Thalhimer Realty Partners is building a new seven-story apartment building on the western side of Arthur Ashe Boulevard, while also planning the multibillion-dollar Diamond District redevelopment to replace The Diamond, pictured right. (Mike Platania photos)

Richmond’s bustling development scene is facing the most formidable foe it has seen in recent years: rising interest rates.

The spike in loan rates that began in 2022 has prompted some real estate developers to rethink their math, leading some to delay construction on previously announced projects in the Richmond region or, in some cases, to put project sites back up for sale.

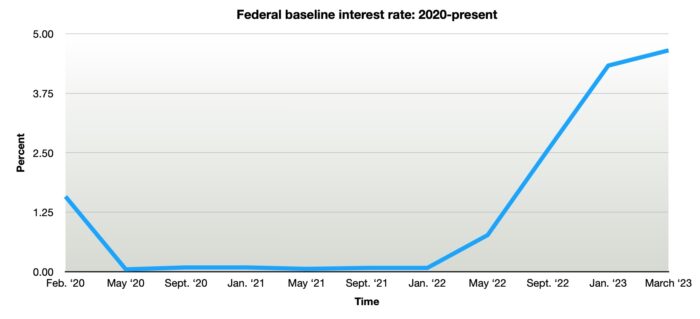

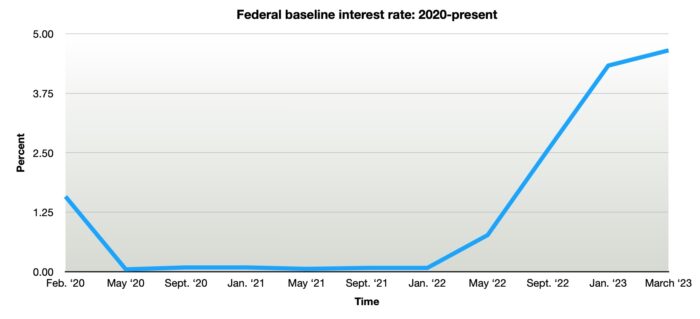

Interest rates had been historically low for more than a decade until last spring when, in the face of rising inflation, the Fed began raising rates at a breakneck pace, thereby increasing the costs to finance new projects.

According to data from the Federal Reserve, its baseline interest rate spent the overwhelming majority of the past 15 years below 1 percent, which allowed developers to typically receive financing from lenders at rates between 3 percent and 5 percent.

As of last month, the Fed had raised the baseline rate for nine months straight, putting it between 4.75 and 5 percent. That means the minimum interest rate many developers are offered by lenders could be nearly 7 percent, in some cases double what they were seeing just a year or two ago.

A graph showing the Federal minimum interest rate from February 2020 to March 2023. (BizSense graphic)

Combined with increased construction costs, the broader economic environment is making it increasingly difficult for developers in the region to plan and build projects. That includes apartment buildings, which have fueled much of the ground-up construction locally in recent years.

Jason Guillot is a principal at Thalhimer Realty Partners, a local firm that has multiple apartment buildings in the queue in Manchester and is actively building in Scott’s Addition. TRP is also part of the RVA Diamond Partners team that’s leading the 67-acre Diamond District redevelopment on Arthur Ashe Boulevard, one of the biggest projects ever planned in the city.

Guillot said inbound migration of residents and businesses into Richmond give the region good fundamentals, but the area can’t escape the macroeconomic environment of high interest rates.

“The current rate and cost environment is undeniably the biggest challenge Richmond’s development and real estate market has faced in recent years,” Guillot said.

He said the rate trend affects developments of all sizes – from an infill townhome project to the $2.4 billion Diamond District redevelopment. And though the sight of cranes and ongoing construction projects around the region may give the impression of business as usual, Guillot said what most don’t see is the lag effect from the recent rise in rates.

“While people may question the real effect of these rate increases as they continue to see cranes hanging over the city, what they don’t realize is that those projects were funded prior to the change in the market,” Guillot said.

‘Prices are just out of control’

A rendering of the 12-story SNP building that was planned to rise on a Jackson Ward parking lot and is now back on the market. (Courtesy Northmarq)

Andy Little, a principal at John B. Levy & Co., a local investment banking firm that helps developers assemble their capital sources for projects, said that because of the change in interest rates, an apartment building that would have cost $50 million to build in 2020 might now cost around $70 million.

“I think you could get things built in 2020 for probably $200,000 per unit,” Little said. “I’d say today that’s more like $275,000 per unit.”

With that cost factor looming, some developers have looked to unload certain projects by listing for sale both the land and approved plans for new apartment buildings in the city.

Bonaventure, a Northern Virginia-based developer, is trying to sell a 1.7-acre site and approved plans for a 203-unit apartment building in Scott’s Addition after paying $4.45 million for the property in a series of deals from 2020 to 2022. Local development firm SNP Properties put a 1-acre site and corresponding plans for a 12-story apartment tower in Jackson Ward on the market in March. It paid $6.1 million for that site in September, a sale that was the highest per-acre tag the neighborhood’s seen.

Other developers, both small and large, are delaying projects while hoping costs come down.

Shakil Siddiqui runs Maryland-based Haris Design & Construction. Since 2020 he’s been planning his entrance into the Richmond market with a pair of apartment buildings totaling 110 units along Hull Street in Manchester, including on the former Lighthouse Diner site at 1228 Hull St.

Though he owns both plots and has razed the old Lighthouse structure, Siddiqui has yet to begin construction and says he will continue to wait for much of 2023.

The site of the former Lighthouse Diner in Manchester. A five-story apartment building is planned to rise on the site.

“We’re thinking of starting construction toward the end of the year, but right now prices are just out of control,” Siddiqui said. “It’s not the construction costs, it’s the interest rates.”

Zimmer Development Co., a large North Carolina-based firm that’s planning the massive, multi-phase Fulton Yard project near Rocketts Landing that’s slated to eventually bring over 500 apartments and 100,000 square feet of commercial space, is similarly in a holding pattern.

Zimmer, whose portfolio counts $3 billion in developed assets, won the county’s approval for Fulton Yard in 2019, spent $5.3 million on the 23-acre project site in 2020 and was planning to break ground on it in 2022. But project manager Landon Zimmer said the firm is not in a rush to build in the current environment.

“The way we look at it is, we’re kind of getting paid to wait. We’re not getting rent on it, but the value of the property is going up faster than inflation, we think, and development around us is being developed,” Zimmer said.

“Despite saying that, we’d like to get started on construction this year,” he added, noting that the developer has a contractor lined up and ready to go when the time is right.

Level 2 Development out of Washington, D.C., is planning a pair of sizable projects on and around North Arthur Ashe Boulevard. Its 305-unit Leigh Addition would replace a number of aging buildings on the east side of the boulevard, and the firm is also planning a 375-unit apartment building on land it bought last year next to Movieland At Boulevard Square.

Level 2 principal David Franco said the developer has been aiming to begin construction on Leigh Addition in May and the Movieland-adjacent project a few months later, but that it’s been tricky to get the numbers to work out.

“It definitely has been challenging, but we’re working through those challenges and we’re optimistic,” Franco said. “We think construction costs have leveled off and so, barring some surprise, we think we’ll move forward with the projects.”

‘Come to the table with cash’

The process of moving forward on projects, however, has become more expensive out of the gate. With interest rates high, lenders now are asking for more up-front cash from developers – similar to demanding a higher down payment from people trying to buy houses.

Some developers can make up the difference by raising more equity from private investors or through loans from state institutions such as Virginia Housing, but many simply need to fork over more cash.

Little, the principal at John B. Levy & Co., said that when interest rates were low, it wasn’t unusual for developers to get a loan for 75 to 80 percent of the total cost of their project from a bank.

“They’re now looking at 60 to 65 percent,” Little said. “If you’re looking at large projects and they get to be very large checks, most developers don’t want to put all their cash into development deals. They’re now having to come to the table with cash in order to get deals built.”

Developers of new construction projects deal with interest rates on multiple fronts. Several types of loans with varying purposes, lengths and repayment strategies are often needed to see a project through to the end.

Some developers begin a project with bridge loans, which are typically shorter-term loans used to buy real estate. Once a developer has the land or building it needs for a project, a bridge loan can be paid off by being refinanced into a new-construction loan, which provides a developer funding for the actual construction of the building.

Upon the building’s completion, new-construction loans are often paid off by the developer either selling the new building or refinancing the loan into a long-term or “permanent” loan.

Adding to the complexity are the recent collapses of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, which Little said are making lenders even more risk-averse.

“We think this could impact the way lenders look at deals, particularly when the White House is saying that we need to beef up regulation on banks to stop this from happening again,” Little said of the added tumult in banking. “The uncertainty with regard to how banking regulators will act will tend to decrease their risk appetite.”

Guillot at Thalhimer said the Federal Reserve’s rate increases have prompted lenders of all sizes to slow the flow of the money spigot as they manage withdrawals and other risks caused by the SVB and Signature sagas.

“The only way out is to fund deals with two to three times more equity, which results in more heavily concentrated equity positions in fewer projects,” Guillot said.

It isn’t only Richmond where it’s become more difficult to get loans. Franco at Level 2 said he’s seen interest rates slowing construction all over the country, and Zimmer Development said Fulton Yard is one of multiple projects nationally on which it’s tapping the brakes.

“Anywhere, like in Richmond, where we haven’t really broken ground or are under construction yet, we’re waiting,” said Adam Tucker, Zimmer’s vice president. “If there hasn’t been a shovel in the ground, we’re going to sit tight for a little bit.”

Volatile markets tend to lead real estate investors back to focus on larger cities, Little said, but he added that no market is immune from the current slowdown.

“I don’t think any market is attracting a lot of capital for ground-up construction,” Little said. “Richmond was really on a nice tear, getting on the radar screen of a lot of big investment groups. I hope that momentum continues, but it’s difficult everywhere to get things built.”

‘We have a math problem we’re solving’

Outside of the Federal Reserve lowering rates, there are two main ways for the impacts of high interest rates to be remedied: construction costs coming down, or apartment rents going up.

Guillot said that after skyrocketing during the early days of the pandemic, construction costs have plateaued but have not come down.

Little said it’s rare to see costs come down, leaving rent increases as the most likely avenue for mitigating interest rate rises. And he said he doesn’t see rents decreasing in the near term, particularly if high interest rates slow down the construction and supply of new apartments and demand remains high.

“If we’re in an inflationary environment for the next couple of years, all that extra (apartment) supply is going to work its way through the system, then it’s going to be tight again for those that are seeking apartments,” Little said.

Little said he sees the current economic landscape as unique, something much different from the Great Recession in 2008 when lenders didn’t have money to lend. These days, he said, plenty of money is out there; it’s just seen as too expensive in the eyes of the developers that pursue it.

“We’re in a weird environment…where it’s difficult to get deals done, even though money is readily available,” Little said. “The industry has to adjust to higher rates, and it will. I don’t have a crystal ball, but I think people will adjust faster than we suspect.”

Guillot agrees with that optimistic long-view, even for a complex multi-phase project such as the Diamond District. That’s despite a public statement this week from Lou DiBella, president of the Richmond Flying Squirrels, who questioned in a statement to the Times-Dispatch whether the Diamond District’s new anchor baseball stadium can be brought to fruition in time for a Major League Baseball-mandated 2025 deadline.

Guillot said changing interest rates have complicated the financing of the Diamond District and are contributing to the delays lamented by DiBella, but added that they haven’t made such a project impossible.

“We have a math problem we’re solving and clearly it became more tricky when the Fed hiked interest rates at an unprecedented pace,” Guillot said. “But our goal all along has been to ensure that we have a responsible financial plan in place that meets the city’s long-term goals and objectives.”

He said RVA Diamond Partners has been working “around the clock” on the Diamond District with representatives from the City of Richmond, the Flying Squirrels, VCU and other parties.

“We are confident in our development plan and, with the city as our partner, are committed to building an outstanding new ballpark for the Flying Squirrels and VCU that anchors a sustainably built neighborhood with a public park and affordable housing, and all of the other exciting amenities that Richmonders have been anticipating,” he said.

Even while navigating a high-pressure deal like the Diamond District planning process, Guillot said he thinks Richmond is “unequivocally in a sustained growth pattern for years to come,” and that he’s optimistic interest rates will be a short-term problem.

“In the long term we should all be very bullish about our region as more businesses and people make Richmond their home,” Guillot said. “Even the Fed can’t slow down Richmond.”

Thalhimer Realty Partners is building a new seven-story apartment building on the western side of Arthur Ashe Boulevard, while also planning the multibillion-dollar Diamond District redevelopment to replace The Diamond, pictured right. (Mike Platania photos)

Richmond’s bustling development scene is facing the most formidable foe it has seen in recent years: rising interest rates.

The spike in loan rates that began in 2022 has prompted some real estate developers to rethink their math, leading some to delay construction on previously announced projects in the Richmond region or, in some cases, to put project sites back up for sale.

Interest rates had been historically low for more than a decade until last spring when, in the face of rising inflation, the Fed began raising rates at a breakneck pace, thereby increasing the costs to finance new projects.

According to data from the Federal Reserve, its baseline interest rate spent the overwhelming majority of the past 15 years below 1 percent, which allowed developers to typically receive financing from lenders at rates between 3 percent and 5 percent.

As of last month, the Fed had raised the baseline rate for nine months straight, putting it between 4.75 and 5 percent. That means the minimum interest rate many developers are offered by lenders could be nearly 7 percent, in some cases double what they were seeing just a year or two ago.

A graph showing the Federal minimum interest rate from February 2020 to March 2023. (BizSense graphic)

Combined with increased construction costs, the broader economic environment is making it increasingly difficult for developers in the region to plan and build projects. That includes apartment buildings, which have fueled much of the ground-up construction locally in recent years.

Jason Guillot is a principal at Thalhimer Realty Partners, a local firm that has multiple apartment buildings in the queue in Manchester and is actively building in Scott’s Addition. TRP is also part of the RVA Diamond Partners team that’s leading the 67-acre Diamond District redevelopment on Arthur Ashe Boulevard, one of the biggest projects ever planned in the city.

Guillot said inbound migration of residents and businesses into Richmond give the region good fundamentals, but the area can’t escape the macroeconomic environment of high interest rates.

“The current rate and cost environment is undeniably the biggest challenge Richmond’s development and real estate market has faced in recent years,” Guillot said.

He said the rate trend affects developments of all sizes – from an infill townhome project to the $2.4 billion Diamond District redevelopment. And though the sight of cranes and ongoing construction projects around the region may give the impression of business as usual, Guillot said what most don’t see is the lag effect from the recent rise in rates.

“While people may question the real effect of these rate increases as they continue to see cranes hanging over the city, what they don’t realize is that those projects were funded prior to the change in the market,” Guillot said.

‘Prices are just out of control’

A rendering of the 12-story SNP building that was planned to rise on a Jackson Ward parking lot and is now back on the market. (Courtesy Northmarq)

Andy Little, a principal at John B. Levy & Co., a local investment banking firm that helps developers assemble their capital sources for projects, said that because of the change in interest rates, an apartment building that would have cost $50 million to build in 2020 might now cost around $70 million.

“I think you could get things built in 2020 for probably $200,000 per unit,” Little said. “I’d say today that’s more like $275,000 per unit.”

With that cost factor looming, some developers have looked to unload certain projects by listing for sale both the land and approved plans for new apartment buildings in the city.

Bonaventure, a Northern Virginia-based developer, is trying to sell a 1.7-acre site and approved plans for a 203-unit apartment building in Scott’s Addition after paying $4.45 million for the property in a series of deals from 2020 to 2022. Local development firm SNP Properties put a 1-acre site and corresponding plans for a 12-story apartment tower in Jackson Ward on the market in March. It paid $6.1 million for that site in September, a sale that was the highest per-acre tag the neighborhood’s seen.

Other developers, both small and large, are delaying projects while hoping costs come down.

Shakil Siddiqui runs Maryland-based Haris Design & Construction. Since 2020 he’s been planning his entrance into the Richmond market with a pair of apartment buildings totaling 110 units along Hull Street in Manchester, including on the former Lighthouse Diner site at 1228 Hull St.

Though he owns both plots and has razed the old Lighthouse structure, Siddiqui has yet to begin construction and says he will continue to wait for much of 2023.

The site of the former Lighthouse Diner in Manchester. A five-story apartment building is planned to rise on the site.

“We’re thinking of starting construction toward the end of the year, but right now prices are just out of control,” Siddiqui said. “It’s not the construction costs, it’s the interest rates.”

Zimmer Development Co., a large North Carolina-based firm that’s planning the massive, multi-phase Fulton Yard project near Rocketts Landing that’s slated to eventually bring over 500 apartments and 100,000 square feet of commercial space, is similarly in a holding pattern.

Zimmer, whose portfolio counts $3 billion in developed assets, won the county’s approval for Fulton Yard in 2019, spent $5.3 million on the 23-acre project site in 2020 and was planning to break ground on it in 2022. But project manager Landon Zimmer said the firm is not in a rush to build in the current environment.

“The way we look at it is, we’re kind of getting paid to wait. We’re not getting rent on it, but the value of the property is going up faster than inflation, we think, and development around us is being developed,” Zimmer said.

“Despite saying that, we’d like to get started on construction this year,” he added, noting that the developer has a contractor lined up and ready to go when the time is right.

Level 2 Development out of Washington, D.C., is planning a pair of sizable projects on and around North Arthur Ashe Boulevard. Its 305-unit Leigh Addition would replace a number of aging buildings on the east side of the boulevard, and the firm is also planning a 375-unit apartment building on land it bought last year next to Movieland At Boulevard Square.

Level 2 principal David Franco said the developer has been aiming to begin construction on Leigh Addition in May and the Movieland-adjacent project a few months later, but that it’s been tricky to get the numbers to work out.

“It definitely has been challenging, but we’re working through those challenges and we’re optimistic,” Franco said. “We think construction costs have leveled off and so, barring some surprise, we think we’ll move forward with the projects.”

‘Come to the table with cash’

The process of moving forward on projects, however, has become more expensive out of the gate. With interest rates high, lenders now are asking for more up-front cash from developers – similar to demanding a higher down payment from people trying to buy houses.

Some developers can make up the difference by raising more equity from private investors or through loans from state institutions such as Virginia Housing, but many simply need to fork over more cash.

Little, the principal at John B. Levy & Co., said that when interest rates were low, it wasn’t unusual for developers to get a loan for 75 to 80 percent of the total cost of their project from a bank.

“They’re now looking at 60 to 65 percent,” Little said. “If you’re looking at large projects and they get to be very large checks, most developers don’t want to put all their cash into development deals. They’re now having to come to the table with cash in order to get deals built.”

Developers of new construction projects deal with interest rates on multiple fronts. Several types of loans with varying purposes, lengths and repayment strategies are often needed to see a project through to the end.

Some developers begin a project with bridge loans, which are typically shorter-term loans used to buy real estate. Once a developer has the land or building it needs for a project, a bridge loan can be paid off by being refinanced into a new-construction loan, which provides a developer funding for the actual construction of the building.

Upon the building’s completion, new-construction loans are often paid off by the developer either selling the new building or refinancing the loan into a long-term or “permanent” loan.

Adding to the complexity are the recent collapses of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, which Little said are making lenders even more risk-averse.

“We think this could impact the way lenders look at deals, particularly when the White House is saying that we need to beef up regulation on banks to stop this from happening again,” Little said of the added tumult in banking. “The uncertainty with regard to how banking regulators will act will tend to decrease their risk appetite.”

Guillot at Thalhimer said the Federal Reserve’s rate increases have prompted lenders of all sizes to slow the flow of the money spigot as they manage withdrawals and other risks caused by the SVB and Signature sagas.

“The only way out is to fund deals with two to three times more equity, which results in more heavily concentrated equity positions in fewer projects,” Guillot said.

It isn’t only Richmond where it’s become more difficult to get loans. Franco at Level 2 said he’s seen interest rates slowing construction all over the country, and Zimmer Development said Fulton Yard is one of multiple projects nationally on which it’s tapping the brakes.

“Anywhere, like in Richmond, where we haven’t really broken ground or are under construction yet, we’re waiting,” said Adam Tucker, Zimmer’s vice president. “If there hasn’t been a shovel in the ground, we’re going to sit tight for a little bit.”

Volatile markets tend to lead real estate investors back to focus on larger cities, Little said, but he added that no market is immune from the current slowdown.

“I don’t think any market is attracting a lot of capital for ground-up construction,” Little said. “Richmond was really on a nice tear, getting on the radar screen of a lot of big investment groups. I hope that momentum continues, but it’s difficult everywhere to get things built.”

‘We have a math problem we’re solving’

Outside of the Federal Reserve lowering rates, there are two main ways for the impacts of high interest rates to be remedied: construction costs coming down, or apartment rents going up.

Guillot said that after skyrocketing during the early days of the pandemic, construction costs have plateaued but have not come down.

Little said it’s rare to see costs come down, leaving rent increases as the most likely avenue for mitigating interest rate rises. And he said he doesn’t see rents decreasing in the near term, particularly if high interest rates slow down the construction and supply of new apartments and demand remains high.

“If we’re in an inflationary environment for the next couple of years, all that extra (apartment) supply is going to work its way through the system, then it’s going to be tight again for those that are seeking apartments,” Little said.

Little said he sees the current economic landscape as unique, something much different from the Great Recession in 2008 when lenders didn’t have money to lend. These days, he said, plenty of money is out there; it’s just seen as too expensive in the eyes of the developers that pursue it.

“We’re in a weird environment…where it’s difficult to get deals done, even though money is readily available,” Little said. “The industry has to adjust to higher rates, and it will. I don’t have a crystal ball, but I think people will adjust faster than we suspect.”

Guillot agrees with that optimistic long-view, even for a complex multi-phase project such as the Diamond District. That’s despite a public statement this week from Lou DiBella, president of the Richmond Flying Squirrels, who questioned in a statement to the Times-Dispatch whether the Diamond District’s new anchor baseball stadium can be brought to fruition in time for a Major League Baseball-mandated 2025 deadline.

Guillot said changing interest rates have complicated the financing of the Diamond District and are contributing to the delays lamented by DiBella, but added that they haven’t made such a project impossible.

“We have a math problem we’re solving and clearly it became more tricky when the Fed hiked interest rates at an unprecedented pace,” Guillot said. “But our goal all along has been to ensure that we have a responsible financial plan in place that meets the city’s long-term goals and objectives.”

He said RVA Diamond Partners has been working “around the clock” on the Diamond District with representatives from the City of Richmond, the Flying Squirrels, VCU and other parties.

“We are confident in our development plan and, with the city as our partner, are committed to building an outstanding new ballpark for the Flying Squirrels and VCU that anchors a sustainably built neighborhood with a public park and affordable housing, and all of the other exciting amenities that Richmonders have been anticipating,” he said.

Even while navigating a high-pressure deal like the Diamond District planning process, Guillot said he thinks Richmond is “unequivocally in a sustained growth pattern for years to come,” and that he’s optimistic interest rates will be a short-term problem.

“In the long term we should all be very bullish about our region as more businesses and people make Richmond their home,” Guillot said. “Even the Fed can’t slow down Richmond.”

I like Guillots optimism. That young man has made one good move after another since becoming a developer here and he’ll be at the forefront of our market for the next two decades.

Totally agree on him Bruce but I see this as the beginning of the excuse period for why Diamond District fails. Funny, we should be talking about the CDA the city has not yet created (and has NO ordinances before it). The issues with those bonds their interest rates. If the CDA is not created and the bonds not issued why would the developer break ground on the project. Council won’t act without public review and I don’t see them completing their work before after Labor Day, bonds sold by the end of calendar year, and construction starting next February… Read more »

Bye bye Flying Squirrels. Glad we sank another $3mil into Stoney’s newest version of the Coliseum. A blight d shut down fenced off relic that holds lots of memories.

I am starting to see projects that were once a go at the beginning of the year now being postponed. I personally know of 5 ranging from higher education / associated with higher education to mixed use / multifamily – I’m sure there are many others. With banks having liquidity issues, commercial loan issuance being at their lowest point in years if not ever, the terms on commercial loans weighing more on down payment, and continued rate hikes by Step Daddy Powell – we currently have a recipe for disaster; at least in the short term. I hope as the… Read more »

So the solution is more free money? I think not. Developers have been spoiled with instance returns for far too long, not to mention tax credits. Let them take a break on the mass gentrification/uglification of our city. I don’t mind, it’ll keep my property taxes down in the meantime.

The solution is DEFINITELY NOT free money. You’re speaking more mirco while I’m looking at the marco picture. This isn’t just a Richmond problem; I’m seeing it in other areas as well. A balance point needs to be found with rates closer to 2%. The Feds or politicians (both sides) messed up when they decided to keep rates so low for so long after 08′. That plus turning the money printer on during COVID. The other “black swan event” Ukraine / Russia hasn’t helped either. The only solution is to let time play itself out while gradually lowering rates. Hopefully… Read more »

In the past several years the US government has printed a lot of money. This has caused price inflation. In addition, the Federal Reserve has kept interest rates artificially low, and a lot of people assumed it would continue. Our political class is doubling down on its colossal stupidity, giving us never-ending wars, never-ending “government solutions” (which always worsen whatever it is trying to cure), and extraordinary price inflation. And yet we keep voting the same people into office.

Party politics over any progress. That’s how we got Stoney.

Exactly, That’s the point of interest rates. If a project is delayed because the cost of money is rising, then that project was likely not a good use of capital.

SA, this is like your 5th spot-on comment that I have read of yours. you write like you have been following a retired doctor from Texas.

you write like you have been following a retired doctor from Texas.

Kara Swisher has an excellent interview with Larry Summers out this week on her “On” podcast. Agree with your points and he gives a great macro view.