The former Manchester Post Office dates back to 1908 and was renovated in the late 2000s. (Mike Platania photo)

In 2008, veteran local real estate developer Charles Macfarlane struck a deal with the City of Richmond to buy the former Manchester Post Office at 1019 Hull St.

The agreement called for Macfarlane to convert the decommissioned postal building into office space. The deal also included covenants that Macfarlane wouldn’t raze the century-old building.

All went as planned. Macfarlane paid the city $200,000 for the property and the building has since been transformed into office space, with transportation software company Iteris its latest tenant.

But in recent years Macfarlane has grown increasingly frustrated when his real estate tax bills arrive and he sees that the city has assessed the old post office, along with his other historic-preservation properties, at rates that, he says, don’t take into account the special deed restrictions they’re subject to.

Last year the city assessed the Hull Street property’s 0.4-acre plot at $701,000, or $39.63 per square foot. That equates to a tax bill of $14,400.

Macfarlane is particularly frustrated that the city appears to be valuing the land upon which the building sits in line with neighboring properties that are ripe for sizable redevelopments in a neighborhood that’s become a development hotbed.

For example, half a mile away is the 3-acre riverfront site at 301 W. Sixth St. where New York developer Avery Hall Investments is planning a pair of apartment towers that would reach 16 and 17 stories. That property was assessed this year at $40.98 per square foot, just $1 per square foot more than Macfarlane’s post office parcel.

Macfarlane said by using developable lots as comparisons for assessing the value of historic-preservation properties, those historic properties’ values get wrongly inflated.

“The city puts (historic properties) in a different class or category, and that should, in my opinion, allow the assessor to say, ‘Yes, that property is different, it has existing long-term agreements or deed restrictions that restrict its use,’” he said. “It’s hard for us to justify paying $40 per square foot for real estate taxes on an annual basis.”

City records show that in 2020 the post office building was valued at $722,000 and its land was valued at $425,000. But the value of the land and buildings has effectively flipped in recent years. In its latest assessment, the building was valued at $499,000 and the land was at $701,000.

Macfarlane said the rising assessments make owning the historic properties a burden and incentivize him to sell. If he sold something like the Hull Street post office, the buyer wouldn’t be obligated to preserve it the way he has, since they would not be subject to the same agreement Macfarlane made with the city.

“They’d be able to tear it down and build something up to five or six stories,” he said. “And it would be unfortunate because I don’t think that’s what the neighborhood or the community would want.”

Macfarlane’s situation is one example of what in recent years has been an up-and-down trend of Richmond property owners questioning and formally appealing the city’s real estate tax assessments, particularly in certain sought-after neighborhoods.

An inexact science

Each year Richmond assesses the value of the roughly 76,000 individual parcels within the city limits and taxes them at a rate of $1.20 per $100 of assessed value.

A BizSense analysis of city assessment data found that the value of the roughly 10,000 commercial and multifamily properties in the city has in general, unsurprisingly, gone up in recent years. Since 2020, the cumulative assessed value of all the commercial properties in Richmond has risen 26 percent.

In Manchester over that same period, assessments have gone up about 29 percent. In Scott’s Addition, another neighborhood that’s drawn considerable developer interest, commercial assessments have gone up 69 percent over the last four years.

While a residential property’s assessment value is based only on comparable sales and how much it would cost to replace the structure on the parcel, commercial assessments also take into account how much operating income the property generates.

The assessed value of all the commercial property in Scott’s Addition has gone up 69 percent since 2020. (Photo courtesy SkyShots Photography)

City Assessor Richie McKeithen said his office must assess properties based on those factors up to a specific cutoff date each year, making it difficult to keep up in hot neighborhoods where values change rapidly.

“With a market as strong as Scott’s Addition, commercially, where people are just trying to get in no matter the cost, it’s harder for us to equate that assessed value exactly because, one, we had to cut off maybe nine months ago,” McKeithen said. “And two, that neighborhood is running so strong that people are paying above and beyond market value just to get in.”

Another hurdle, McKeithen said, is that there are no state laws that require commercial property owners to disclose a property’s operating income, often eliminating one of the three factors the city can use to assess its value.

McKeithen said assessors in Virginia are required by law to assess properties based on their “highest and best use as determined by their zoning,” and they can’t take into account whether a property owner wants to develop or sell their land. Assessors simply have to determine a property’s market value at a specific moment in time.

“You can’t value a property based on what the property owner wants to do or not do, because you don’t know when the property owner’s going to change their mind,” McKeithen said. “You have to value it as though it is for sale.”

In order to assess the tens of thousands of parcels each year, the assessor’s office and its staff of 38 uses software from California-based mass appraisal firm CoreLogic called Marshall & Swift, which calculates how much it thinks it would cost to replace a building with one of equal utility.

Marshall & Swift is popular among municipalities throughout the U.S., but since it calculates using only one metric – replacement cost – critics say it shouldn’t be relied upon entirely.

One such critic is Shane Smith, an attorney at Williams Mullen who’s been focusing on real estate assessment disputes for over 15 years. He often represents property owners in Virginia in tax assessment appeals.

Smith said computer-assisted mass appraisal platforms that use construction cost estimation services like Marshall & Swift are attractive to localities because they allow assessors to essentially “punch a button and the computer generates a number.” He said many assessors’ offices don’t often have the budget or staff to also perform income and/or sales comparison approaches.

“The law doesn’t say that you have to use all three appraisal approaches, but you at least are supposed to make an effort to gather the information necessary to determine the applicability of all three approaches,” Smith said.

“One of the main problems that we’ve seen in Virginia for years is that that never happens. From my perspective, there is a widespread default to the sole use of a (replacement) cost approach because it’s easy.”

Another flaw in the system, particularly related to commercial assessments, is that finding comparable sales for commercial land in Richmond is rather difficult.

Developers eager to build in neighborhoods like Scott’s Addition, the Museum District and Manchester have all paid premiums for buildings that they want to knock down, solely to get to the land underneath. Such sales, some of which have been record-setting, make it more difficult to assess the value of the dirt since the deal involved more than just the land.

“That’s a fact of the way things are in Richmond,” Smith said. “There’s no vacant land to buy. If you buy a property for redevelopment, you’re obviously going to have to demolish what’s there first. What that means is there aren’t any sales of vacant land available to the city to clearly and accurately determine what the land values are, in my opinion.”

Assessment appeals can be an uphill battle

Property owners like Macfarlane who feel their assessments are too high can file appeals to the assessor for an office review, which is conducted by a member of the assessor’s staff. For office reviews, property owners must provide data that supports their case and “indicates the subject assessment is inequitable with similar classed properties,” as stated by the assessor’s office.

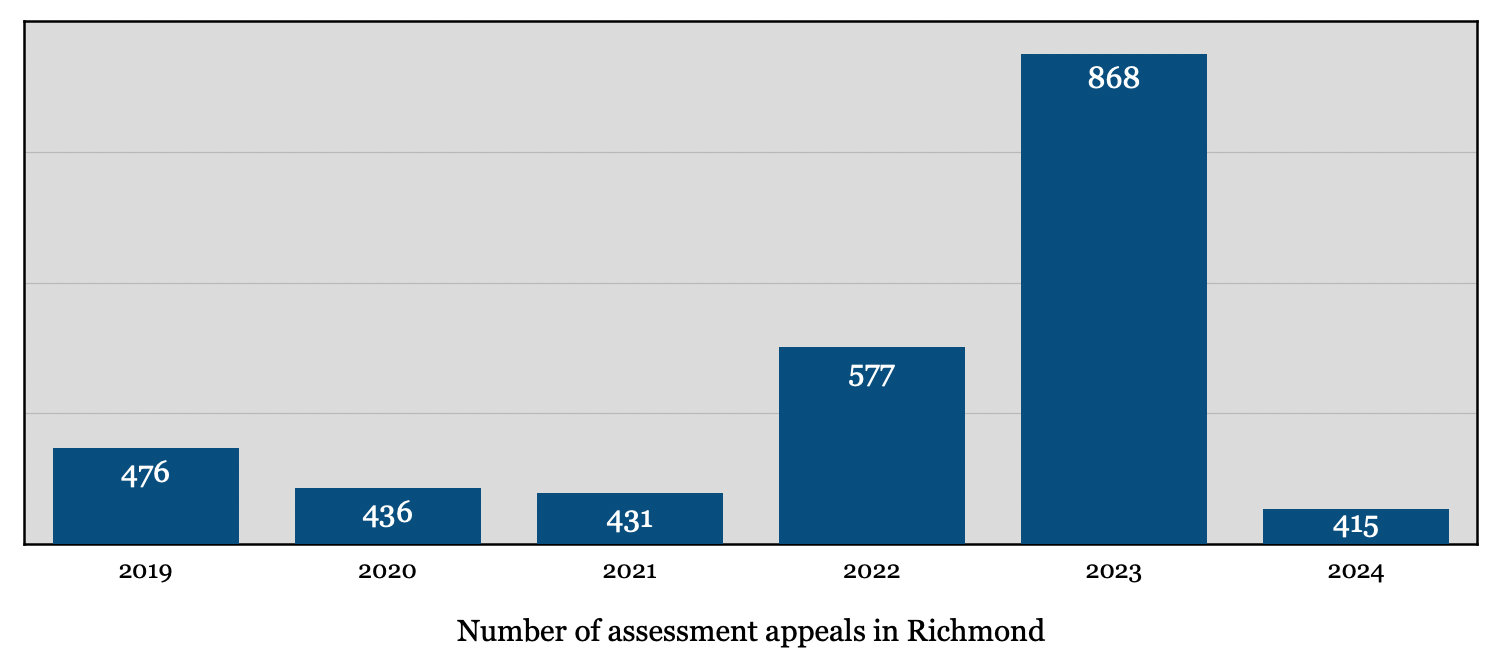

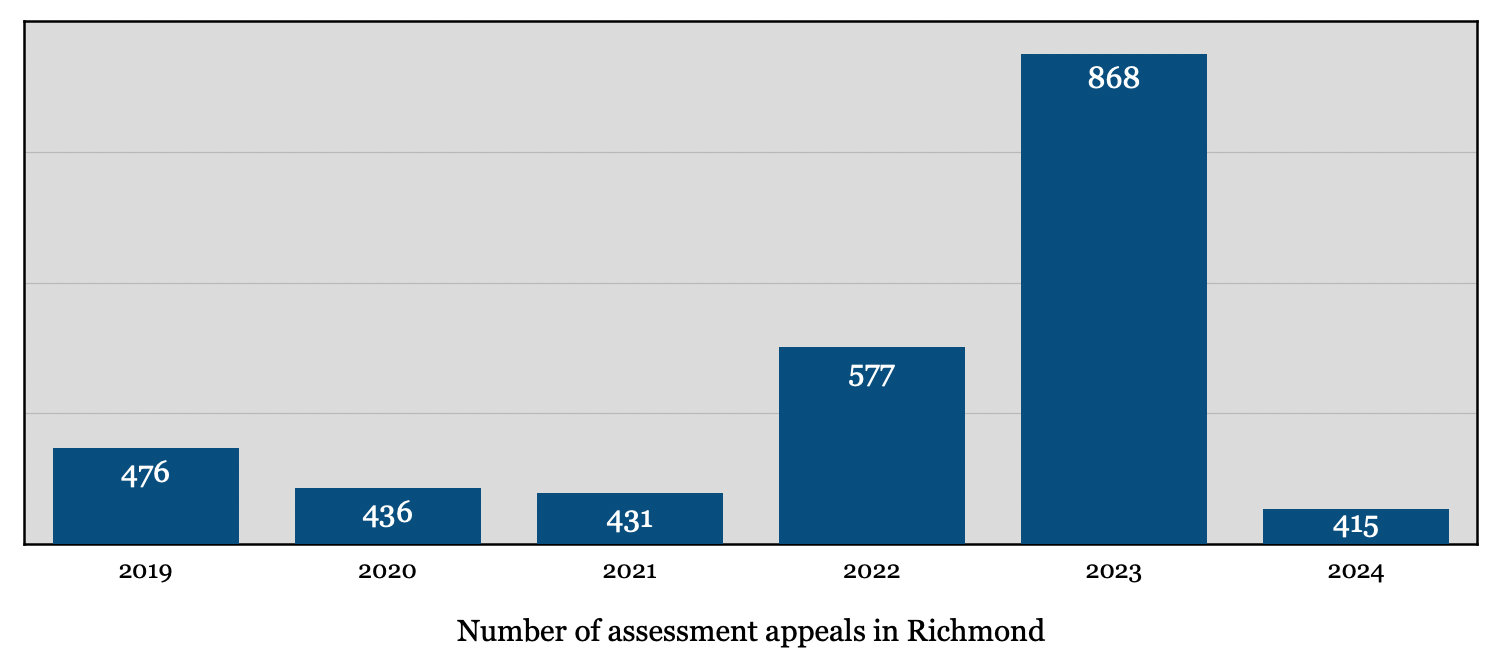

According to data provided by the city, from 2019 to 2021 the assessor’s office heard between 431 and 476 appeals from property owners in Richmond. That number jumped to 577 in 2022 before topping out at 868 in 2023.

That surge in appeals coincided with low interest rates and a highly competitive market for both homebuyers and developers in Richmond, and McKeithen said typically around 60 percent of the appeals in a given year are for single-family residential houses.

In 2024 assessment appeals dropped off significantly, with only 415 filed.

If the appeal is denied at the office review level, property owners can bring their case to the Richmond Board of Equalization.

In Virginia, Boards of Equalization are either three- or five-person bodies that are appointed by Circuit Court judges in each locality to review assessment appeal cases. State law requires that at least 30 percent of the members of a Board of Equalization work in the real estate industry.

Richmond’s Board of Equalization counts three people: local Long & Foster agents Cathy Saunders and Jeff Donahue, and John Nelms, who had been Hanover County’s assessor before retiring in 2012.

Hearings for the Richmond Board of Equalization take place in a conference room in the assessor’s office in City Hall. Most appellants call in by phone, take an oath that they’re telling the truth, and then make their case to the board.

Appellants in recent years haven’t had much luck at both levels of the appeals process.

Roughly 30 percent of all office review appeal cases between 2019 and 2023 were successful. Appellants that were unsuccessful at the office review level and brought their case before the Board of Equalization were marginally less successful in that period, with a win rate of 29 percent.

One recent hearing of Richmond’s Board of Equalization put on display the challenges both the assessor’s office and property owners are facing in the city’s red-hot real estate market, when a homeowner in Bellevue disputed a recent 21 percent increase in his property’s assessed value.

The board asked the homeowner what he thinks his property is worth. The homeowner said that, to him, his property’s worth millions of dollars, because he doesn’t want to move.

The board responded by noting that recent sales show low supply and high demand have been driving up home prices throughout Bellevue.

The homeowner argued that supply and demand shouldn’t matter in his case, because his house isn’t for sale.

The homeowner’s request was ultimately denied.

McKeithen offered an example of why assessors can’t take into account whether a parcel is for sale when they value it.

“It’s like a precious diamond. If you have a precious diamond, the owner might not want to sell it. But it’s still worth $10 million whether they want to sell it or not,” McKeithen said.

Macfarlane also owns the Adam Craig House at 1812 E. Grace St., the assessment of which he’s also appealed in recent years.

Macfarlane, who owns the aforementioned Hull Street post office, as well as the historically protected, 240-year-old Adam Craig House at 1812 E. Grace St. in Shockoe Bottom, is no stranger to the Richmond Board of Equalization.

While he doesn’t appeal the assessments of his new-construction developments like Main2525, Macfarlane has been filing appeals for his historic buildings in recent years, often getting shot down at the office review level before going before the Board of Equalization. He’s appealed the assessment of the Adam Craig House a handful of times in the 26 years he’s owned it, and said he’s appealed the Hull Street post office the last four or five years running.

At his board hearing in February, Macfarlane argued that the Manchester Post Office shouldn’t be compared to properties like Avery Hall’s on West Sixth Street, where a pair of high-rises are set to be built.

During Macfarlane’s hearing, Donahue, the Board of Equalization’s chairman, said that he thinks the old post office building is part of the fabric of the neighborhood, and that it’s a type of building that’s worth saving.

“I think it’s a valuable building,” Donahue said. “It’s definitely the land that’s throwing a monkey wrench into it.”

But he also noted that Macfarlane’s tax credits on the parcel expired. Technically, Macfarlane could try to redevelop the property, Donahue suggested.

“I’m here to tell you I wouldn’t do that,” Macfarlane responded, “based on the representations I made (to the city) when we purchased it, and what our role is in the community.”

A few weeks later he received a notice that the Board of Equalization ultimately decided against lowering the post office’s assessment. Macfarlane said the notice was brief.

“They never provided any justification or any explanation for why they rejected our claim,” he said. “What’s really disconcerting and frustrating to me is that they gave the impression during the hearing that they agreed with the point we were making and they seemed to acknowledge the difference (in the properties).”

‘A position of public trust’

Smith, the lawyer with Williams Mullen, said there’s often a connection between hot markets and the volume of assessment appeals.

“To be fair to the assessor, in a market where values are increasing, you’re going to have people that get upset,” Smith said. “People want to pay the price they want to pay for a house, and then when they get an assessment that’s in line with that price, they change their tune.”

But he said he still sees issues with the appeals processes.

A homeowner may have a credible gripe over their assessment, but to win a case at the Board of Equalization, Smith said it typically requires the help of an attorney like himself or another consultant, prompting many to give up on their case. That seems to be the case in Richmond, as in 2023, 40 percent of all appeal cases that reached the Richmond Board of Equalization wound up getting withdrawn.

“If you’re going to save $300 (on an assessment), how much of somebody’s time can you buy to help you? That’s not even enough to get started,” Smith said.

“Those are the (cases) that are really frustrating to me: people who have legitimate complaints about their assessment and can’t afford to get the help they need to get it corrected.…It’s them against the world and they’re not going to be able to get professional help. To me that doesn’t look right,” Smith added.

Now that the Board of Equalization has ruled against his case, Macfarlane could go one step further and bring his appeal into Richmond Circuit Court, but he said he’s not likely to since it could cost upwards of $25,000 to litigate it. That’s more than the tax bill on his Hull Street property, and roughly the total amount Macfarlane estimates he’s spent pursuing appeals in recent years.

“It’s just not feasible (to bring it into court),” Macfarlane said. “It doesn’t make economic sense.”

Board of Equalization hearings are held in City Hall, and property owners can also bring their cases to Richmond Circuit Court. (SkyShots Photography)

Donahue said in an interview that having an attorney isn’t always necessary for appellants at the Board of Equalization, but noted that having some sort of real estate professional is helpful, especially if they can provide evidence on comparable sales.

“A lot of times we have appellants come in and they say, ‘I don’t like my assessments. It’s too high.’ (Then the board says) ‘Why do you think it’s too high?’ ‘It’s just too high,’” Donahue said. “That’s not an argument. That doesn’t provide us with enough information to consider your case.”

“You have to come in with legitimate facts and figures, data that gives us the opportunity to compare that with what the city assessor’s office has done….(Appellants) need to almost hyper-focus on their location and reach out in the geographic area around them to find the anomalies that may help their case.”

Virginia law requires that localities regularly assess the real estate in their jurisdiction, and it references standards established by the International Association of Assessment Officers, guidelines that McKeithen, the city assessor, said his department follows.

But there’s not much in the code that dictates assessment methodologies; i.e., whether to use cost-based, sales comparison or income approaches. Smith sees that as a problem.

“There is no real estate tax assessment code in Virginia,” he said. “There is a statute that requires localities to assess real estate in accordance with generally accepted appraisal practices, procedures, rules and standards. But there’s not any real statutory framework that defines what that means, and so what happens on a practical basis is you could have 140-some-odd different assessors or commissioners of the revenue in Virginia who do things differently. So there’s a real lack of consistency across the commonwealth.”

Smith said there needs to be a statewide commitment to assessing properties as accurately as possible, but that he doesn’t believe there’s much political willpower to change the code to do that.

“I’ll sum it up to say, in my opinion, there are more areas of deep concern than there are areas of deep relief by an order of several magnitudes,” Smith said of modern assessing in Virginia.

“I respect that it’s difficult sometimes to find the right people or to retain the best help once you have it. But those aren’t legitimate excuses. This is a position of public trust in my mind. You’re taking money out of people’s pockets, you’re the person determining what their property tax bill is. And you have an obligation to do it right. No matter how hard it is.”

Donahue said it’s a tall task for the city to accurately reassess each property every single year, and that even with time-saving tools like mass appraisal software, assessors inevitably trail the market.

“Every property is unique and the assessor’s office does not have the time, manpower or ability to physically look at every property to reassess. It’s impossible,” Donahue said. “But I think that department and the people that are in there do a good job.”

The former Manchester Post Office dates back to 1908 and was renovated in the late 2000s. (Mike Platania photo)

In 2008, veteran local real estate developer Charles Macfarlane struck a deal with the City of Richmond to buy the former Manchester Post Office at 1019 Hull St.

The agreement called for Macfarlane to convert the decommissioned postal building into office space. The deal also included covenants that Macfarlane wouldn’t raze the century-old building.

All went as planned. Macfarlane paid the city $200,000 for the property and the building has since been transformed into office space, with transportation software company Iteris its latest tenant.

But in recent years Macfarlane has grown increasingly frustrated when his real estate tax bills arrive and he sees that the city has assessed the old post office, along with his other historic-preservation properties, at rates that, he says, don’t take into account the special deed restrictions they’re subject to.

Last year the city assessed the Hull Street property’s 0.4-acre plot at $701,000, or $39.63 per square foot. That equates to a tax bill of $14,400.

Macfarlane is particularly frustrated that the city appears to be valuing the land upon which the building sits in line with neighboring properties that are ripe for sizable redevelopments in a neighborhood that’s become a development hotbed.

For example, half a mile away is the 3-acre riverfront site at 301 W. Sixth St. where New York developer Avery Hall Investments is planning a pair of apartment towers that would reach 16 and 17 stories. That property was assessed this year at $40.98 per square foot, just $1 per square foot more than Macfarlane’s post office parcel.

Macfarlane said by using developable lots as comparisons for assessing the value of historic-preservation properties, those historic properties’ values get wrongly inflated.

“The city puts (historic properties) in a different class or category, and that should, in my opinion, allow the assessor to say, ‘Yes, that property is different, it has existing long-term agreements or deed restrictions that restrict its use,’” he said. “It’s hard for us to justify paying $40 per square foot for real estate taxes on an annual basis.”

City records show that in 2020 the post office building was valued at $722,000 and its land was valued at $425,000. But the value of the land and buildings has effectively flipped in recent years. In its latest assessment, the building was valued at $499,000 and the land was at $701,000.

Macfarlane said the rising assessments make owning the historic properties a burden and incentivize him to sell. If he sold something like the Hull Street post office, the buyer wouldn’t be obligated to preserve it the way he has, since they would not be subject to the same agreement Macfarlane made with the city.

“They’d be able to tear it down and build something up to five or six stories,” he said. “And it would be unfortunate because I don’t think that’s what the neighborhood or the community would want.”

Macfarlane’s situation is one example of what in recent years has been an up-and-down trend of Richmond property owners questioning and formally appealing the city’s real estate tax assessments, particularly in certain sought-after neighborhoods.

An inexact science

Each year Richmond assesses the value of the roughly 76,000 individual parcels within the city limits and taxes them at a rate of $1.20 per $100 of assessed value.

A BizSense analysis of city assessment data found that the value of the roughly 10,000 commercial and multifamily properties in the city has in general, unsurprisingly, gone up in recent years. Since 2020, the cumulative assessed value of all the commercial properties in Richmond has risen 26 percent.

In Manchester over that same period, assessments have gone up about 29 percent. In Scott’s Addition, another neighborhood that’s drawn considerable developer interest, commercial assessments have gone up 69 percent over the last four years.

While a residential property’s assessment value is based only on comparable sales and how much it would cost to replace the structure on the parcel, commercial assessments also take into account how much operating income the property generates.

The assessed value of all the commercial property in Scott’s Addition has gone up 69 percent since 2020. (Photo courtesy SkyShots Photography)

City Assessor Richie McKeithen said his office must assess properties based on those factors up to a specific cutoff date each year, making it difficult to keep up in hot neighborhoods where values change rapidly.

“With a market as strong as Scott’s Addition, commercially, where people are just trying to get in no matter the cost, it’s harder for us to equate that assessed value exactly because, one, we had to cut off maybe nine months ago,” McKeithen said. “And two, that neighborhood is running so strong that people are paying above and beyond market value just to get in.”

Another hurdle, McKeithen said, is that there are no state laws that require commercial property owners to disclose a property’s operating income, often eliminating one of the three factors the city can use to assess its value.

McKeithen said assessors in Virginia are required by law to assess properties based on their “highest and best use as determined by their zoning,” and they can’t take into account whether a property owner wants to develop or sell their land. Assessors simply have to determine a property’s market value at a specific moment in time.

“You can’t value a property based on what the property owner wants to do or not do, because you don’t know when the property owner’s going to change their mind,” McKeithen said. “You have to value it as though it is for sale.”

In order to assess the tens of thousands of parcels each year, the assessor’s office and its staff of 38 uses software from California-based mass appraisal firm CoreLogic called Marshall & Swift, which calculates how much it thinks it would cost to replace a building with one of equal utility.

Marshall & Swift is popular among municipalities throughout the U.S., but since it calculates using only one metric – replacement cost – critics say it shouldn’t be relied upon entirely.

One such critic is Shane Smith, an attorney at Williams Mullen who’s been focusing on real estate assessment disputes for over 15 years. He often represents property owners in Virginia in tax assessment appeals.

Smith said computer-assisted mass appraisal platforms that use construction cost estimation services like Marshall & Swift are attractive to localities because they allow assessors to essentially “punch a button and the computer generates a number.” He said many assessors’ offices don’t often have the budget or staff to also perform income and/or sales comparison approaches.

“The law doesn’t say that you have to use all three appraisal approaches, but you at least are supposed to make an effort to gather the information necessary to determine the applicability of all three approaches,” Smith said.

“One of the main problems that we’ve seen in Virginia for years is that that never happens. From my perspective, there is a widespread default to the sole use of a (replacement) cost approach because it’s easy.”

Another flaw in the system, particularly related to commercial assessments, is that finding comparable sales for commercial land in Richmond is rather difficult.

Developers eager to build in neighborhoods like Scott’s Addition, the Museum District and Manchester have all paid premiums for buildings that they want to knock down, solely to get to the land underneath. Such sales, some of which have been record-setting, make it more difficult to assess the value of the dirt since the deal involved more than just the land.

“That’s a fact of the way things are in Richmond,” Smith said. “There’s no vacant land to buy. If you buy a property for redevelopment, you’re obviously going to have to demolish what’s there first. What that means is there aren’t any sales of vacant land available to the city to clearly and accurately determine what the land values are, in my opinion.”

Assessment appeals can be an uphill battle

Property owners like Macfarlane who feel their assessments are too high can file appeals to the assessor for an office review, which is conducted by a member of the assessor’s staff. For office reviews, property owners must provide data that supports their case and “indicates the subject assessment is inequitable with similar classed properties,” as stated by the assessor’s office.

According to data provided by the city, from 2019 to 2021 the assessor’s office heard between 431 and 476 appeals from property owners in Richmond. That number jumped to 577 in 2022 before topping out at 868 in 2023.

That surge in appeals coincided with low interest rates and a highly competitive market for both homebuyers and developers in Richmond, and McKeithen said typically around 60 percent of the appeals in a given year are for single-family residential houses.

In 2024 assessment appeals dropped off significantly, with only 415 filed.

If the appeal is denied at the office review level, property owners can bring their case to the Richmond Board of Equalization.

In Virginia, Boards of Equalization are either three- or five-person bodies that are appointed by Circuit Court judges in each locality to review assessment appeal cases. State law requires that at least 30 percent of the members of a Board of Equalization work in the real estate industry.

Richmond’s Board of Equalization counts three people: local Long & Foster agents Cathy Saunders and Jeff Donahue, and John Nelms, who had been Hanover County’s assessor before retiring in 2012.

Hearings for the Richmond Board of Equalization take place in a conference room in the assessor’s office in City Hall. Most appellants call in by phone, take an oath that they’re telling the truth, and then make their case to the board.

Appellants in recent years haven’t had much luck at both levels of the appeals process.

Roughly 30 percent of all office review appeal cases between 2019 and 2023 were successful. Appellants that were unsuccessful at the office review level and brought their case before the Board of Equalization were marginally less successful in that period, with a win rate of 29 percent.

One recent hearing of Richmond’s Board of Equalization put on display the challenges both the assessor’s office and property owners are facing in the city’s red-hot real estate market, when a homeowner in Bellevue disputed a recent 21 percent increase in his property’s assessed value.

The board asked the homeowner what he thinks his property is worth. The homeowner said that, to him, his property’s worth millions of dollars, because he doesn’t want to move.

The board responded by noting that recent sales show low supply and high demand have been driving up home prices throughout Bellevue.

The homeowner argued that supply and demand shouldn’t matter in his case, because his house isn’t for sale.

The homeowner’s request was ultimately denied.

McKeithen offered an example of why assessors can’t take into account whether a parcel is for sale when they value it.

“It’s like a precious diamond. If you have a precious diamond, the owner might not want to sell it. But it’s still worth $10 million whether they want to sell it or not,” McKeithen said.

Macfarlane also owns the Adam Craig House at 1812 E. Grace St., the assessment of which he’s also appealed in recent years.

Macfarlane, who owns the aforementioned Hull Street post office, as well as the historically protected, 240-year-old Adam Craig House at 1812 E. Grace St. in Shockoe Bottom, is no stranger to the Richmond Board of Equalization.

While he doesn’t appeal the assessments of his new-construction developments like Main2525, Macfarlane has been filing appeals for his historic buildings in recent years, often getting shot down at the office review level before going before the Board of Equalization. He’s appealed the assessment of the Adam Craig House a handful of times in the 26 years he’s owned it, and said he’s appealed the Hull Street post office the last four or five years running.

At his board hearing in February, Macfarlane argued that the Manchester Post Office shouldn’t be compared to properties like Avery Hall’s on West Sixth Street, where a pair of high-rises are set to be built.

During Macfarlane’s hearing, Donahue, the Board of Equalization’s chairman, said that he thinks the old post office building is part of the fabric of the neighborhood, and that it’s a type of building that’s worth saving.

“I think it’s a valuable building,” Donahue said. “It’s definitely the land that’s throwing a monkey wrench into it.”

But he also noted that Macfarlane’s tax credits on the parcel expired. Technically, Macfarlane could try to redevelop the property, Donahue suggested.

“I’m here to tell you I wouldn’t do that,” Macfarlane responded, “based on the representations I made (to the city) when we purchased it, and what our role is in the community.”

A few weeks later he received a notice that the Board of Equalization ultimately decided against lowering the post office’s assessment. Macfarlane said the notice was brief.

“They never provided any justification or any explanation for why they rejected our claim,” he said. “What’s really disconcerting and frustrating to me is that they gave the impression during the hearing that they agreed with the point we were making and they seemed to acknowledge the difference (in the properties).”

‘A position of public trust’

Smith, the lawyer with Williams Mullen, said there’s often a connection between hot markets and the volume of assessment appeals.

“To be fair to the assessor, in a market where values are increasing, you’re going to have people that get upset,” Smith said. “People want to pay the price they want to pay for a house, and then when they get an assessment that’s in line with that price, they change their tune.”

But he said he still sees issues with the appeals processes.

A homeowner may have a credible gripe over their assessment, but to win a case at the Board of Equalization, Smith said it typically requires the help of an attorney like himself or another consultant, prompting many to give up on their case. That seems to be the case in Richmond, as in 2023, 40 percent of all appeal cases that reached the Richmond Board of Equalization wound up getting withdrawn.

“If you’re going to save $300 (on an assessment), how much of somebody’s time can you buy to help you? That’s not even enough to get started,” Smith said.

“Those are the (cases) that are really frustrating to me: people who have legitimate complaints about their assessment and can’t afford to get the help they need to get it corrected.…It’s them against the world and they’re not going to be able to get professional help. To me that doesn’t look right,” Smith added.

Now that the Board of Equalization has ruled against his case, Macfarlane could go one step further and bring his appeal into Richmond Circuit Court, but he said he’s not likely to since it could cost upwards of $25,000 to litigate it. That’s more than the tax bill on his Hull Street property, and roughly the total amount Macfarlane estimates he’s spent pursuing appeals in recent years.

“It’s just not feasible (to bring it into court),” Macfarlane said. “It doesn’t make economic sense.”

Board of Equalization hearings are held in City Hall, and property owners can also bring their cases to Richmond Circuit Court. (SkyShots Photography)

Donahue said in an interview that having an attorney isn’t always necessary for appellants at the Board of Equalization, but noted that having some sort of real estate professional is helpful, especially if they can provide evidence on comparable sales.

“A lot of times we have appellants come in and they say, ‘I don’t like my assessments. It’s too high.’ (Then the board says) ‘Why do you think it’s too high?’ ‘It’s just too high,’” Donahue said. “That’s not an argument. That doesn’t provide us with enough information to consider your case.”

“You have to come in with legitimate facts and figures, data that gives us the opportunity to compare that with what the city assessor’s office has done….(Appellants) need to almost hyper-focus on their location and reach out in the geographic area around them to find the anomalies that may help their case.”

Virginia law requires that localities regularly assess the real estate in their jurisdiction, and it references standards established by the International Association of Assessment Officers, guidelines that McKeithen, the city assessor, said his department follows.

But there’s not much in the code that dictates assessment methodologies; i.e., whether to use cost-based, sales comparison or income approaches. Smith sees that as a problem.

“There is no real estate tax assessment code in Virginia,” he said. “There is a statute that requires localities to assess real estate in accordance with generally accepted appraisal practices, procedures, rules and standards. But there’s not any real statutory framework that defines what that means, and so what happens on a practical basis is you could have 140-some-odd different assessors or commissioners of the revenue in Virginia who do things differently. So there’s a real lack of consistency across the commonwealth.”

Smith said there needs to be a statewide commitment to assessing properties as accurately as possible, but that he doesn’t believe there’s much political willpower to change the code to do that.

“I’ll sum it up to say, in my opinion, there are more areas of deep concern than there are areas of deep relief by an order of several magnitudes,” Smith said of modern assessing in Virginia.

“I respect that it’s difficult sometimes to find the right people or to retain the best help once you have it. But those aren’t legitimate excuses. This is a position of public trust in my mind. You’re taking money out of people’s pockets, you’re the person determining what their property tax bill is. And you have an obligation to do it right. No matter how hard it is.”

Donahue said it’s a tall task for the city to accurately reassess each property every single year, and that even with time-saving tools like mass appraisal software, assessors inevitably trail the market.

“Every property is unique and the assessor’s office does not have the time, manpower or ability to physically look at every property to reassess. It’s impossible,” Donahue said. “But I think that department and the people that are in there do a good job.”

I’ve had similar issues. The office reassessment process used to be far more reasonable, they were amenable to mathematical and legal arguments. Something has changed. I get the feeling there is an administrative diktat in the office that all appeals are to be treated very harshly. The only one I have won recently was an uninhabitable building project that was assessed as a finished house. And that took a surprising amount of work. Things used to be assessed at a consistent 80-90% of market value. Now it’s a consistent 105%, which is a hill not worth dying on. I really… Read more »

That’s likely.

When I lived in Albany, they would politely review all appeals and then say no, and, unlike VA, there were no laws to protect you from over assessments. My father, a lifelong Democrat when voting in Federal elections, told me I should officially register as a Democrat because certain cities were notoriously politically corrupt and punitive.

Certain cities, meaning Albany. I am from Albany as well.

I worked for state government in Albany during the Pataki to Cuomo years. sheesh

We’re everywhere down here. Had dinner with a couple from Binghamton just a few days ago…

Virginia law requires that assessments be 100% of market value. The assessor has a fiduciary responsibility of estimating fair market value, although most skew a little on the low side of what is a reasonable opinion just so they don’t have to fight off thousands of appeals every year. The chart in the article which shows less than a 0.007% appeal rate (even filed, not necessarily approved) bears this out. The old post office example shows how tricky some of the 72,000 parcels can be. The assessor has an obligation to value the property based on how much it could… Read more »

It’s also a state law that the tax rate be lowered periodically to balance the increase in the assessments. The City ignores that obligation. The city tax revenues have increased about $40 M + per year the last three years. There’s no revenue problem; there’s a spending problem!

The Virginia Code does not require that the tax rate be lowered when assessments and revenue increase. The Virginia Code requires that in certain circumstances the locality follow a public notice and hearing procedure separate from that required for setting the tax rate.

https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title58.1/chapter32/section58.1-3321/

Which the city never does! They simply take a vote on the tax rate toward the end of a November city council meeting each year. Usually there is no one around at 11 pm to argue for a tax rate reduction.

yes. As I said that’s how it used to work. Not how it works anymore though. The change has been noticeable.

And I agree with you on the tax raise and city council of course. The tax rate is, by state law, supposed to go down as the assessments go up.

The city council overrides that every year, which is an under the table tax hike that gets far too little publicity

That’s our fault as citizens. Meanwhile, we have all sorts of loud people who cause disorder over things our local govt has no control over.

There’s a simple solution here that would fix all – City Council must lower the tax rates on assessed values! They’ve been TALKING about it forever, but talk is cheap. DO something about it!

Good luck! Last year they voted to keep the same rate with one council member from South Richmond publicly stating that the people who voted against the casino could afford to pay $1.20 per $100.

Banditry.

The value of a property is subjective, what is not is the $1.20 per $100 per assessed value. The obvious solution would be to lower the tax rate to compensate for the higher real estate assessments, but the City Council refuses to do so. They say they need our money for this or that. There is never going to be enough of somebody else’s money to spend until we elect a Council that will lower the rate and rein in spending. This also starts with the developers themselves who rely on city subsidies to help fund their projects, such as… Read more »

Well, people obviously need to consider voting differently. Things always get bad in one-party localities and countries — the government gets too arrogant and the stupidities get unchecked and uncorrected until revolution occurs when it is at a country level, at a local level people just vote with their feet and the badly run places get ever worse and become cautionary tales of one kind or another. The South, esp places like Mississippi, used to be a great example of this, but these days it tends to more be places like Chicago, Baltimore — and increasingly it is California and… Read more »

I didn’t see any mention of the supplemental bills/cash grab here. That’s an even more infuriating aspect of this, imo

It’s unlikely that assessments will drop precipitously and the effect is to chase businesses and those on fixed incomes out of the city. The answer is to do what the law requires and drop the tax rate, in this case about 20%. Legends owner Tom Martin told me that his tax bill has more than doubled in the last five years, making it difficult for him to stay in business. But the value of his land far exceeds the value of the improvements, if not what it was just two years ago. My neighbors are stressed about the increases in… Read more »

Maybe you should consider giving the Mayor his due.

The best mayors do things like do more with less money, and then lower taxes, which brings in more talented and energetic people — a virtuous cycle.

Richmond mostly benefits from the mismanagement of other places, but increasingly people are choosing places like NC.

The Richmond mayor doesn’t lower tax rates. City council does.

True with an asterisk. He/she proposes the budget and drives the conversation. Stony at one point tried to raise the rate, at another proposed lowering it if the casino was approved, and won a one-time rebate. You can’t give the mayor a pass on one of the most fundamental aspects of leadership.

Yes — I read an article this morning that he has decided to run for Lt Governor — partly because he believes in “tax fairness” — I think he means raising taxes.

I agree with all the comments. As a small time investor the City is forcing us out of the market. While over in Henrico they are lowering tax rates. Fiscal Responsibility!!! the City is NOT accountable to anyone.

Richmond proper is not growing AT ALL for several years now, while central Virginia has the highest growth in the State. Biggest absolute growth: Chesterfield, biggest % growth: New Kent and, interestingly, biggest recent real estate value rise……. Oilville???

The city IS accountable to the voters, but the voters have been distracted by a bunch of tilting at windmills pie in the sky issues that can’t be solved at the local level, esp by the measures that the political leadership says they can — Richmond Public Schools were supposed to improve — DID THEY???

The City’s population is growing steadily. Its at approximately 230,000 now, about 30,000 above the year 2000 and is projected to hit 250,000 in the next 10 years.

That was true until 2020.

I was surprised too.

Check out Cardinal News for all the details — CHESTERFIELD has been growing by leaps and bounds since 2020, but Richmond has remained flat.

https://cardinalnews.org/2024/02/21/some-counties-in-southwest-virginia-have-seeing-a-big-influx-of-newcomers-others-arent/

2020 census was clearly not accurate for Richmond, just as it wasn’t in similar places for the same reasons.

Easy to look at things which show this, like the vacancy rate in new multifamily

What are you saying? That Bruce is wrong somehow or I am wrong somehow.

To the best of my knowledge the census was accurate but if you have a link I will look at it.

But I am talking about 2020 to now. Richmond’s population has been flat, but Chesterfield’s and some ex-urbs have soared in population. Even Petersburg grew faster than Richmond during that time.

Do Richmond Public Schools still teach Virginia History? Take school trips to St. Johns Church, Capitol Square, Monticello, Mount Vernon, Williamsburg and Washington,D.C.? These places we visited on elementary school-class trips that I still remember all these years later. The citizens of Richmond today vote as if they enjoy living in a socialist nightmare until the price goes up. I don’t blame the people for their choices as they are easily influenced, sometimes intimidated, to try and fit in with what’s constantly being fed to them by influencers and pop culture.

Well, they do…..

History is a battleground — we never taught a balanced history, and now the balance has gone to another unbalanced teaching….

I don’t mean to question history. If I was taught history one way and you another way, how do we find a common ground? So by definition then revisionist history is meant to divide a society. Or to change how history is taught is to change how we vote. If I was taught Columbus discovered America but now people are taught Columbus destroyed America where does that get us? Do we just believe different truths and call one another idiots? lol.

…I mean, Leif Erickson discovered America long before Columbus, regardless of your opinion of Columbus.

Broader point: history isn’t really fixed. Sure, people reframe things for political reasons – and probably shouldn’t – but disregarding that, research and debate are always ongoing. Thinking of history in terms of fixed truths – especially with regards to interpreting meaning, intent, or significance – is a simplification if not a mistake.

Thanks. You explain that well with clarity. During the take down of the Statues in Richmond some of the points you make were discussed then, but fell on deaf ears of the crazed mobs. I was disappointed to see the Columbus Statue tossed into the Boat Lake. Monument Ave. is no longer a tourist/learning attraction. I drove down that street the other day and it now just blends in as any other street with no significance other than expensive homes which are as common as inexpensive homes. Of course, some history is fixed truth, such as Neil Armstrong being the… Read more »

These people are just psychos with a moralistic sounding excuse to act badly, harass and intimidate and not be punished for it by legal means.

Code of Virginia 58.1-3201, states, “All general reassessments or annual assessments in those localities which have annual assessments of real estate, except as otherwise provided in § 58.1-2604 (public service corporations), shall be made at 100 percent fair market value ….” This goes against the city assessor’s statement of assessing properties at “highest and best use” which is normally reserved for property appraisals and not assessments.

Sounds like a lawsuit of some kind is in order.