Editor’s note: This is the second in a five-part commentary series from Edwin Slipek on historic preservation issues in various Richmond neighborhoods. Here’s part 1.

As colleges and universities hustle to recalibrate academic offerings and market their respective allures despite post-pandemic uncertainty, some have even ramped up promoting their campuses on-campus.

Beneath the towering pine trees at the University of Richmond, you can’t walk 10 yards without being confronted by a smart-looking, way-finding sign with red and blue topography and an iconic Spider. Despite the school’s relentless gothic revival architecture, the administration must assume those strolling on campus need reminders of where they are.

Virginia Commonwealth University recently installed three large, bold, free-standing letters “VCU” at the busy southeast intersection of West Cary and Harrison streets. Farther up Harrison at Broad Street, a tall clock tower at the Siegel Center contains an electronic, flashing sign that hawks upcoming sports events. And just a few blocks northeast, at Lombardy Street and Brook Road, Virginia Union University has an electronic sign that is largely hidden since it sits on the ground and is mostly blocked from view by a metal fence.

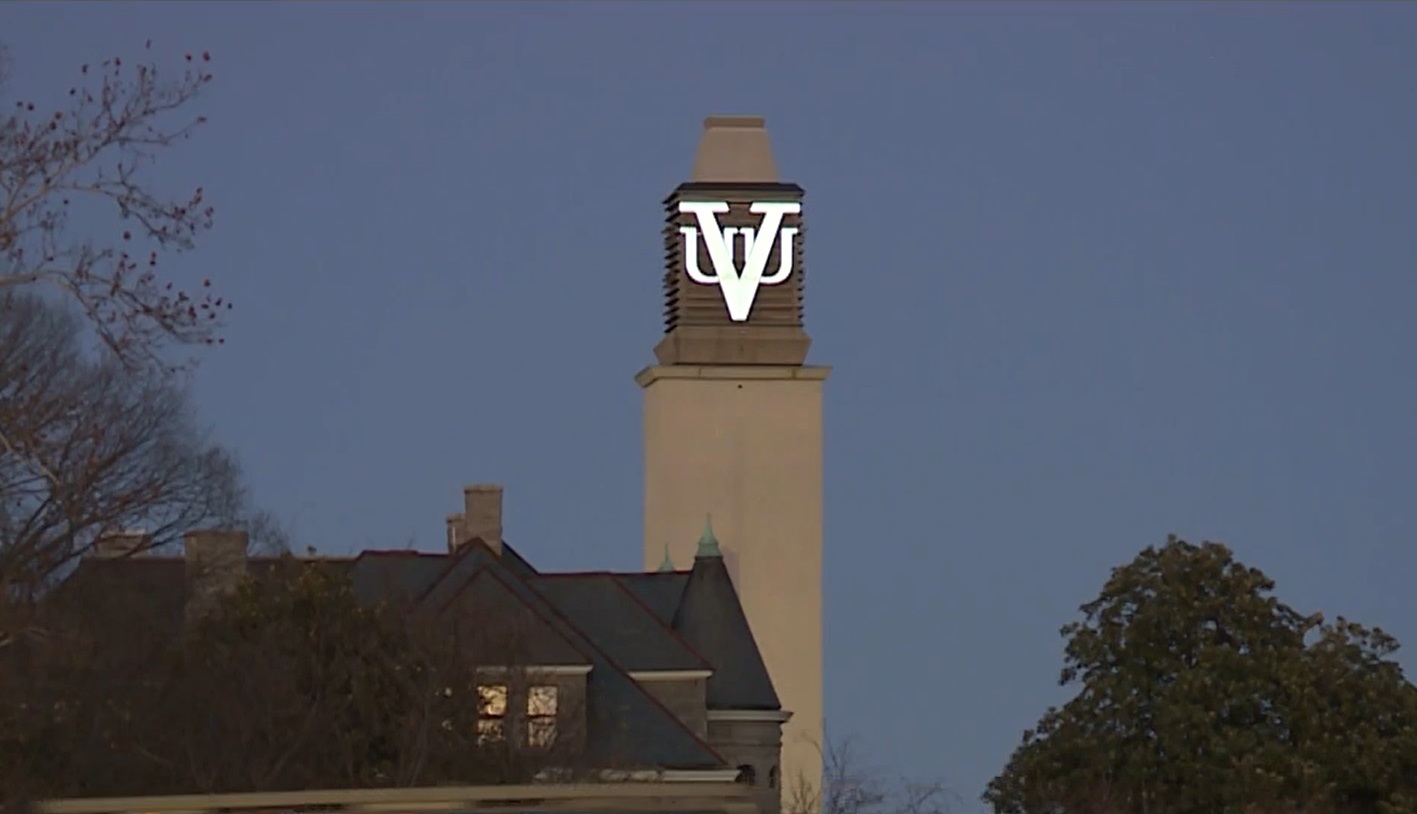

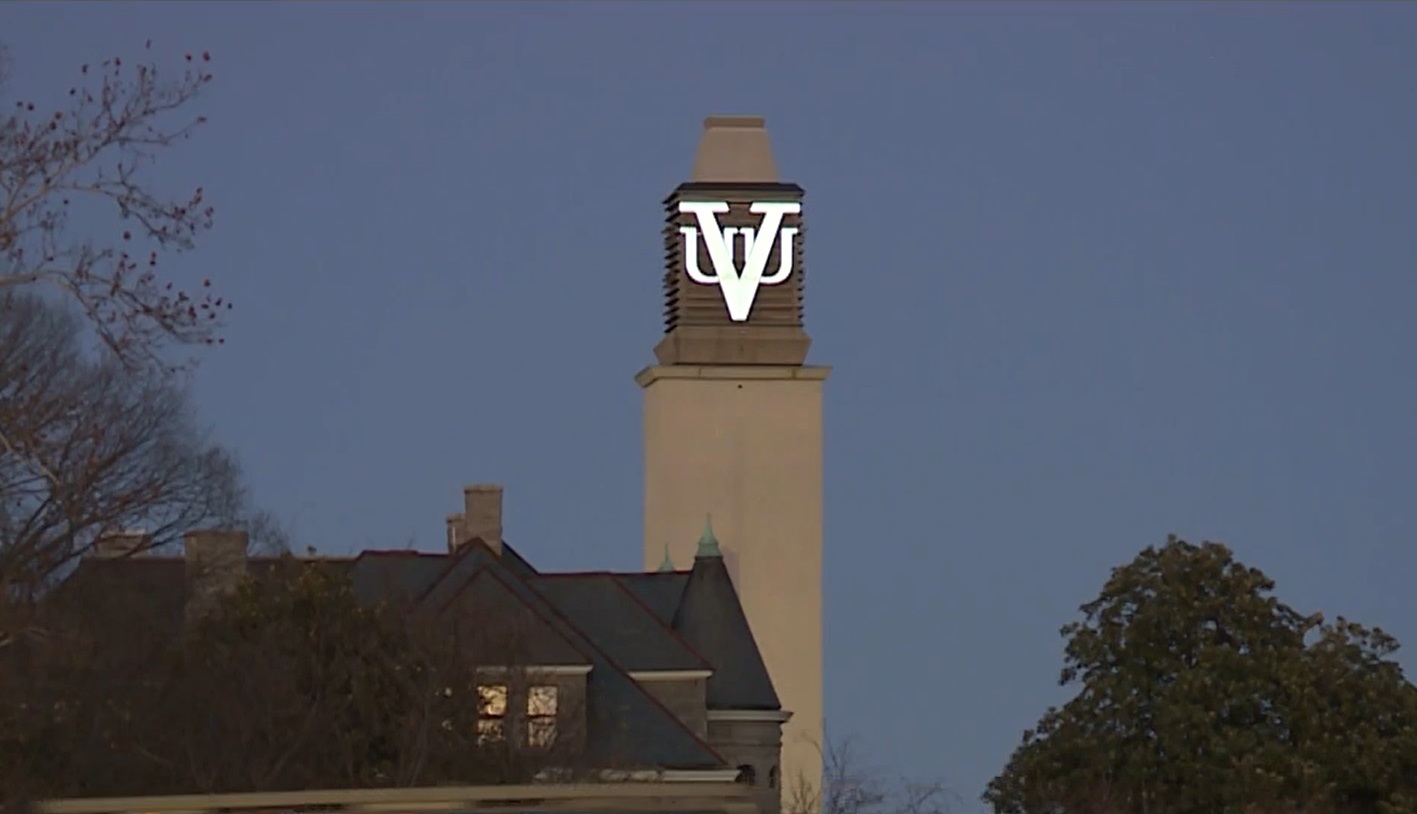

But not to worry. Virginia Union’s top-heavy initials, VUU, are affixed, 150 feet up, to the Belgian Friendship Tower. This national and state historic landmark, with an intriguing international story, was previously the Belgium Pavilion (designed by modernist Belgium architect Henry Van de Velde) at the 1939 New York World’s Fair before it was given to VUU and shipped to Richmond in 1941. “It’s a beacon of hope,” a school official said recently of the inadvertent, and controversial “billboard.”

An illuminated logo sign on Virginia Union University’s Belgian tower. (Screenshot courtesy of WTVR)

But wait. VUU has another signifier that catches many more impressions from passersby each day. This is Industrial Hall, a ruinous landmark from 1899, that can be seen by some 140,000 vehicles daily that pass along the southwest edge of the campus along Interstates 95 and 64. The structure’s preservation and adaptive reuse is one of the most important and challenging reclamation projects facing Northside Richmond. The building is one of eight original and handsome buildings erected when the campus was established here at the end of the 19th century. And sadly, the only one that had apparently been left — through benign neglect — to decay.

First, some history. Virginia Union is an independent, Baptist-affiliated liberal arts institution which had extremely humble beginnings. In 1865, it was established as a school for freed blacks in the former Lumpkin’s Jail in Shockoe Slip. As it grew, it operated out of a former downtown Richmond hotel. In the mid-1890s a number of clergy, educators and philanthropists from northern states purchased and donated acreage for a suburban campus near the Carver neighborhood along the banks of Bacon’s Quarter Branch (the creek now flows underground through culverts along the path of the interstates). With the move to Northside, Virginia Union received its name from the merger of Virginia Theological Seminary and Wayland Seminary. Hartshorn women’s college would join the “Union” in the 1930s.

The planner and architect for the nascent campus was John H. Coxhead, a New Jersey-born, Buffalo, N.Y.-, New York City-, and Washington, D.C.-based designer (1863-1943). He had distinguished himself as an architect for United States Army projects and at least one Baptist church in Buffalo. The eight structures he designed at Union include Industrial Hall, an academic building, a dormitory, chapel and the president’s house. He used gray-hued granite blocks, not unlike those found at Richmond’s old City Hall (1888) to form structures in the style of the prominent and highly influential Boston architect Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1888).

Industrial Hall, constructed near Bacon’s Quarter Branch, housed building design and technical skills programs. Architecturally speaking, Richmond today is predominantly a post-Civil War, late 19th and early 20th century town and many of the students who matriculated here went on to build our city. Chief among the professors who taught and inspired here was Richmond-born and Hampton University-trained Charles T. Russell (1875-1952), historically our city’s most accomplished and important black architect (he supervised his students in assembling the Belgian Friendship Tower).

During the 120 years since the Union campus was established, other buildings in various architectural styles have been added. But the great gray and granite buildings define the place and set a high standard for excellence.

Happily, after years of indifference, Industrial Hall is receiving desperately needed attention. The goal is to transform the structure into an arts center and gallery. With the architecture firm of Quinn Evans and contractor Taylor and Parrish, the university has begun clearing out the interior and stabilizing the four outer walls of the 9,700-square-foot, two-and-a-half-story building.

Funding for the initially budgeted $4.5 million project is coming in (although that figure is now probably low after post-COVID economic adjustments). Major grants include those from the Commonwealth of Virginia Industrial Fund and the Mary Morton Parsons Foundation. Project completion is set for September 2023.

Visual and fine arts programs, including the campus art gallery and art collections, currently housed in the L. Douglas Wilder Library, will be moved here. A highlight of the university’s impressive holdings are artworks by the late Thornton Dial, Sr. a self-taught, highly celebrated artist. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has presented a retrospective of his work in recent years. The Virginia Museum of Art and Harvard University each possess two pieces. Virginia Union has 140 Dials. There are also some 1,000 works by other artists and designers in the university collection.

“What we have been focusing on is STEM, a curriculum of science, technology, engineering and mathematics,” a VUU official said some years ago. “This facility will allow us to emphasize the arts to a greater extent — STEAM for our students.”

Here’s to turning up the heat and full steam ahead.

Editor’s note: This is the second in a five-part commentary series from Edwin Slipek on historic preservation issues in various Richmond neighborhoods. Here’s part 1.

As colleges and universities hustle to recalibrate academic offerings and market their respective allures despite post-pandemic uncertainty, some have even ramped up promoting their campuses on-campus.

Beneath the towering pine trees at the University of Richmond, you can’t walk 10 yards without being confronted by a smart-looking, way-finding sign with red and blue topography and an iconic Spider. Despite the school’s relentless gothic revival architecture, the administration must assume those strolling on campus need reminders of where they are.

Virginia Commonwealth University recently installed three large, bold, free-standing letters “VCU” at the busy southeast intersection of West Cary and Harrison streets. Farther up Harrison at Broad Street, a tall clock tower at the Siegel Center contains an electronic, flashing sign that hawks upcoming sports events. And just a few blocks northeast, at Lombardy Street and Brook Road, Virginia Union University has an electronic sign that is largely hidden since it sits on the ground and is mostly blocked from view by a metal fence.

But not to worry. Virginia Union’s top-heavy initials, VUU, are affixed, 150 feet up, to the Belgian Friendship Tower. This national and state historic landmark, with an intriguing international story, was previously the Belgium Pavilion (designed by modernist Belgium architect Henry Van de Velde) at the 1939 New York World’s Fair before it was given to VUU and shipped to Richmond in 1941. “It’s a beacon of hope,” a school official said recently of the inadvertent, and controversial “billboard.”

An illuminated logo sign on Virginia Union University’s Belgian tower. (Screenshot courtesy of WTVR)

But wait. VUU has another signifier that catches many more impressions from passersby each day. This is Industrial Hall, a ruinous landmark from 1899, that can be seen by some 140,000 vehicles daily that pass along the southwest edge of the campus along Interstates 95 and 64. The structure’s preservation and adaptive reuse is one of the most important and challenging reclamation projects facing Northside Richmond. The building is one of eight original and handsome buildings erected when the campus was established here at the end of the 19th century. And sadly, the only one that had apparently been left — through benign neglect — to decay.

First, some history. Virginia Union is an independent, Baptist-affiliated liberal arts institution which had extremely humble beginnings. In 1865, it was established as a school for freed blacks in the former Lumpkin’s Jail in Shockoe Slip. As it grew, it operated out of a former downtown Richmond hotel. In the mid-1890s a number of clergy, educators and philanthropists from northern states purchased and donated acreage for a suburban campus near the Carver neighborhood along the banks of Bacon’s Quarter Branch (the creek now flows underground through culverts along the path of the interstates). With the move to Northside, Virginia Union received its name from the merger of Virginia Theological Seminary and Wayland Seminary. Hartshorn women’s college would join the “Union” in the 1930s.

The planner and architect for the nascent campus was John H. Coxhead, a New Jersey-born, Buffalo, N.Y.-, New York City-, and Washington, D.C.-based designer (1863-1943). He had distinguished himself as an architect for United States Army projects and at least one Baptist church in Buffalo. The eight structures he designed at Union include Industrial Hall, an academic building, a dormitory, chapel and the president’s house. He used gray-hued granite blocks, not unlike those found at Richmond’s old City Hall (1888) to form structures in the style of the prominent and highly influential Boston architect Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1888).

Industrial Hall, constructed near Bacon’s Quarter Branch, housed building design and technical skills programs. Architecturally speaking, Richmond today is predominantly a post-Civil War, late 19th and early 20th century town and many of the students who matriculated here went on to build our city. Chief among the professors who taught and inspired here was Richmond-born and Hampton University-trained Charles T. Russell (1875-1952), historically our city’s most accomplished and important black architect (he supervised his students in assembling the Belgian Friendship Tower).

During the 120 years since the Union campus was established, other buildings in various architectural styles have been added. But the great gray and granite buildings define the place and set a high standard for excellence.

Happily, after years of indifference, Industrial Hall is receiving desperately needed attention. The goal is to transform the structure into an arts center and gallery. With the architecture firm of Quinn Evans and contractor Taylor and Parrish, the university has begun clearing out the interior and stabilizing the four outer walls of the 9,700-square-foot, two-and-a-half-story building.

Funding for the initially budgeted $4.5 million project is coming in (although that figure is now probably low after post-COVID economic adjustments). Major grants include those from the Commonwealth of Virginia Industrial Fund and the Mary Morton Parsons Foundation. Project completion is set for September 2023.

Visual and fine arts programs, including the campus art gallery and art collections, currently housed in the L. Douglas Wilder Library, will be moved here. A highlight of the university’s impressive holdings are artworks by the late Thornton Dial, Sr. a self-taught, highly celebrated artist. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has presented a retrospective of his work in recent years. The Virginia Museum of Art and Harvard University each possess two pieces. Virginia Union has 140 Dials. There are also some 1,000 works by other artists and designers in the university collection.

“What we have been focusing on is STEM, a curriculum of science, technology, engineering and mathematics,” a VUU official said some years ago. “This facility will allow us to emphasize the arts to a greater extent — STEAM for our students.”

Here’s to turning up the heat and full steam ahead.

As usual, Ed Slipek has written an excellent piece. There is a tiny mistake, the founding date of the theology school that became Virginia Union. The American Baptist Association did authorize the school in 1865, but the first minister could not find any space and left to run a school he founded in Burma. His replacement also could not find a place until 1867 when the widow of slave jail owner Robert Lumpkin agreed to rent the former jail for use by the school. The events and Mary Lumkin’s role are detailed in the new biography of Mrs. Lumpkin, “The… Read more »

Another excellent piece, Ed! Keep up the great writing!

Ed Slipek for Richmond mayor in 2024!