment in Richmond through partial real estate tax abatements have some developers and builders who do business in the city on edge.

Richmond City Council last month adopted an ordinance repealing the partial tax exemption for rehabilitated structures, replacing it with a new program that would apply the abatements only to projects that include income-based housing units, with the goal of incentivizing income-based, or “affordable,” housing.

The change, which would take effect July 1, was approved at council’s Jan. 27 meeting as part of its consent agenda, in which business considered routine or non-controversial is lumped together and voted on at once. Council members Ellen Robertson, Michael Jones and President Cynthia Newbille were patrons on the bill.

Under the new program, abatements would be awarded only to multifamily and single-family residential rehabs with at least 30 percent of units set aside for residents making 80 percent or less of the area median income – currently $83,200 in Richmond’s metropolitan statistical area.

Commercial and industrial structures no longer would be eligible, and commercial space in residential mixed-use projects would not be counted in an abatement.

Qualifying structures must be 20 years old and “substantially rehabilitated” within two years of a building permit being issued or application received. Abatements would last up to 15 years and be equal to the increase in assessed property value resulting from the rehab. Traditionally, properties have been required to increase in value at least 40 percent to qualify for the program.

The changes follow recommendations from a 2019 study that the city commissioned from VCU’s Center for Urban and Regional Analysis. They also fall in line with a push to encourage more income-based housing in the city, a la Mayor Levar Stoney’s goal of creating 1,500 affordable housing units by 2023 and initiatives to transition residents from public housing to mixed-income housing.

Study advised changes

The CURA study, which cost the city about $52,000, was requested by city assessor Richie McKeithen, who came on in 2017 after stints in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. McKeithen, who previously worked for Richmond as a deputy assessor in the early 2000s, said he suggested taking a look at the program after council members asked what he thought the department could be doing better.

Noting the program dated back to the 1990s, McKeithen said it had remained largely unchanged despite economic shifts, save for a revision in 2007 that shortened the abatement period from 15 to 10 years, and to seven years for commercial properties outside the city’s enterprise zones. The program also was reviewed in 2013 to address a loophole of sorts regarding additions to structures.

With the study, which CURA conducted in 2018 and submitted in February 2019, McKeithen said: “One of their recommendations was (that) the city is running to a point where you don’t need to continue to give out the program the way you’re doing it now, but you’re having an affordable housing problem, so why don’t you give the program and the incentive to projects that relate to affordable housing.

“Several of the council people had already had a suggestion like that or had thought along those lines,” McKeithen said.

Douglas Dunlap, the city’s housing and community development director, whose department also is involved in the changes, noted the study found that the roughly 1,900 properties that participated in the program between 2009 and 2016 were concentrated in the city’s higher-income areas or stronger housing submarkets. While the program had been used across the city, the study found, poorer neighborhoods with weaker markets had been using it less.

The study also found that the amount of real estate tax revenue foregone due to the abatements during roughly the same period, from 2010 to 2017, totaled over $32 million that otherwise would have added to the city’s coffers.

“It really just substantiated the fact that the individuals who have benefited from the program over the last 10 years or more have primarily been individuals who would have done those projects regardless of whether they were receiving the benefit or not,” Dunlap said.

“The program was used initially to spur development in areas across the city, especially in those areas where we had experienced a period of disinvestment,” he said. “That CURA report really takes into account where we are right now, who’s actually benefiting from the program, (and) confirms that it’s being used on projects in neighborhoods that essentially would be able to afford and would move forward regardless of whether the tax benefit was available or not.

“We are now looking at that as an essential tool, along with other subsidies, to incentivize and continue to expand the supply of affordable units across the city. That’s where we have the greatest need, so that’s where the program will be focused,” Dunlap said.

The amount of tax revenue foregone, and the locations of abatement projects, were points that council member Jones emphasized this week during deliberations about the Navy Hill redevelopment plan that council ultimately voted down. The study found that most abatement projects are single-family rehabs, though the largest share in abatement value had been going to multifamily projects.

City Council member Michael Jones at Monday’s meeting. Jones referenced the abatement program during discussions on the Navy Hill project. (Jonathan Spiers)

“The one thing I’ve heard over is that tax dollars ought not go to private development, but no one is yelling about the tax abatement program,” Jones said at Monday’s council meeting, contending that it has primarily supported individual homes in city districts, including the West End, Northside, Scott’s Addition and Church Hill.

“Individuals want to know why we can’t fund schools; it’s because we have built communities, and not just for communities that are diverse, but for affluent individuals who can afford to pay property taxes,” Jones said.

“For over two and a half years I’ve asked for this study to be done, to look at how we have funded affluent Richmond,” he said. “… You want to build schools? We’re building three. You want to do building maintenance? We don’t have the money to do it, because we’ve built up Scott’s Addition, we’ve built up the Fan, we’ve built up Church Hill to where my grandmother can’t even move back into a house she owned.”

Developers concerned

While the ordinance, which council had continued for over a year, was approved in January with no discussion, it has generated response from Richmond’s development community. Some say the approval went unnoticed and the pending changes are unknown to many who do business and invest in Richmond.

At a council committee meeting last month where the changes were recommended, local developer David Cooley voiced support for keeping the current program going. He was the sole speaker in a public hearing on the ordinance.

“The program is one that has encouraged the restoration, the saving of old houses,” said Cooley, co-founder of Restoration Builders of Virginia.

“I’m fine with tacking the low-income concept onto this incentive program; I’m just standing up in favor of the real estate abatement program that’s currently in place for saving old houses,” he said. “I think it incentivizes us as developers, one more incentive which is needed, to take an old structure and give it new life.”

Danna Markland, CEO of the Home Building Association of Richmond, said she is concerned that a large segment of businesses active in the city has no idea the changes were approved and are coming.

She said the ordinance advanced despite requests from the group’s Multifamily Housing Council and city administrators for more time to negotiate program specifics. She said McKeithen proposed the changes to be relieved of the burden of administering the program, and that many in the homebuilding industry found several of the study’s recommendations problematic.

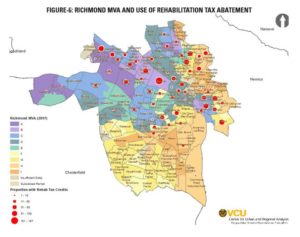

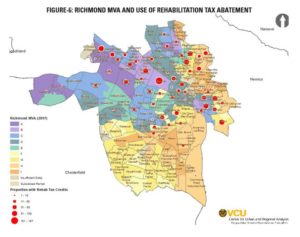

A map showing the study’s market value analysis of Richmond neighborhoods in relation to program use. (Courtesy VCU CURA)

“Measure the proven track record of the tax abatement against Richmond’s population growth and renaissance since the 1990s. It was the best economic development tool to drive investment citywide,” Markland said in an email.

“Rehabilitation projects are inherently cost-prohibitive. The substantial changes to the partial real estate tax abatement has developers questioning their ability to see current projects through to completion,” she said. “This regressive revocation of its single-family, multifamily and commercial tools will leave a large part of remaining inventory on the table while developers look for other communities where there is land available without structural barriers.”

Brian White, of local development firm Historic Housing and Main Street Realty, likewise said that the changes would result in developers and builders – as well as homeowners – moving away from the city in favor of the counties.

“We have a far higher tax rate than any of the surrounding (localities), and that’s understandable; the city’s got different needs, different realities than what the counties are dealing with,” he said. “But in order to encourage people to invest and pay those, we’re going to need to be creative in attracting some opportunities.

“I just think it’s critically important that we keep the real estate tax abatement in place. It’s been an undeniably powerful driver in rebuilding investment in the city that was fleeing, as if the place was on fire, for a long time,” White said. “I really think this should be a program that gets kept, while you can supplement it with efforts to spur affordable housing. I think that would be a good idea. But to get rid of this is not in the city’s best interest.”

White said Historic Housing, founded by his father David White and Louis Salomonsky, uses the program on about 80 percent of its projects, which are largely historic rehabs for multifamily housing. He said notable rehabs from other developers, such as Ron Stalling’s revival of The Hippodrome Theater and Ted Ukrop’s Quirk Hotel, likely would not have been possible without the program.

“These are real assets to the city and the community,” White said. “If people are not going to reinvest in these buildings, it just seems like a mistake to me.”

White said the investment that resulted from the incentive has contributed greatly to the city’s tax base, the assessed value of which he said has more than doubled over the past 20 years.

“Almost all of the properties that have used this program to help make it possible to reinvest in the city are fully taxable now. The abatements have expired,” he said. “They’re getting a whole lot more money from real estate taxes because of this program.”

White said he’s hopeful that the changes can be tweaked to preserve the current incentive before they take effect in July. He said he plans to reach out to as many council members as he can in the meantime.

“I don’t know what to expect,” he said. “I hope I can demonstrate to them how valuable it has been and continues to be for the city of Richmond.”

Dunlap said the city hasn’t received pushback to the changes as of yet. McKeithen said he’s aware of some concerns with the program but that he hasn’t heard from anyone directly.

“I heard there was some disgruntlement, but how can you argue with the study?” McKeithen said. “That’s why I wanted a study done, by a reputable group, so the facts are the facts. We are at a point now where we need to go in this direction versus what we were doing.”

Recently approved changes to a decades-old program that has helped fuel redevelopment in Richmond through partial real estate tax abatements have some developers and builders who do business in the city on edge.

Richmond City Council last month adopted an ordinance repealing the partial tax exemption for rehabilitated structures, replacing it with a new program that would apply the abatements only to projects that include income-based housing units, with the goal of incentivizing income-based, or “affordable,” housing.

The change, which would take effect July 1, was approved at council’s Jan. 27 meeting as part of its consent agenda, in which business considered routine or non-controversial is lumped together and voted on at once. Council members Ellen Robertson, Michael Jones and President Cynthia Newbille were patrons on the bill.

Under the new program, abatements would be awarded only to multifamily and single-family residential rehabs with at least 30 percent of units set aside for residents making 80 percent or less of the area median income – currently $83,200 in Richmond’s metropolitan statistical area.

Commercial and industrial structures no longer would be eligible, and commercial space in residential mixed-use projects would not be counted in an abatement.

Qualifying structures must be 20 years old and “substantially rehabilitated” within two years of a building permit being issued or application received. Abatements would last up to 15 years and be equal to the increase in assessed property value resulting from the rehab. Traditionally, properties have been required to increase in value at least 40 percent to qualify for the program.

The changes follow recommendations from a 2019 study that the city commissioned from VCU’s Center for Urban and Regional Analysis. They also fall in line with a push to encourage more income-based housing in the city, a la Mayor Levar Stoney’s goal of creating 1,500 affordable housing units by 2023 and initiatives to transition residents from public housing to mixed-income housing.

Study advised changes

The CURA study, which cost the city about $52,000, was requested by city assessor Richie McKeithen, who came on in 2017 after stints in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. McKeithen, who previously worked for Richmond as a deputy assessor in the early 2000s, said he suggested taking a look at the program after council members asked what he thought the department could be doing better.

Noting the program dated back to the 1990s, McKeithen said it had remained largely unchanged despite economic shifts, save for a revision in 2007 that shortened the abatement period from 15 to 10 years, and to seven years for commercial properties outside the city’s enterprise zones. The program also was reviewed in 2013 to address a loophole of sorts regarding additions to structures.

With the study, which CURA conducted in 2018 and submitted in February 2019, McKeithen said: “One of their recommendations was (that) the city is running to a point where you don’t need to continue to give out the program the way you’re doing it now, but you’re having an affordable housing problem, so why don’t you give the program and the incentive to projects that relate to affordable housing.

“Several of the council people had already had a suggestion like that or had thought along those lines,” McKeithen said.

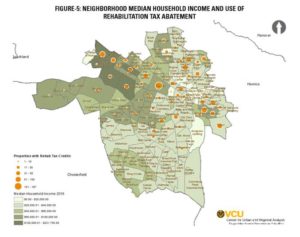

Douglas Dunlap, the city’s housing and community development director, whose department also is involved in the changes, noted the study found that the roughly 1,900 properties that participated in the program between 2009 and 2016 were concentrated in the city’s higher-income areas or stronger housing submarkets. While the program had been used across the city, the study found, poorer neighborhoods with weaker markets had been using it less.

The study also found that the amount of real estate tax revenue foregone due to the abatements during roughly the same period, from 2010 to 2017, totaled over $32 million that otherwise would have added to the city’s coffers.

“It really just substantiated the fact that the individuals who have benefited from the program over the last 10 years or more have primarily been individuals who would have done those projects regardless of whether they were receiving the benefit or not,” Dunlap said.

“The program was used initially to spur development in areas across the city, especially in those areas where we had experienced a period of disinvestment,” he said. “That CURA report really takes into account where we are right now, who’s actually benefiting from the program, (and) confirms that it’s being used on projects in neighborhoods that essentially would be able to afford and would move forward regardless of whether the tax benefit was available or not.

“We are now looking at that as an essential tool, along with other subsidies, to incentivize and continue to expand the supply of affordable units across the city. That’s where we have the greatest need, so that’s where the program will be focused,” Dunlap said.

The amount of tax revenue foregone, and the locations of abatement projects, were points that council member Jones emphasized this week during deliberations about the Navy Hill redevelopment plan that council ultimately voted down. The study found that most abatement projects are single-family rehabs, though the largest share in abatement value had been going to multifamily projects.

City Council member Michael Jones at Monday’s meeting. Jones referenced the abatement program during discussions on the Navy Hill project. (Jonathan Spiers)

“The one thing I’ve heard over is that tax dollars ought not go to private development, but no one is yelling about the tax abatement program,” Jones said at Monday’s council meeting, contending that it has primarily supported individual homes in city districts, including the West End, Northside, Scott’s Addition and Church Hill.

“Individuals want to know why we can’t fund schools; it’s because we have built communities, and not just for communities that are diverse, but for affluent individuals who can afford to pay property taxes,” Jones said.

“For over two and a half years I’ve asked for this study to be done, to look at how we have funded affluent Richmond,” he said. “… You want to build schools? We’re building three. You want to do building maintenance? We don’t have the money to do it, because we’ve built up Scott’s Addition, we’ve built up the Fan, we’ve built up Church Hill to where my grandmother can’t even move back into a house she owned.”

Developers concerned

While the ordinance, which council had continued for over a year, was approved in January with no discussion, it has generated response from Richmond’s development community. Some say the approval went unnoticed and the pending changes are unknown to many who do business and invest in Richmond.

At a council committee meeting last month where the changes were recommended, local developer David Cooley voiced support for keeping the current program going. He was the sole speaker in a public hearing on the ordinance.

“The program is one that has encouraged the restoration, the saving of old houses,” said Cooley, co-founder of Restoration Builders of Virginia.

“I’m fine with tacking the low-income concept onto this incentive program; I’m just standing up in favor of the real estate abatement program that’s currently in place for saving old houses,” he said. “I think it incentivizes us as developers, one more incentive which is needed, to take an old structure and give it new life.”

Danna Markland, CEO of the Home Building Association of Richmond, said she is concerned that a large segment of businesses active in the city has no idea the changes were approved and are coming.

She said the ordinance advanced despite requests from the group’s Multifamily Housing Council and city administrators for more time to negotiate program specifics. She said McKeithen proposed the changes to be relieved of the burden of administering the program, and that many in the homebuilding industry found several of the study’s recommendations problematic.

A map showing the study’s market value analysis of Richmond neighborhoods in relation to program use. (Courtesy VCU CURA)

“Measure the proven track record of the tax abatement against Richmond’s population growth and renaissance since the 1990s. It was the best economic development tool to drive investment citywide,” Markland said in an email.

“Rehabilitation projects are inherently cost-prohibitive. The substantial changes to the partial real estate tax abatement has developers questioning their ability to see current projects through to completion,” she said. “This regressive revocation of its single-family, multifamily and commercial tools will leave a large part of remaining inventory on the table while developers look for other communities where there is land available without structural barriers.”

Brian White, of local development firm Historic Housing and Main Street Realty, likewise said that the changes would result in developers and builders – as well as homeowners – moving away from the city in favor of the counties.

“We have a far higher tax rate than any of the surrounding (localities), and that’s understandable; the city’s got different needs, different realities than what the counties are dealing with,” he said. “But in order to encourage people to invest and pay those, we’re going to need to be creative in attracting some opportunities.

“I just think it’s critically important that we keep the real estate tax abatement in place. It’s been an undeniably powerful driver in rebuilding investment in the city that was fleeing, as if the place was on fire, for a long time,” White said. “I really think this should be a program that gets kept, while you can supplement it with efforts to spur affordable housing. I think that would be a good idea. But to get rid of this is not in the city’s best interest.”

White said Historic Housing, founded by his father David White and Louis Salomonsky, uses the program on about 80 percent of its projects, which are largely historic rehabs for multifamily housing. He said notable rehabs from other developers, such as Ron Stalling’s revival of The Hippodrome Theater and Ted Ukrop’s Quirk Hotel, likely would not have been possible without the program.

“These are real assets to the city and the community,” White said. “If people are not going to reinvest in these buildings, it just seems like a mistake to me.”

White said the investment that resulted from the incentive has contributed greatly to the city’s tax base, the assessed value of which he said has more than doubled over the past 20 years.

“Almost all of the properties that have used this program to help make it possible to reinvest in the city are fully taxable now. The abatements have expired,” he said. “They’re getting a whole lot more money from real estate taxes because of this program.”

White said he’s hopeful that the changes can be tweaked to preserve the current incentive before they take effect in July. He said he plans to reach out to as many council members as he can in the meantime.

“I don’t know what to expect,” he said. “I hope I can demonstrate to them how valuable it has been and continues to be for the city of Richmond.”

Dunlap said the city hasn’t received pushback to the changes as of yet. McKeithen said he’s aware of some concerns with the program but that he hasn’t heard from anyone directly.

“I heard there was some disgruntlement, but how can you argue with the study?” McKeithen said. “That’s why I wanted a study done, by a reputable group, so the facts are the facts. We are at a point now where we need to go in this direction versus what we were doing.”

It’ll be interesting to see how much the rehabilitation / renovation of homes in Richmond slows as a result of this change. I understand the premise, but like most governmental issues that get spearheaded through, they are found to come up short in the real world application. I don’t believe the intended result will be as positive as hoped for. If you have not read Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand, I encourage you to do so. Speaking of taxes: I for one would appreciate knowing exactly, to the penny, where the money collected as a result of the Stormwater Tax… Read more »

Yeah I’ll be at the assessors office today with some questions. What about all the money that was put into the City coffers through redevelopment participation in the program? Billions? Ridiculous this was intentionally hid from the public.

Leave it to City Council to eviscerate an abatement program which has been the driving force behind the rehab boom in Richmond. The same Council that believes a new school building will improve education. “Hey, Cynthia Newbille – If you really care about the east end and its poorer residents, how about ridding us (and them) of the failed progressive experiment known as the housing projects.”

Math is hard, apparently. Also: How will the city pay the additional cost of ‘monitoring’ whether properties in the “NEW!” rehab tax credit program are being rented or sold to people that meet the income requirements?

Do you have a link to the study? Thanks for your article.

I suspect this change will have little impact on the renovation of single family properties. My concern is the potential impact on commercial property development. Will this slow development in Scott’s addition? If there is no incentive to rehab buildings will the be torn down?

Why couldn’t it be an, and approach? Perhaps modify the existing program for commercial projects AND create a program specifically for income-based housing AND earmark a percentage of tax revenues from the new commercial projects to support low-income housing?

This new ordinance is geared to huge developments and huge development companies. How is this going to impact Brookland Park Boulevard and all the commercial structures there? Church Hill or the Nine Mile Road Corridor? Or any other historic commercial corridor in Richmond? And doesn’t the city want commercial developments in multifamily buildings? Where are people supposed to work in the neighborhoods? This “study” was done by people who have no experience in development or have any idea about Richmond. Take the boiler plate and apply it is pretty much the formula for their “equation.”

This is misguided. The abatement program has been instrumental in job creation and fostering small business activity . This will have a negative impact on individual homeowners, small scale developers and small businesses. It’s not just about large scale multifamily developments. Restaurants and retail shops are on Triple Net leases and tax abatements help lower the barrier and cost of entry for those small businesses. Individual homeowners and small-scale historic renovators have used these programs to save hundreds pf historic properties that needed preservation. It is very misguided and shameful of some City Council members to say areas like Scott’s… Read more »

This is a huge mistake for the City. If you care about historic properties this will highly disincentivized the preservation of old structures. If you care about reducing sprawl and preserving green space this change will disincentivize the recycling of old homes and land in favor of building new neighborhoods. This article did not directly touch on conservation zones, many of which are in blighted areas. But as recently as 2020 I have been involved in renovations and construction on blocks in the City that had zero renovated properties. Policies like tax abatement gave me the comfort that others would… Read more »

Exactly! When a $250,000 home gets flipped with this program and the new homeowner saves $150/mo on their taxes, isn’t this an easy way of making housing more affordable?

Only temporarily and likely at the expense of kicking out the poorer resident that would not be able to afford a $250k home. Granted, we need to find a way to balance both renovating neglected areas of the city without displacing our existing residents.

I’m always dumbfounded when politicians tell you they will add thousands of dollars to your tax bill and it won’t effect people’s behavior! We chose to sell our house when the abatement expired and our taxes climbed to over $5000 a year. And we didn’t buy another house in the city.

Without the abatement, renovators have less incentive for the permit and inspection process. Another unintended consequence of a poorly thought-out policy change.

Fascinating to read how people are opposed to this, and the reasons why. For example – the comment that government intervention is stifling growth. Um, they could have just never had an abatement policy to begin with. The fact that they meddled with taxes to benefit those with access to capital hasn’t been mentioned at all.

Support organic slow growth – not projects and policies that support only those with access to capital.

“Support organic slow growth”

Also known as “dying.”

Not at all Justin. I’m very capable of articulating exactly what I mean, I don’t need you to insert your false narratives in an attempt to mask exactly what I am saying.

If you want fast growth, there are plenty of cities that offer it, feel free to check them out. While you checl them out, talk to the people that live there.

Not all of us who live in Richmond want it to become Denver. Slow organic growth is not synonymous with dying. Please use some rational common sense.

Our limitations (Norfolk as well) prevent us from ever becoming like the cities that have far out paced us. We need to be concerned with getting Richmond back to where it was at its peak while retaining its character and historic fabric. We have been on track with that with restaurants and housing, but still lagging in crucial businesses. This is a city, not some rural town. Growth is what keeps the city healthy and a healthy core makes for a healthy metro.

Will the City add staff to process vacant and blighted properties alongside this change? There’s a substantial amount of property that the City hasn’t done its duty in enforcing, which would have a measurable effect on the tax base if they became inhabited. The tax abatement was successful in saving historic homes that had been neglected for decades and were on the verge of ruin. The companies interested in this type of work are all very committed to the City of Richmond and our neighborhoods and our shared history. The properties may not have all gone to affordable housing but… Read more »

If a key driver of revamping the program is to lessen the administrative burden of the assessor office then injecting an affordable income component only complicates the program and drives up short-term and long-term administration cost to the city, whether it’s falls to the assessment or zoning/planning office (don’t forgot outsourcing zoning inspections was recently proposed). The RE tax burden to the SFR homeowner who meets the 80% of median income of $83K criteria is 14.6% of his/her monthly payment (i.e., P&I, taxes, and insurance). The RE burden rises to > 24% for a SFR homebuyer who is at 50%… Read more »

I commend the council for its step toward responsible management to update ‘rehab’ tax abatement program. Unfortunately, their actions undermine their good intentions. Their lack of openness and failure to gather stakeholders’ input as well as the political tactic to tie the issues of affordable housing and poor schools to the abatement program undermines the trust of the people. The erosion of trust is furthered by statements of key city employees, that one must assume the council relies upon for advice. My review of the CURA report belies some of the talking points of the city. Is the existing abatement… Read more »

I look at Navy Hill and the Tax Abatement programs very differently. Navy Hill was a wild home run swing no one asked for that carried huge risks to the general fund for the next two generations. I’m convinced Richmond would have struck out. No thank you to Navy Hill. The tax abatement program has allowed properties to be slowly redeveloped over time (hit a bunch of singles), when combined, uplifted assessments, tax revenues, and activity in several neighborhoods. Please continue. Time and time again, this city wields a club when it should be holding a scalpel, and vice versa.… Read more »

Hey Jeff. You raise good points., expanded points. Obviously, I think Navy Hill could have been a standout program if council had more it forward in negotiation. You and I agree the city uses a club too often. Thank you for contributing meaningfully to the conversation.